2008 London, and I’m standing outside the George & Dragon (a cultural fixture that sadly got lost in the gentrification that still ensues in London today), with a flat pint in my hand on an unusually warm summers evening. It’s my first weekend back in London, after a long absence and I’m determined to find a new club experience in the city. The big established clubs like Fabric, the Egg and the End were there and always an option, but they would be there later still, and I was hungry for something new and exciting. Literally down the street from the George and Dragon, Plastic People was there too, flexing with the sound of dubstep, and although aware of the genre I had not yet been convinced yet, skeptical of its lo-fi swelling sub-bass and it’s half time rhythms. I was after something a bit more energetic, and a bit more curious on this Friday night, and like a flash, it passed me by on Hackney Road at that very moment.

Walking down the east end high street in broad daylight, a group of early twenty-somethings, dressed like Michael Alig and James st James before the comedown, strode with confidence and swagger. They had the air of people bucking trends and known perceptions their entire life and the street seemed to part ceremoniously at their feet as they took determined strides to their destination. Loud insults flung from open car windows speeding by and shrewd remarks made under breath from passing pedestrians had no effect and carried little weight in their ill-confidence. You knew these kids were cool and shouting insults at them only undermined your own social standing – You would never be as cool as they. I manage to catch up to one of the gang as they traipsed around a corner and find out they’re going to a night called Trailer Trash, where I would later find exactly that which I desired.

Trailer Trash was a sight out of this world. Kids from all manner of backgrounds, packed in like sardines in a old working men’s club, listening to ear-bleeding ghetto tech through broken speakers (I assume broke during the course of that night, and would happen on several occasions again after that night). The sprawl of club kids, music enthusiasts, people just out for a good time and the surreptitious “naked guy” created a colourful and effervescent living diorama that took the essence of club kids in New York in the eighties and made it into something more accessible. Where New York’s club kids would need to work at creating that aura of mystique and drama through planned performances and installations, in the UK these club kids just had a natural disposition for the drama, and just occupying a working men’s club on Friday night transformed the place into some hedonistic den of iniquity and escapism with little more than a DJ, groups of friends… and of course a bit of makeup.

Trailer Trash would eventually lead me to Nuke’em all and DJs like Buster Bennett and Hannah Holland were instrumental figures in creating a scene in London’s east end for a fairly new population of cool twenty-something residents, still making use of the cheap rent and burgeoning night life that started cropping up around Shoreditch. It was a time before the property speculators moved in and established huge loft complexes with pretentious names like Art Nouveau or Avant Garde, filled with clueless stockbrokers and hedge fund capitalists, who desperately longed to be cool by association, but couldn’t hold a candle to those kids from Trailer Trash and Nuke’em all.

Trailer Trash and Nuke’em all were effective rudders for what was cool and constituted as close as you could come to scene, with a mixture of art students and established socialite figures, taking that spirit of nineties New York; the music from present day Chicago; and the ruins of an eighties electronic scene in the east end of London, and morphing it into something completely different. Although it referenced a scene from the past, nothing quite like it had been before it and nothing would follow it, and in that fleeting moment in London for about two years a true club scene existed and would disappear just as soon as it arrived, in the way that any youth scene should. For me this became a testament of nightlife in the UK where they toe their own set of jumbled lines. Techno in the UK never quite sounds like its American forebearers nor did Dubstep sound like anything before it and from the club-kids and their Ghetto Tech soundtrack to the instrumental Grime I’m a big fan of today, there’s always been a unique groove to UK club music.

Although there had been Northern Soul, the working man’s answer to Disco in the north of the UK, in electronic music it would be Acid House, that all arrows point today as the definite character of that UK groove. Not to be mistaken for staunch and specific Chicago sound of Acid House, the UK’s interpretation of the popular trope was a little more irrational and schizophrenic than a 303 walking bassline and a four-four kick and has it’s roots in Ibiza and Balearic. Drug fueled trips to the Spanish island and Amnesia to listen to Alfredo, inspired DJs like Paul Oakenfold, Trevor Fung and Danny Rampling back in the UK. They brought the music (a mix of Chicago House and Balearic Classics), the clothes (careless holidaymaker ensembles) and the drugs (ecstasy) back to the UK for audiences still enamoured with rare groove and ignited a musical and cultural explosion that probably still goes down as the most significant periods in House music.

