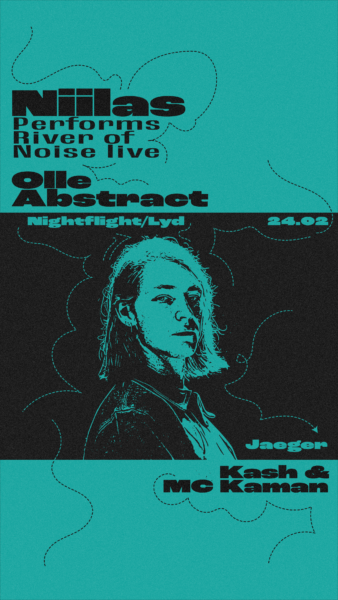

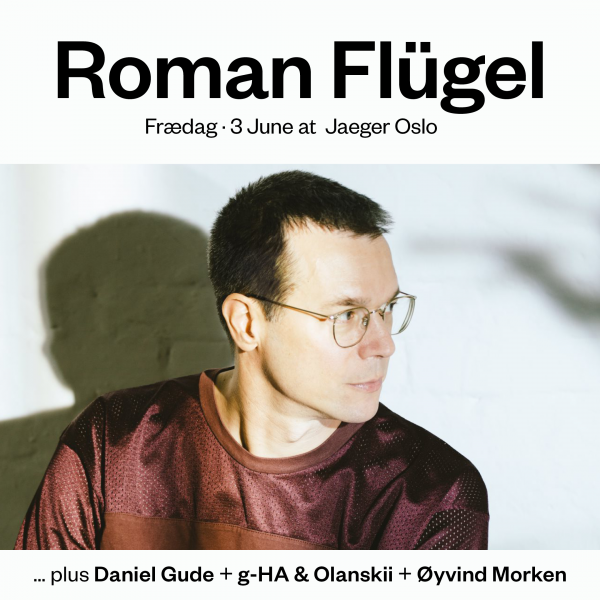

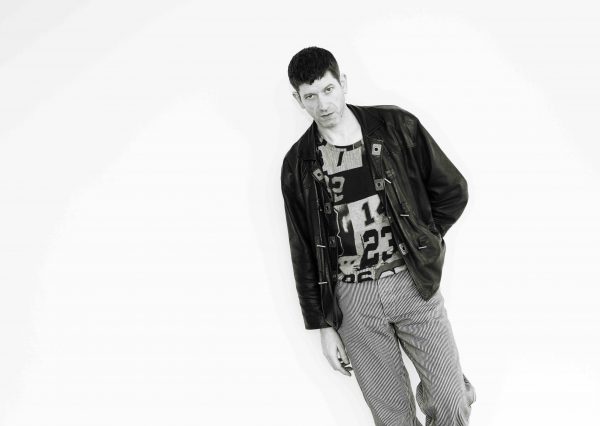

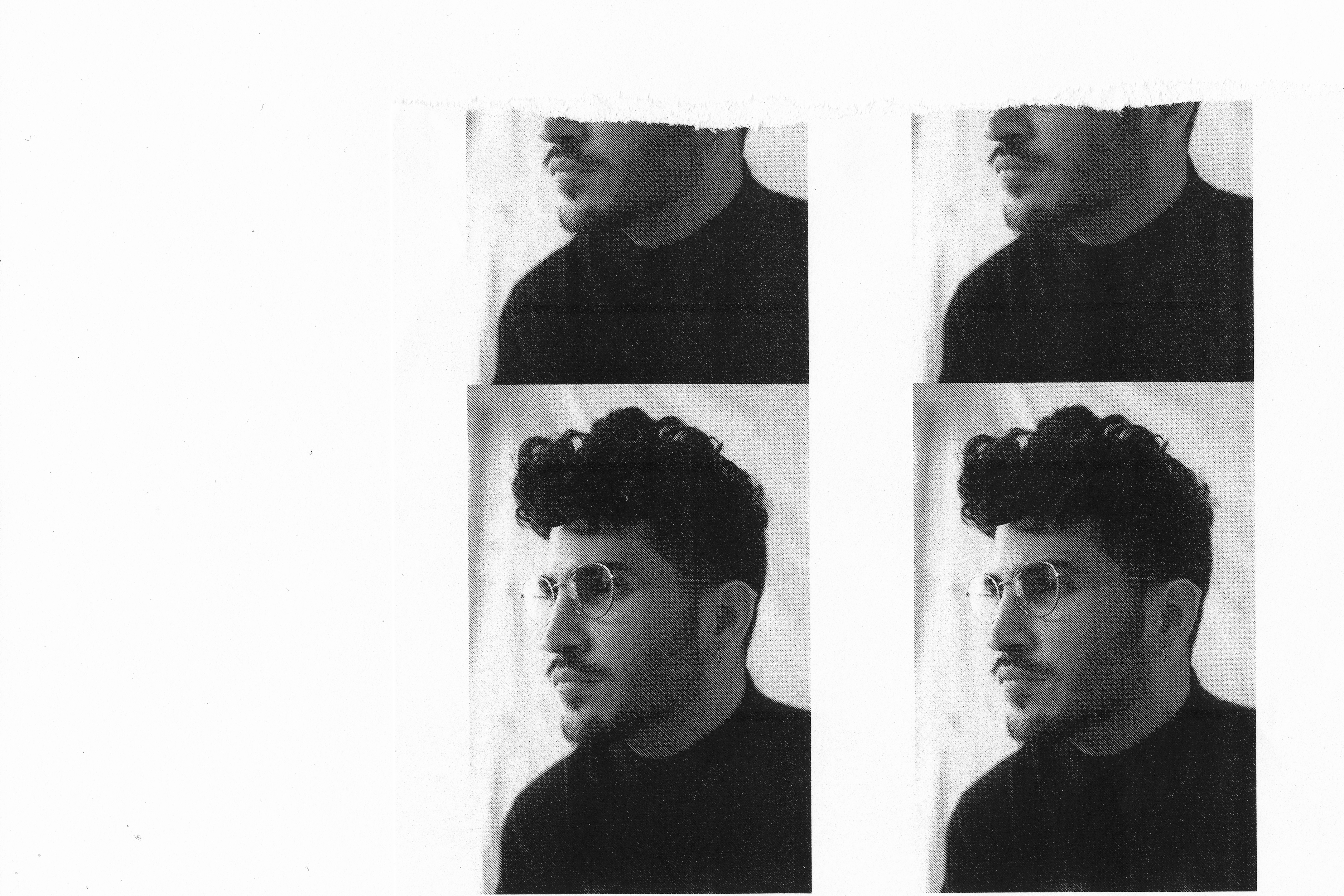

We caught up with Why Kai ahead of their LP launch at Jaeger to talk about their debut album and the history of the project

Jazz and electronic music have been curious bedfellows in Norway. Artists like Bugge Wesseltoft, Nils Petter Molvæar and more recently Hilde Marie Holsen and Stain Balducci, have been exploring the borders of these genres. It has developed a rich history in the confluence of musical styles in the region in a way that is very uniquely Norwegian.

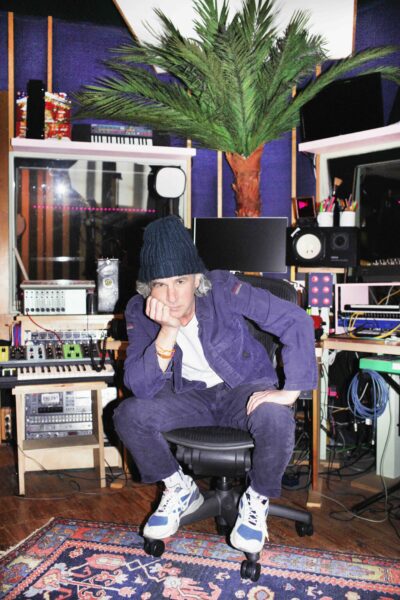

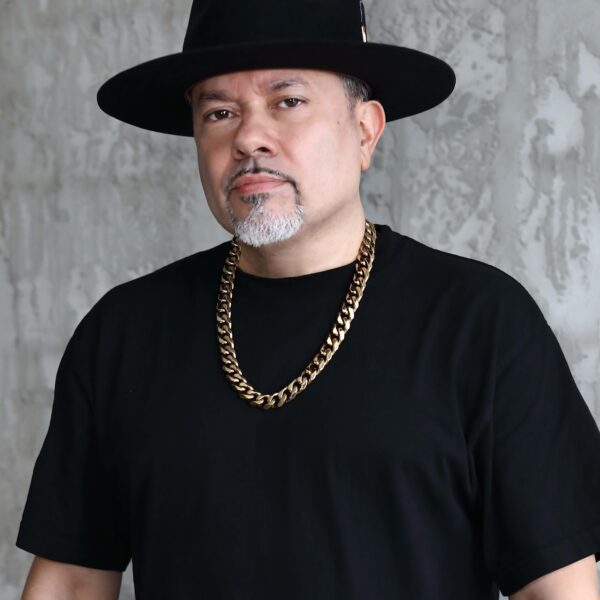

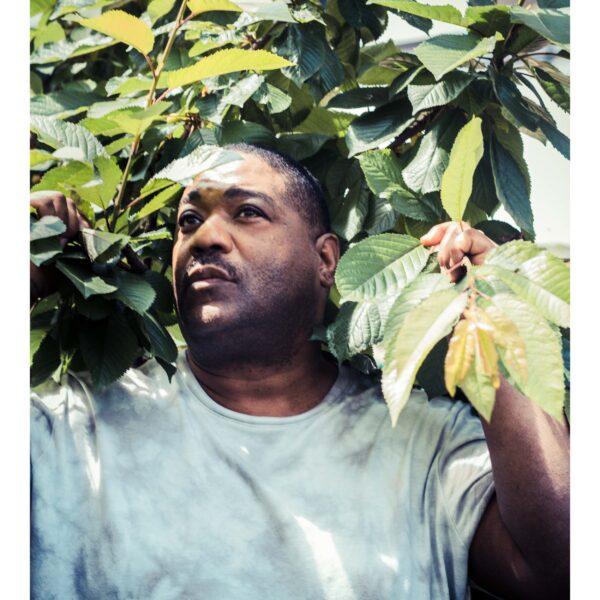

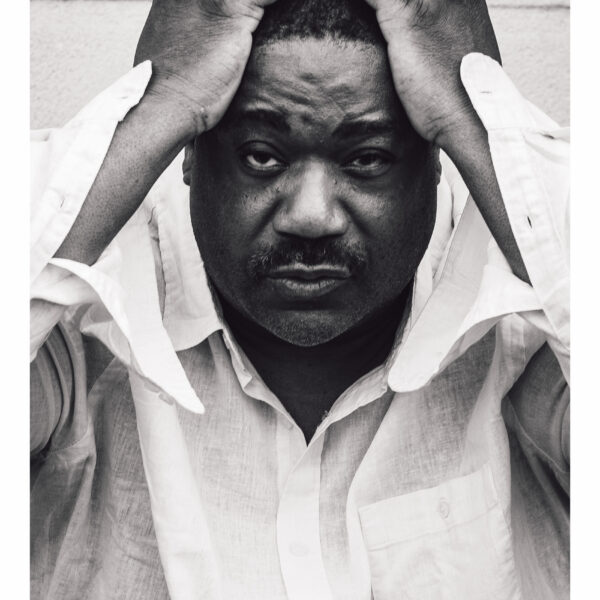

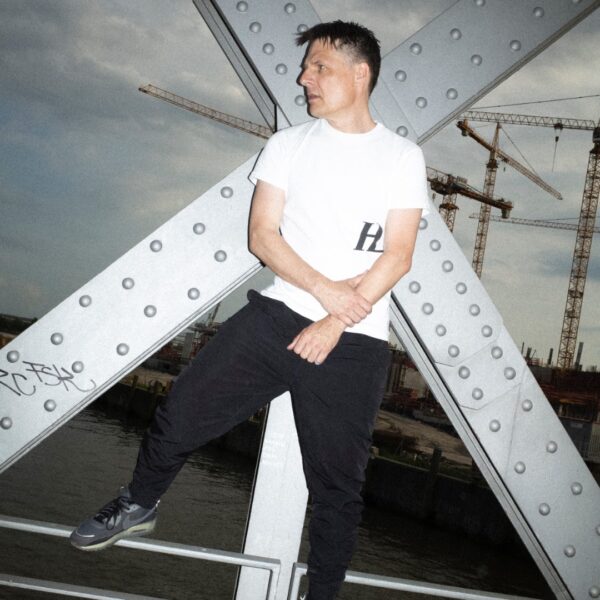

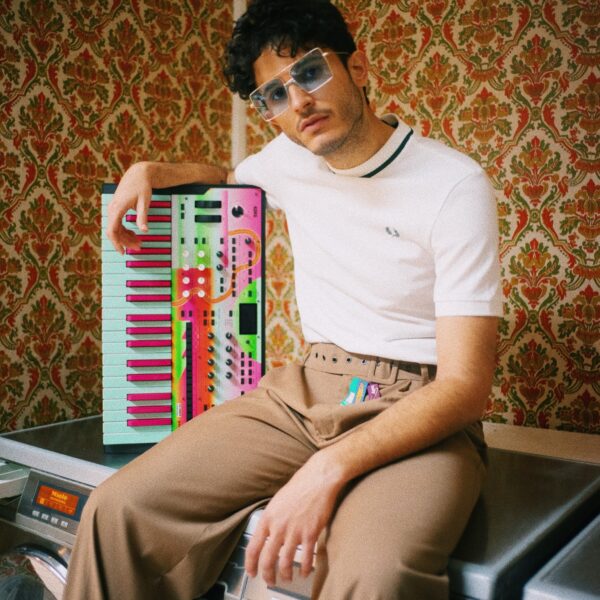

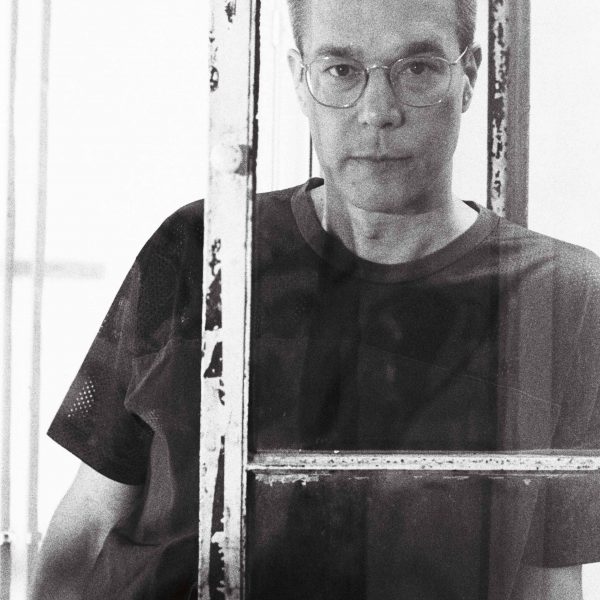

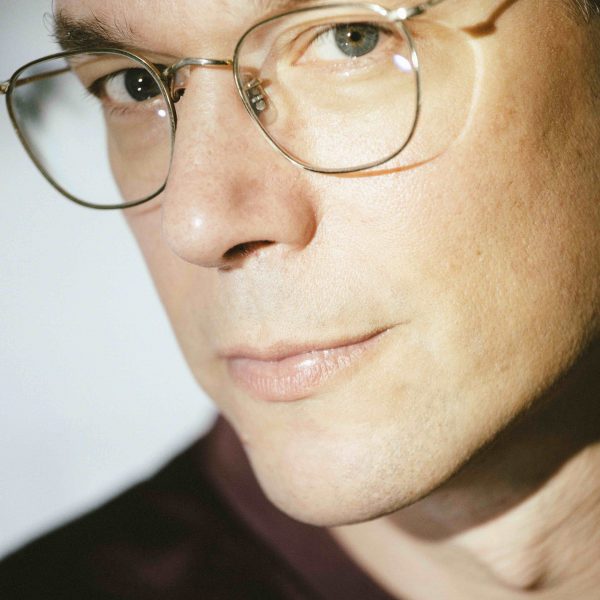

The latest addition to this legacy has been Why Kai, the solo project of session pianist, Jazz musician and club music enthusiast, Kai von der Lippe. Together with drummer Elias Tafjord, Why Kai has been a staple on club stages including Jaeger, and has recorded a few seminal EPs since establishing the project. At that convergence of the dance floor and Jazz, Why Kai lives closer to the loop-based phenomena that dominates club music, plying their craft in the physicalíty of their instruments.