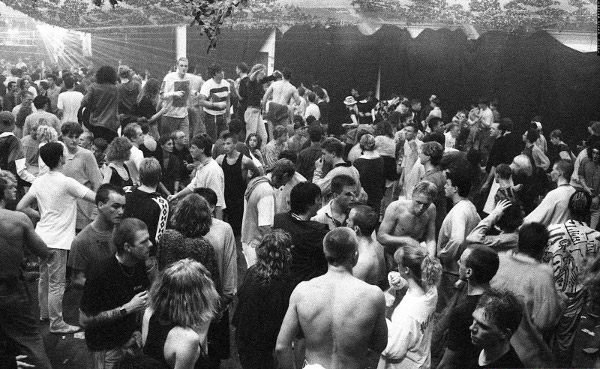

What started out as Balearic, a playful mix of eccentricities, would move almost exclusively into House through clubs like the Haçienda in Manchester and The Trip in London. It swept through the country and brought the music from Chicago and New York to the UK. Where House in the states was a small, exclusive scene, House in the UK reached everybody and anybody. It inspired a cultural youth movement like no one has seen since the hippies, and consequently 1988 became the “second summer of love” and House would be its soundtrack. This new machine music from the states had been wholly and completely accepted in the UK psyche and had completely changed the way people listened to music, danced and even socialised. A continuous, repetitive music encouraged by the drug ecstasy induced trance-like atmospheres for the sole purpose of rhythmical movement and as the crowds grew venues, had to accommodate them and all over the UK tents and sound systems cropped up and rave culture was born.

“Dancing is political, stupid” says Bill Brewster and Frank Boughton in “Last night a DJ saved my life” and for a generation living in the landscape of conservative politics of Margaret Thatcher it became a rebel call that still echoes through the ages. Nowhere since Woodstock in 1969 had there been such a musical roots movement quite like this. Acid House became the battle cry for millions of disenfranchised youths unable to live and work within the orthodox and ancient system they’ve been born into and even if it was just for one night in a muddy field outside the M25, they’d do everything in their power to escape it.

I was only an infant in 1988, but going to a club today and listening to a DJ segue one track into the next in Europe all comes down to what they were doing in the UK in the eighties and the second summer of love. It’s always felt like I was born too late or too early to be part of any significant cultural movement and although the social circumstances in the UK in the eighties would have been anything ideal for a migrant worker like myself, I would have loved nothing more to travel back in time and experience just a moment of that time and place, from which everything concerning European music culture stems. But until the time-travelling delorean stops at my door, I am quite content in the fact that the spirit of UK clubbing lives on every time I am on the dance floor, in the company of others, listening to a DJ soundtrack the night.

One event I was in the right time and place for however was Dubstep. London 2008/9 and I’m at CDR night at plastic people, a Sunday night where a community of music producers, that had met on social forums on the internet, test out new creations through the clubs now legendary sound system. I’m just there as a spectator and the warm bass on the back of my spine is soothing. It’s an unknown track, by an unknown artist, making no real impression on me, but there’s a definite sense of community there that I’d not quite felt before. Although there’d been no escaping Dubstep after Burial’s first album and I had certainly fell for the listening experiences the genre had to offer, clubbing and Dubstep were two completely different things to me at that point. Dubstep with its 140BPM rhythms playing at half time, it’s sluggish rolling bass lines and innovative sonic spectrums had piqued an early interest and tracks from the likes of Untold, Joy Orbison and Kode 9 were interesting developments in electronic music, but reserved for a lazy kind of head-bopping listening experience. It was urban kind of roots music, taking elements from Dub, Reggae, Techno, Drum and Bass and House to make a wholly original style of music, and probably the last truly new genre to crop up in electronic music.

Like UK Garage, Drum n Bass and Bleep that came before it this wasn’t House or Techno as imported from the states, but rather a distinctly UK music with roots in its own urban environment. Featuring some elements like the two step arrangements from UK Garage; the low sinister rumbling bass-lines lifted from the sound system culture that came over with the Jamaican community; and the rapturous tempoes of Drum n Bass, Dubstep was a product of its environment. It was incredibly UK and when the Americans started bastardising the sound of Dubstep, the original purveyors abandoned the style completely and moved into genres like House and Techno taking elements of their music into these genres to create very unique interpretations of these genres. Tracks like Objekt’s Cactus and Joy Orbison’s Hyph Mngo became crossover success stories and consolidated elements from Dubstep into established genres like House and Electro, establishing them as artists today with a penchant for innovative interpretations of club music across genres.

One of the most interesting developments to come from this was instrumental Grime. In 2013 and in the humid oversaturated world of Deep House’s most prominent year, Instrumental Grime would arrive in the subterranean depth of London with a sinister snarl. It would be Logos and his debut album Cold Mission that would win me over to the dark side where acts like Pinch, Mumdance and Randomer dwelled. Percussive and minimal instrumental Grime took Grime’s dark and menacing attitude and combined it with machines from the palette of Techno and House to create an entire style of music onto its own. Instrumental grime continues to put forward some of the more interesting and completely unusual progressions on the dance floor in a way only the UK could. They defy barriers and spin a thread through all of electronic music with specific pressure points in UK music culture. It will undoubtedly never be quite as popular as Acid House in the eighties, but there’s a crossover potential certainly if collaborations like those between Mumdance and young Grime MC Novelists keep happening.

Theirs is the latest chapter and the future in the UK’s ongoing traditions and lack thereof in club music. They continue to pursue club music as this flexible, amorphous entity that pick and chooses across genres, influences and social movements to consolidate a UK sound and attitude. Even though I’ve merely picked through a mere handful of chapters and details in UK music, the results are congruous between them. Defying characterisation, but with something similar running through it, clubbing in the UK is and always will be an anomaly, an significant one at that.