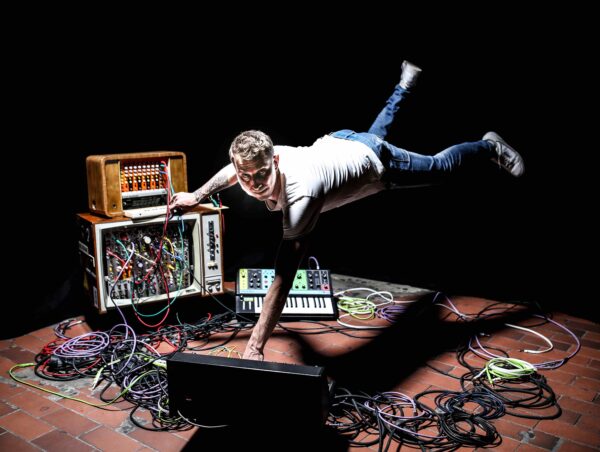

Fingers dancing over keys while percussive elements permeate with transcendental grooves, Why Kai’s music is made from the technical ability of accomplished musicians but thrives on the dance floor. As a live band it’s as appealing as a visual spectacle as it entices in the sonic realm and for the few EPs they’ve released it’s something that they’ve echoed remarkably well in the recorded format.

They take this a step further with their debut LP, “The Tourist” with Kai enlisting the skills of Elias in a more dominant way in the recording process. It sounds like Why Kai performing in your living room, and some familiar songs from their live repertoire evoke images of the duo on stage through the record.

A sweeping narrative in sound transports the listener through songs and vignettes that relay some hidden plot through its 12 songs. Between keys and drums the tracks are instantly familiar if you’ve heard Why Kai on stage before. Leaving enough room for the pulse to take root, songs develop in organic, and often very technical ways that encourage deeper listening.

On a weekday in Oslo, we caught up with Kai and Elias in a cafe in Grünnerløkka to find out what lies beyond the obvious in their debut record and the history of the project ahead of the official launch of “The Tourist” at Jaeger.

Kai, you mentioned this is a solo project. However, the few times I’ve seen you play live as Why Kai, it’s always Elias on the drums. Is it still a solo project?

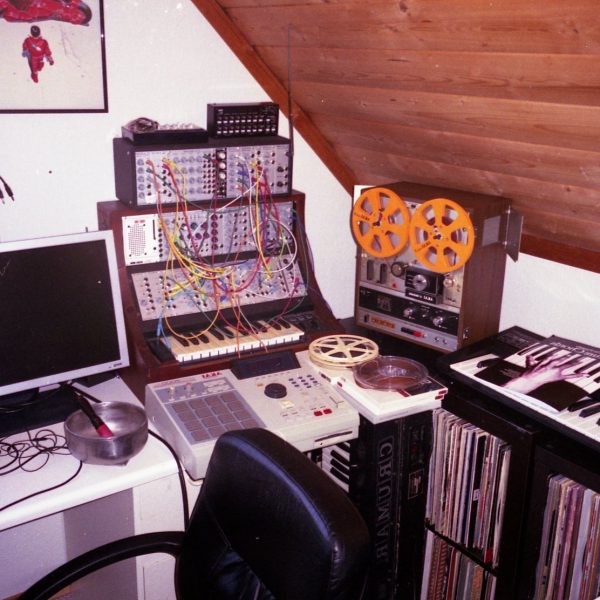

Kai: It has become more of a duo project, and then we sometimes play with a bigger band live, depending on the setting. On the recordings, it’s me making the music and Elias creating the drum parts, especially now on this album. It’s a blend of electronic drums and acoustic drums.

Elias: We always start with a base of electronic drums, but now we’ve started experimenting with acoustic drums. When we play live, I always use effects on the acoustic drums and combine those with the electronic drums.

Who programmes the electronic drums?

E: That’s Kai.

K: But the drums are important. Without the acoustic drums it would have been static.

E: It also makes it quite different from other electronic artists, because of the acoustic elements; like the drums and the piano.

There is something quite visually appealing to seeing somebody actually play the drums in the club setting.

K: It’s so visual and such a whole body experience.

You’re both quite accomplished musicians and you’ve obviously studied music at a high level. Is that how you met each other?

E: We actually found out that we’re from the same neighbourhood recently, but we only met at Foss, the music high-school. I think the teacher saw us as the Jazz guys. As we got older, we started dancing a lot together, going to Jaeger a lot on Tuesdays and Saturdays. We found we had this common love for electronic dance music.

Did you have a Jazz background before going to high school?

K: Both of us have parents who are Jazz musicians. I started with classical piano lessons and then moved from that to playing with a jazz teacher at Kulturskolen at Grønnland.

E: I grew up with my dad touring a lot when I was a kid. So, when my mom couldn’t handle me, I went on tour with my dad. He was a tuba player that played in this traditional world Jazz band.

K: You had the drummer of that band as your teacher.

E: Yes, and my teacher had the drummer before him as a teacher. I’m third in the line.

That’s a dynasty! What kind of Jazz were you exposed to at that early age?

E: I was more of a New Orleans traditional Jazz kind of a guy, because that’s the stuff my dad played. He was also involved with some African- and Asian musicians. It was a blend between world- and New Orleans Jazz.

K: The early stages, I was also a product of what my dad listened to and played. Which was the Bill Evans and Keith Jarret style of Jazz piano.

So, not too experimental?

K: No. When I started at high school I got into Bugge Wesseltoft and Nils Molvær and clubby jazz from the nineties here in Norway. When at university, that‘s when I really started experimenting with freeform Jazz, but that’s true for both of us I think.

E: My sister is also an electronic noise musician. Getting that from early on as well, put me on that path.

What brought you guys together and how did the solo project arrive?

K: We had another trio, playing club music. It was a collective thing and more showy.

E: It was almost like a rock show, with us going; “fuck you, we’re playing club music!” We had silver tights as costumes with hair and makeup. The other person was a raver/clubber, and we thought we had to make this music that we listen to all day.

It sounds a bit like LCD Soundsystem or !!!. Is that what you were listening to?

E: We hadn’t dived into those groups yet.

K: It was more like Techno and Deep House. When making this music it was a mix of the fact that we can play it, and it gets more show-based.

In terms of going from the three-piece to Why Kai, what was the major change in the music, besides the fact that you were missing one person.

K: I went abroad to Copenhagen to study, and they were very focussed on what is your sound, what’s your music. That’s when I started making this music, and that turned into the first EP. Coming back to Norway, I started thinking about how I would play it live. Unlike the other project which had the live element as the main focus, Why Kai was more about making a record, and then afterwards thinking about how we’re gonna play it live.

Why is this live aspect so important to you?

K: The whole project is about organic played music meets static electronic music. It’s very natural to play live with live musicians, and we come from playing live. We’re not so much studio rats.

E: We’re Jazz cats. (laughs)

Were there any particular objectives in creating a sound for Why Kai?

K: I listened to a lot of Norwegian composers that were not in the electronic music field. I saw similarities in some of their compositions and electronic club music, in the way they were built up. They’ll have a groove going, with interesting elements evolving on top. Most of the club music I listen to is very minimal, based on the loop. I wanted to bring the development of the compositions in Jazz to club music.

Not to disparage electronic music, but do you ever feel that you have to dumb it down a bit as accomplished Jazz musicians, or can you incorporate those more complex ideas from Jazz into this music?

E: Yes, of course. The whole harmonic and tonal world Why Kai moves in, is very influenced by Jazz. It might be a bit subjective, but I feel when you start a Jazz solo, it’s very much like Techno music; you have to build up a room. It’s the same principle in electronic music, that the audience can just sit there and enjoy the flow of energy.

K: Of course there are elements like playing situations to consider. If you’re playing late night between DJs, for example, you can’t have too many slow, low energy moments. We will compensate for that. And on the other hand if we’re playing for a Jazz festival to a sitting audience, then we’ll have to adapt the music again.

If the context of a Why Kai concert can go from a Jazz festival to a nightclub, is there a specific audience in mind when you’re creating the music?

E: No, but it’s for the dancing audience.

K: At the same time, I don’t want to tie myself down to one particular audience in the making of the music. I try to just follow what’s on my mind.

There is something to the recorded material that relays the way you sound as a live band. Is that a consideration when you approach the recording process and specifically something you had in mind for ”The Tourist”?

K: Yes, I usually make it without playing as a band. On this new album however we have some parts that were recorded as jams, that we chopped up afterwards. And then we’d improvise over that again. But most of the songs are based on a production setting.

E: What we did there was improvise around an idea. There were perhaps some boundaries. We’d probably used 20 seconds of 30 minutes of improvisation.

K: Most of the melodies, which were composed, were also born from improvisation.

Why an album and why now?

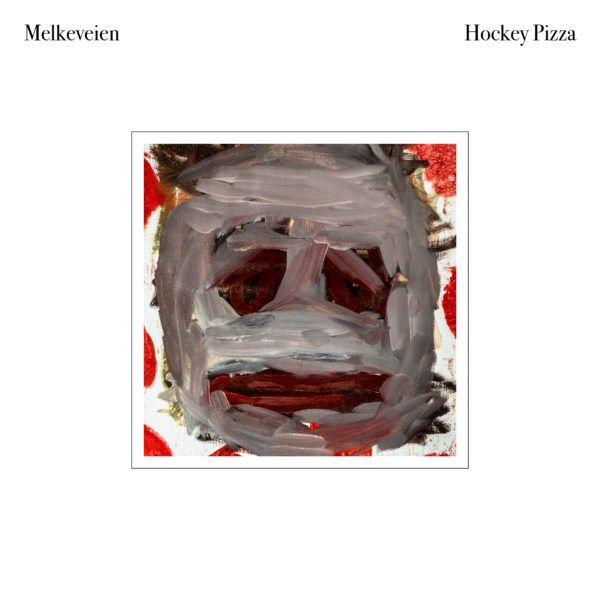

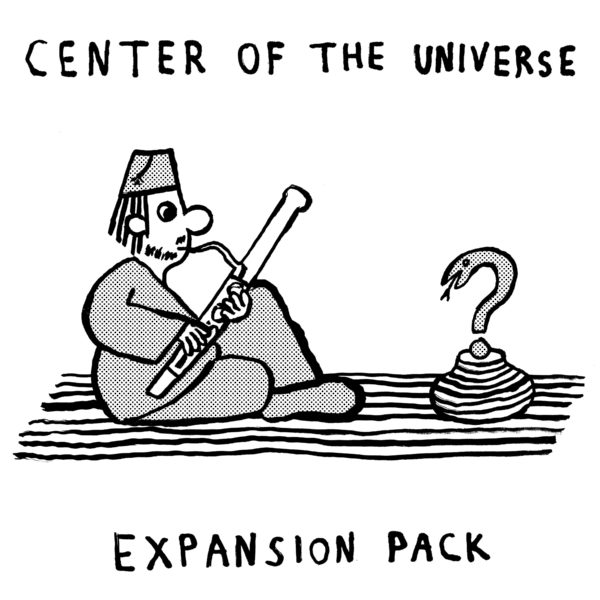

K: Because it was finished, I guess. (laughs) It was a long process. The music was composed over a year ago. We started a label for electronic music, so setting that up and learning that process happened at the same time.

Is it any different from the first EP, because it sounds like it was made around the same time as the EP?

K: Some of the tunes are a bit like the first EP, but then I wanted to move away from it too, so some of the tunes are quite different in my opinion.

Do you feel that you’ve found something with this album that perhaps wasn’t there at the start of the project?

K: I’m not entirely sure. What the project will be in the future, isn’t dependent on this album. What I wanted to create – and it’s the same for the first EP – is that I didn’t want to use too many electronic sounds, and if I use them, I want them blended with acoustic sounds. I would chop up improvised samples from bass or prepared guitar and make a groove from that to get that organic feel.

Do you find there’s always a kind of challenge in incorporating electronic sounds in acoustic environments and vice versa?

E: At least in the live format; to blend these things to get the way we wanted the sound to sound. They are sonically different and if something is wrong it takes so long to fix it, and it almost removes the original idea completely. It’s way different than just hitting a drum or a piano; where you’ll know what to expect.

I feel it started from a perspective where the acoustic sounds were the boss, and the electronic bits were added, but now it’s slowly turning. Electronic sounds are so much more piercing. The machine is the boss. At the same time I realised it’s us that have to make the pre-sequenced things groove, it’s not those things that make us groove.

What I really liked about the album was this narrative that follows through it including these little musical vignettes that bridge certain songs. What was the idea behind that?

K: I had this idea of the whole album going into one piece, so the groove never stops. The songs are at different tempos, so some of those “vignettes” are accelerating or decelerating.

E: We went into the studio with an idea, which is kind of bold, because you can always slow down a track in the production, but we actually played those with the click track going down in tempo and then there’s no turning back from that. Kai worked it out beforehand.

K: And, in some vignettes, speeding the tunes up after the recording. The tonality changes when you speed the song up. So, we had to calculate what that tonality would be in reference to the changing BPM.

E: There was a lot of maths going on.

Do you think alot about sound-design in the recording process?

K: Yes for sure. To some extent, to not get it to sound like a specific instrument. A lot of the melodic sounds are a mix of some synthesiser and a prepared piano.

Are there some other musicians present on the album, because at some stage I hear some double bass?

K: Yes I asked some friends that play bass to play these notes and do some weird improv sounds, and then I would chop it up afterwards.

E: The last single, “Creator of the Salt”, that’s that idea.

How do you translate that type of thing back into the live context again?

K: This is what we’ve had some problems with. In some sense many of those chopped sounds are the sound of the project. It’s pretty hard to replicate the same sort of idea live.

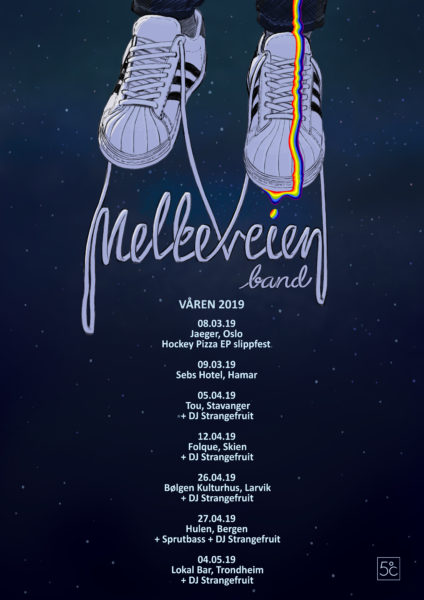

But it will still just be you two playing live at jaeger for the album release?

K: Yes, but for Jaeger, because of the club setting.

How has it informed your work beyond the DJ booth and in the studio?

How has it informed your work beyond the DJ booth and in the studio?

What do you remember of the nights at Space @ Bar Rumba?

What do you remember of the nights at Space @ Bar Rumba? How did you and Honey start working together?

How did you and Honey start working together?

You mentioned, Garage was big when you were teenagers. Is that around the same time you started to make music?

You mentioned, Garage was big when you were teenagers. Is that around the same time you started to make music?

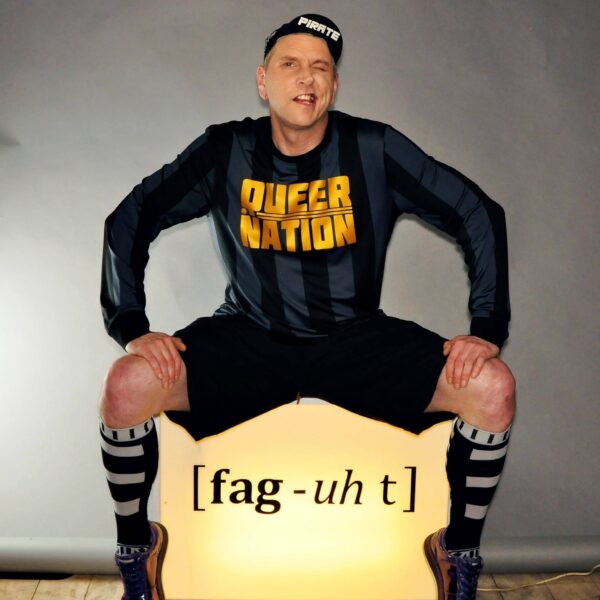

James doesn’t feel queer is a “sexual statement,” but rather an ideology. “I know cis straight woman who identify as queer,” he says as an example. For James, queer is about a “rejection of patriarchy” and a the celebration of “alternative lifestyles” on dance floors. “As long as they bring love and joy to the dance, then everybody is welcome,” insists James. Even though the party they “do in New York is a different crowd to the one in London and the one in Berlin is different to both of those,” that queer element remains at its core and James “love

James doesn’t feel queer is a “sexual statement,” but rather an ideology. “I know cis straight woman who identify as queer,” he says as an example. For James, queer is about a “rejection of patriarchy” and a the celebration of “alternative lifestyles” on dance floors. “As long as they bring love and joy to the dance, then everybody is welcome,” insists James. Even though the party they “do in New York is a different crowd to the one in London and the one in Berlin is different to both of those,” that queer element remains at its core and James “love

Tell me about WINDOWS. Is it an album and/or a live show?

Tell me about WINDOWS. Is it an album and/or a live show?

Ida and Naomi both grew up in what they consider a “small town” called Sandefjord. Both had taken an early interest in music albeit from different points of view. While Ida was “drawn into singing very early,” Naomi was an avid listener, consuming all she can from Beyonce to Dimmu Borgir. At around the age of 11 Naomi’s dad built her a dance studio in the basement with “some cheap speakers and different kinds of disco lights” encouraging the impressionable youth towards electronic dance music. She would be “dancing like a crazy person to Benny Benassi” in her basement enclave she remembers fondly today.

Ida and Naomi both grew up in what they consider a “small town” called Sandefjord. Both had taken an early interest in music albeit from different points of view. While Ida was “drawn into singing very early,” Naomi was an avid listener, consuming all she can from Beyonce to Dimmu Borgir. At around the age of 11 Naomi’s dad built her a dance studio in the basement with “some cheap speakers and different kinds of disco lights” encouraging the impressionable youth towards electronic dance music. She would be “dancing like a crazy person to Benny Benassi” in her basement enclave she remembers fondly today.

You’re talking about the early nineties?

You’re talking about the early nineties?

Wilkes

Wilkes 13 years is still a long time for a club night, especially at that time, when everybody was going from one thing to the next quite quickly. How did you maintain that excitement around it for so long?

13 years is still a long time for a club night, especially at that time, when everybody was going from one thing to the next quite quickly. How did you maintain that excitement around it for so long?

You got pigeonholed as a DJ, somewhat unfairly, in that Deep House trend after “Your Everything.” What effect did it have on what you would do next and how did you eventually sidestep it as a DJ?

You got pigeonholed as a DJ, somewhat unfairly, in that Deep House trend after “Your Everything.” What effect did it have on what you would do next and how did you eventually sidestep it as a DJ?

Lars grew up in the

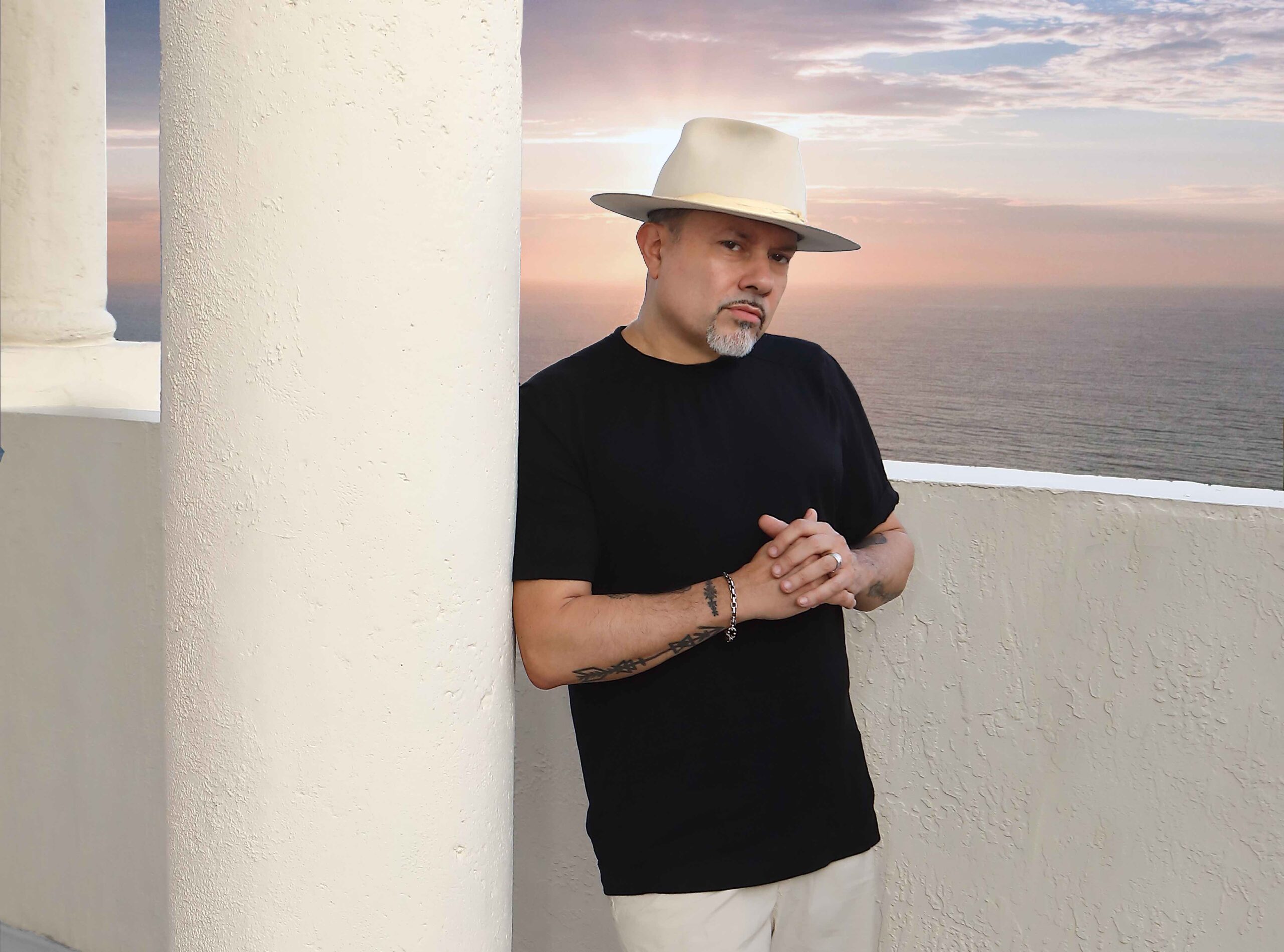

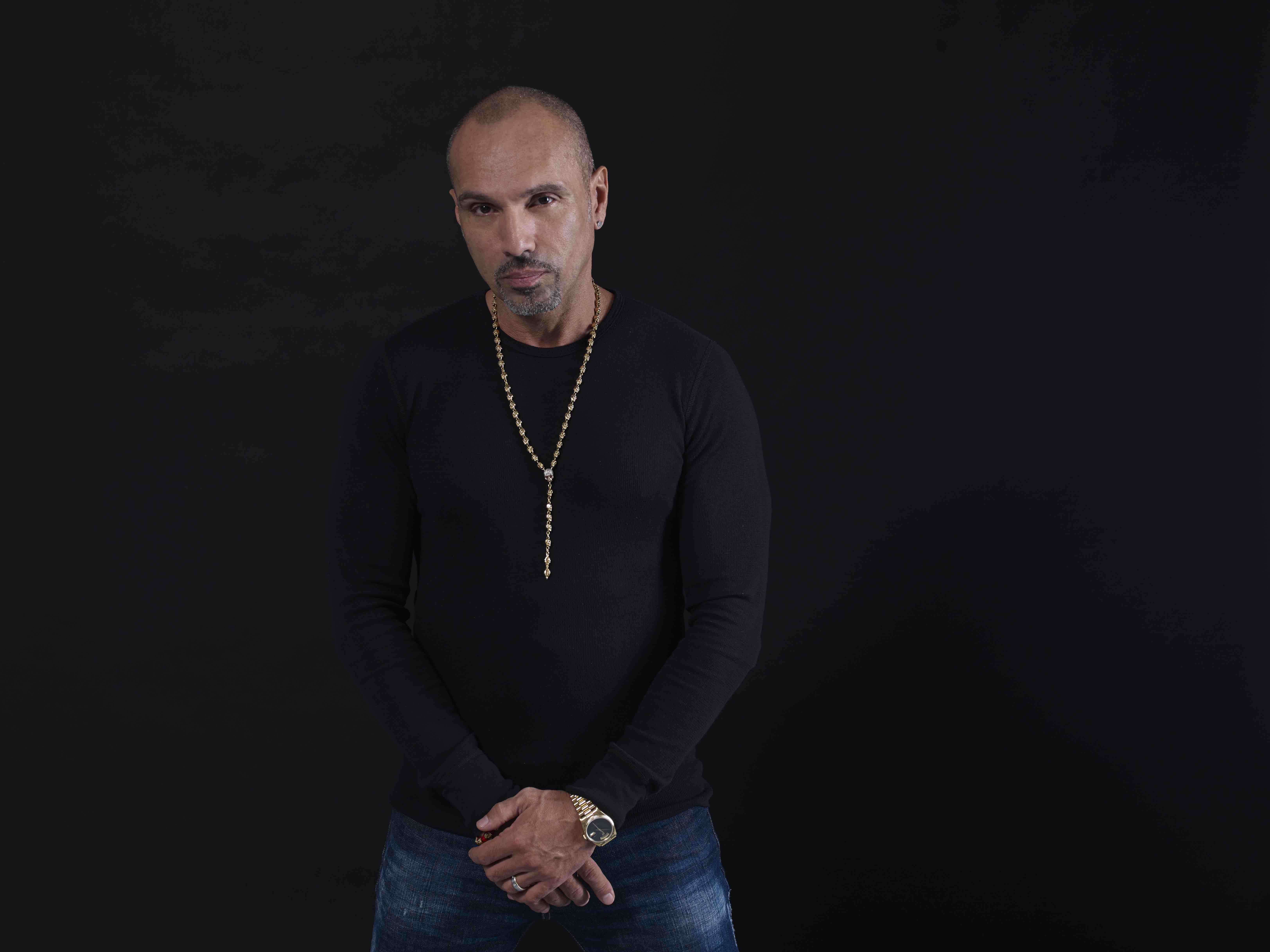

Lars grew up in the At 13 he had heard his first DJ playing Disco records consecutively, and by 15 he went to his first club and bought “Ten Percent“ on Salsoul. The speaker hanging out the window soon developed into a party in his apartment, and requests to play at other people’s house parties followed as he became a local mobile Disco music of some repute. “I just loved the music, it was just everything for me,” he remembers. At 18 he had made something of a career out of it, playing mostly commercial music, before somebody dropped “a stack of what they called Loft records” at his feet. “I was like ‘Whoa, what is this sound?’” It was a selection of expensive, limited press- and imported records, the kind of which they had been playing not only at the Loft, but also Paradise Garage. Although Morales had not yet been to either club, since they were strictly private clubs, he started making inroads as a dancer frequenting venues like Paradise Garage and the Loft through acquaintances with memberships, and eventually befriending people like Mancusso and DJ Kenny Carpenter. It was through Carpenter that he was inducted into a record pool, the first organisations that supplied DJs with new, unreleased music for the club, and it was through this pool that he would have his first major break as DJ.

At 13 he had heard his first DJ playing Disco records consecutively, and by 15 he went to his first club and bought “Ten Percent“ on Salsoul. The speaker hanging out the window soon developed into a party in his apartment, and requests to play at other people’s house parties followed as he became a local mobile Disco music of some repute. “I just loved the music, it was just everything for me,” he remembers. At 18 he had made something of a career out of it, playing mostly commercial music, before somebody dropped “a stack of what they called Loft records” at his feet. “I was like ‘Whoa, what is this sound?’” It was a selection of expensive, limited press- and imported records, the kind of which they had been playing not only at the Loft, but also Paradise Garage. Although Morales had not yet been to either club, since they were strictly private clubs, he started making inroads as a dancer frequenting venues like Paradise Garage and the Loft through acquaintances with memberships, and eventually befriending people like Mancusso and DJ Kenny Carpenter. It was through Carpenter that he was inducted into a record pool, the first organisations that supplied DJs with new, unreleased music for the club, and it was through this pool that he would have his first major break as DJ.

The first release on the label came via KiNK, with the aptly titled “Home,” and in that record we find similarities to KiNK’s music from “Under Destruction” as tracks play on similar rhythmic and melodic themes, distilled down from traditional music, with titles like The Clock and The Grid redefining the concepts contained in their titles for western ears. Accompanying the release and future releases from a small, but dedicated community of artists, are a series of photos – most of which taken on phone – from Bulgarian DJ legend DJ Valentine. Alongside the music it consolidates a label that for the first time will distill some of that Bulgarian traditions into a contemporary platform.

The first release on the label came via KiNK, with the aptly titled “Home,” and in that record we find similarities to KiNK’s music from “Under Destruction” as tracks play on similar rhythmic and melodic themes, distilled down from traditional music, with titles like The Clock and The Grid redefining the concepts contained in their titles for western ears. Accompanying the release and future releases from a small, but dedicated community of artists, are a series of photos – most of which taken on phone – from Bulgarian DJ legend DJ Valentine. Alongside the music it consolidates a label that for the first time will distill some of that Bulgarian traditions into a contemporary platform.

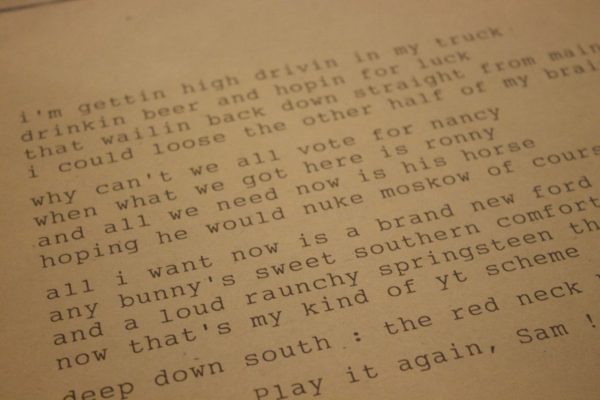

They had known they “had something by the first record” , the rather wordy “some, but not all Cheese comes from the moon.” That record, released on Planet Noise in 2004 had put Ost & Kjex on the map in Norway, but it was when they “sent the first tracks to Crosstown Rebels and they called back” they had something special according to Petter. “When Crosstown Rebels called up, we knew the outside world was listening” reiterates Tore and by the time of Cajun Lunch their sound was truly established.

They had known they “had something by the first record” , the rather wordy “some, but not all Cheese comes from the moon.” That record, released on Planet Noise in 2004 had put Ost & Kjex on the map in Norway, but it was when they “sent the first tracks to Crosstown Rebels and they called back” they had something special according to Petter. “When Crosstown Rebels called up, we knew the outside world was listening” reiterates Tore and by the time of Cajun Lunch their sound was truly established.

Do you remember a specific moment or track that inspired you to first mix two songs together?

Do you remember a specific moment or track that inspired you to first mix two songs together?

Tell me about going to the Loft.

Tell me about going to the Loft. Did he just play on Blå’s soundsystem?

Did he just play on Blå’s soundsystem? Did you ever talk to him about the peak era of the Loft?

Did you ever talk to him about the peak era of the Loft?

She gives my a side glance before answering; “Obviously there is a correlation… do I need to follow that…. A bit if I want to, but not really.” It’s understandable why she won’t acquiesce to the archetypes that dominate DJ culture today. As she insists, she

She gives my a side glance before answering; “Obviously there is a correlation… do I need to follow that…. A bit if I want to, but not really.” It’s understandable why she won’t acquiesce to the archetypes that dominate DJ culture today. As she insists, she

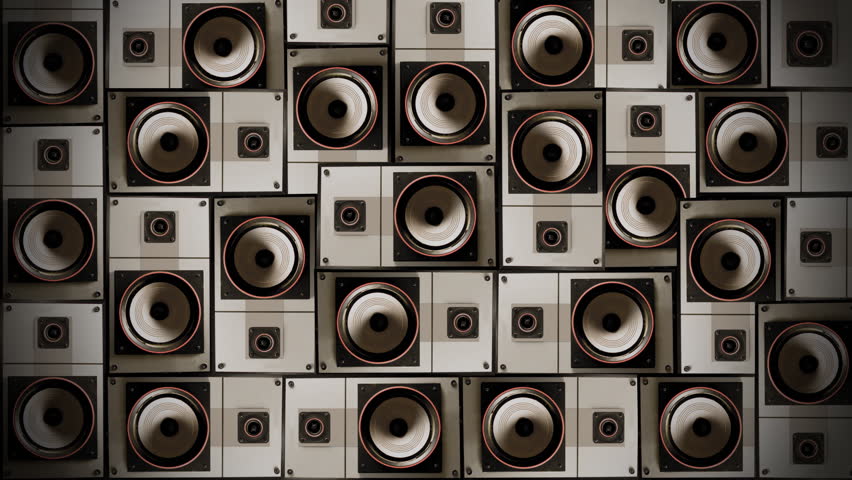

That was my introduction to Jaeger’s “Diskon sound” as I came to know it and throughout my tenure here, the sound system kept growing, shrinking and moving in a constant evolution that owner and resident Ola Smith-Simonsen (Olanskii) still refers to as a ”work in progress.” It’s been in a constant state of flux that has taken a life of its own as the venue, the DJs and the audience kept changing around it and as it kept retreating further into the structural makeup of the room and the dance floor it’s allure is indistinguishable between these elements. And as Ola starts talking about the next phase of the system and the recently-installed bass traps settle into the walls, it’s an evolution in sound that refuses to come to any natural conclusion.

That was my introduction to Jaeger’s “Diskon sound” as I came to know it and throughout my tenure here, the sound system kept growing, shrinking and moving in a constant evolution that owner and resident Ola Smith-Simonsen (Olanskii) still refers to as a ”work in progress.” It’s been in a constant state of flux that has taken a life of its own as the venue, the DJs and the audience kept changing around it and as it kept retreating further into the structural makeup of the room and the dance floor it’s allure is indistinguishable between these elements. And as Ola starts talking about the next phase of the system and the recently-installed bass traps settle into the walls, it’s an evolution in sound that refuses to come to any natural conclusion.

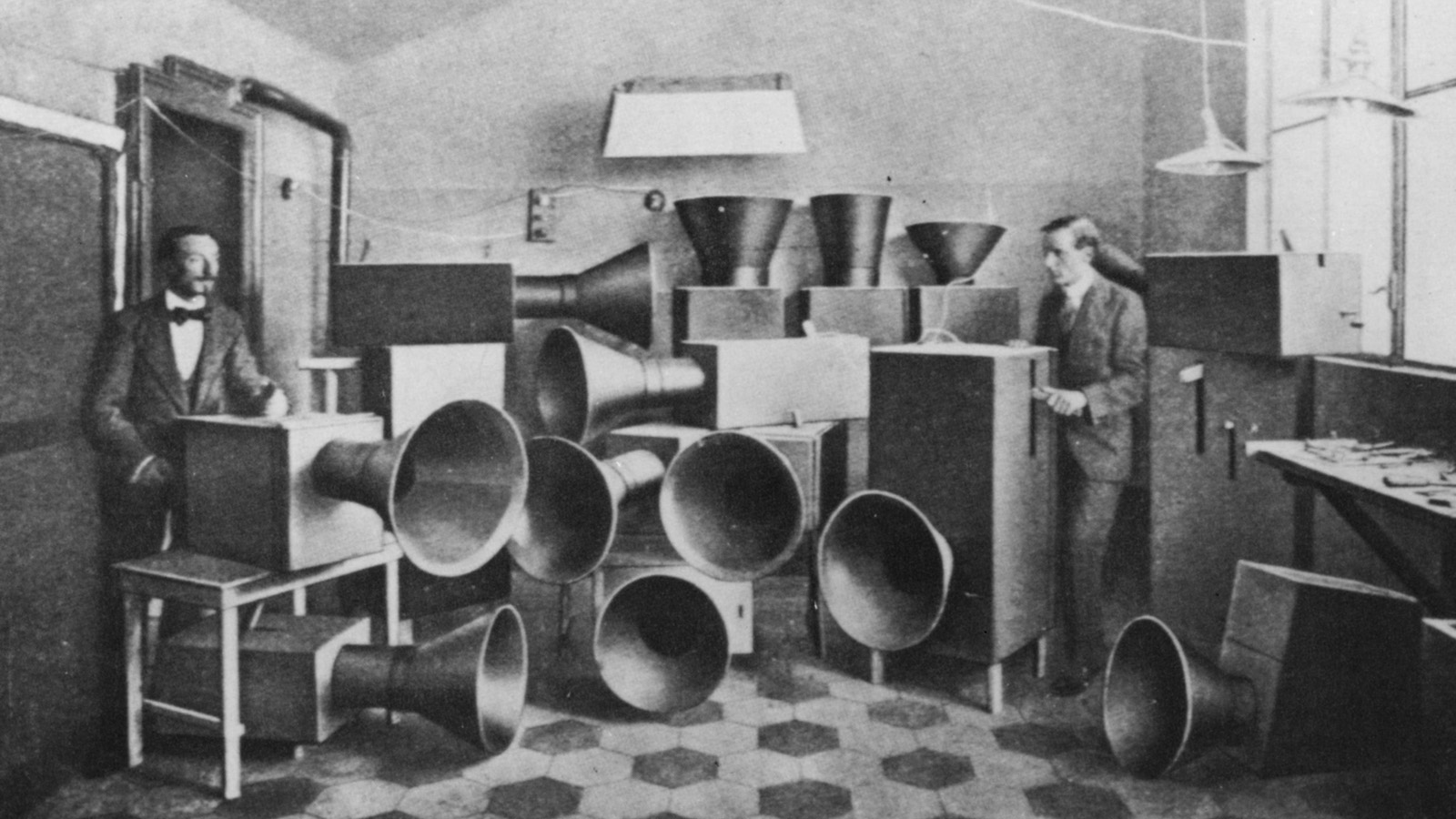

“It’s like money,” collates Rosner in a RBMA lecture; ”you can never have too much because you know you can give some of it away. Loudspeakers can never be too big, because you can always turn the volume down.” In one of Rosner and Mancuso’s crowning achievements at the Loft their combined efforts resulted in creating a tweeter-array system that helped spread those higher sonic frequencies more evenly and further across the room, so that even the person sitting in the back could hear every element in the music rather than just the bass frequencies, which naturally has the longest reach. Even though Rosner didn’t initially agree with Mancuso’s tweeter array idea, he soon came around when he discerned ”the more you have up there the better.” It’s a sonic philosophy that’s still noticeably adopted today when you see towers of horns jutting out high above the DJ somewhere like stalagmites on a cave wall, but while it’s certainly helpful having all that sound on tap, it’s pretty pointless if it’s not pointed in the right direction.

“It’s like money,” collates Rosner in a RBMA lecture; ”you can never have too much because you know you can give some of it away. Loudspeakers can never be too big, because you can always turn the volume down.” In one of Rosner and Mancuso’s crowning achievements at the Loft their combined efforts resulted in creating a tweeter-array system that helped spread those higher sonic frequencies more evenly and further across the room, so that even the person sitting in the back could hear every element in the music rather than just the bass frequencies, which naturally has the longest reach. Even though Rosner didn’t initially agree with Mancuso’s tweeter array idea, he soon came around when he discerned ”the more you have up there the better.” It’s a sonic philosophy that’s still noticeably adopted today when you see towers of horns jutting out high above the DJ somewhere like stalagmites on a cave wall, but while it’s certainly helpful having all that sound on tap, it’s pretty pointless if it’s not pointed in the right direction. It was Alex Rosner that introduced Long to this world, as a kind of fixer for his sound systems and it would be Rosner that would also inadvertently put him into business. In “Last night a DJ saved my life,” Francis Grasso described an incident where Rosner sent Long out on a job, and Long usurped his boss by outbidding him on the same job as an independent contractor. Rosner remembers it differently in the RBMA documentary. According to Rosner, John Addison (Studio 54) had phoned Rosner up in the middle of the night to ask about doing some work for him. Rosner swiftly hung up on Addison, noting the lateness of the call in what I assume was short conversation littered with expletives. Addison in all his ‘70s cocaine-fuelled cock-sured fury was not a person you would hang the receiver up on likely and put his next call in to Rosner’s budding apprentice effectively putting Richard Long and associates into business.

It was Alex Rosner that introduced Long to this world, as a kind of fixer for his sound systems and it would be Rosner that would also inadvertently put him into business. In “Last night a DJ saved my life,” Francis Grasso described an incident where Rosner sent Long out on a job, and Long usurped his boss by outbidding him on the same job as an independent contractor. Rosner remembers it differently in the RBMA documentary. According to Rosner, John Addison (Studio 54) had phoned Rosner up in the middle of the night to ask about doing some work for him. Rosner swiftly hung up on Addison, noting the lateness of the call in what I assume was short conversation littered with expletives. Addison in all his ‘70s cocaine-fuelled cock-sured fury was not a person you would hang the receiver up on likely and put his next call in to Rosner’s budding apprentice effectively putting Richard Long and associates into business.

“Drugs, nothing more,” says Tornike, but “when they raided the club, no-one was arrested for dealing drugs and they couldn’t find any drug dealers inside the club, only finding 2 or 3 grams” on individuals. The club owners were arrested too, without a warrant on some overblown claims of obstruction, which never resulted in any charges brought forward, but what happened directly after the raid, was a force of solidarity in a clubbing community that we haven’t seen since the time of the criminal justice and public order act. People like Tornike, who had started gathering outside Bassiani as the police were carting off their friends and colleagues, were protesting the arrests. “We were trying to figure out what was happening,” explains Tornike who “didn’t even know which Police station they took them to” at the time.

“Drugs, nothing more,” says Tornike, but “when they raided the club, no-one was arrested for dealing drugs and they couldn’t find any drug dealers inside the club, only finding 2 or 3 grams” on individuals. The club owners were arrested too, without a warrant on some overblown claims of obstruction, which never resulted in any charges brought forward, but what happened directly after the raid, was a force of solidarity in a clubbing community that we haven’t seen since the time of the criminal justice and public order act. People like Tornike, who had started gathering outside Bassiani as the police were carting off their friends and colleagues, were protesting the arrests. “We were trying to figure out what was happening,” explains Tornike who “didn’t even know which Police station they took them to” at the time.

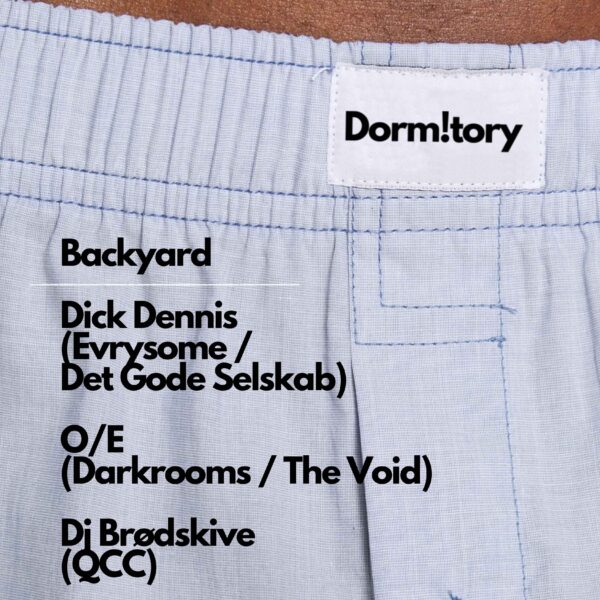

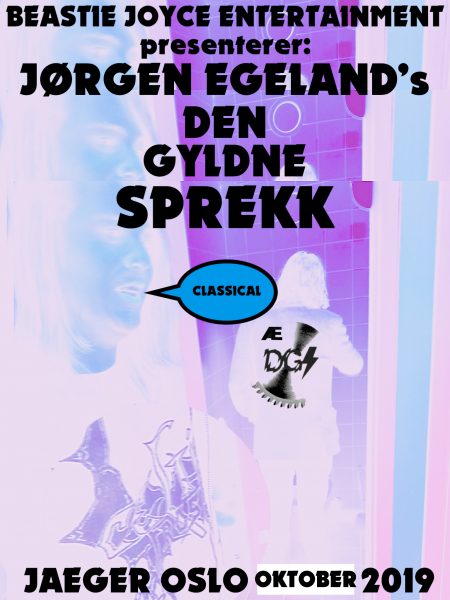

In the month of October, DJ Lekkerman hands over the reigns of his weekly residency to a couple of stalwarts on Den Gyldne Sprekk roster, and two DJs and music enthusiasts that know the concept inside out. Beastie Joyce and Jørgen Egeland host another month of Den Gyldne Sprekk at Jaeger with a series of concepts that go from another KIZZ pøb to the blood-curdling sounds of Memphis Rap for Halloween as the pair resurrect their Funk Boys alias to invite a host of kindred spirits to the lineup for October.

In the month of October, DJ Lekkerman hands over the reigns of his weekly residency to a couple of stalwarts on Den Gyldne Sprekk roster, and two DJs and music enthusiasts that know the concept inside out. Beastie Joyce and Jørgen Egeland host another month of Den Gyldne Sprekk at Jaeger with a series of concepts that go from another KIZZ pøb to the blood-curdling sounds of Memphis Rap for Halloween as the pair resurrect their Funk Boys alias to invite a host of kindred spirits to the lineup for October.  KIZZ PØB returns! What is it about the band in your opinion that continues to draw old and new fans to their music?

KIZZ PØB returns! What is it about the band in your opinion that continues to draw old and new fans to their music?

How did you feel your set at Jaeger went?

How did you feel your set at Jaeger went? Do you consider yourself a veteran of the scene in that respect?

Do you consider yourself a veteran of the scene in that respect?

The music you guys make on Rebound to me sounds like its all built on a foundation of House, but there’s also that frosty Norwegian sonic element in there. What conscious steps do you take in creating that sound?

The music you guys make on Rebound to me sounds like its all built on a foundation of House, but there’s also that frosty Norwegian sonic element in there. What conscious steps do you take in creating that sound?

I spoke to Carl Craig recently and he told me that DJing was the day job to afford the passion of making music. But I have a sneaking suspicion that’s the other way around for you, that DJing is the true passion?

I spoke to Carl Craig recently and he told me that DJing was the day job to afford the passion of making music. But I have a sneaking suspicion that’s the other way around for you, that DJing is the true passion?

I think it would’ve been that way. I know DJs who just don’t have the attention span to make music. Some guys from Detroit I would really like to see out here, more. They are excellent DJs, but just don’t get the opportunity because they don’t have the patience to sit around and programme music.

I think it would’ve been that way. I know DJs who just don’t have the attention span to make music. Some guys from Detroit I would really like to see out here, more. They are excellent DJs, but just don’t get the opportunity because they don’t have the patience to sit around and programme music.

Jann Dahle started making music in 1992 in Tromsø when he moved there to study law. It was a fortuitous time to be making music in Tromsø as the critical point for a burgeoning Disco and House scene that would eventually spread around the globe. “I met Rune (Linbæk), Bjørn (Torske) and Kolbjørn (Lyslo aka Doc L Junior) and I started professionally DJing back then,” remembers Dahle. “There was a lot of buzz about Norwegian Disco at that moment, because of Bjørn,” but Tromsø being a small city, Dahle “got to know everybody” involved in music and landed a job at Brygge Radio alongside Bjørn, Rune, and Geir Jenssen (aka Biosphere).

Jann Dahle started making music in 1992 in Tromsø when he moved there to study law. It was a fortuitous time to be making music in Tromsø as the critical point for a burgeoning Disco and House scene that would eventually spread around the globe. “I met Rune (Linbæk), Bjørn (Torske) and Kolbjørn (Lyslo aka Doc L Junior) and I started professionally DJing back then,” remembers Dahle. “There was a lot of buzz about Norwegian Disco at that moment, because of Bjørn,” but Tromsø being a small city, Dahle “got to know everybody” involved in music and landed a job at Brygge Radio alongside Bjørn, Rune, and Geir Jenssen (aka Biosphere).

When and how did Techno exactly come into your life and what drew you to the genre?

When and how did Techno exactly come into your life and what drew you to the genre? What do you look for in a Techno track to make it into your sets?

What do you look for in a Techno track to make it into your sets?

Channeling that experience of touring and playing live into this record, Dave Harrington Group favour an uninhibited approach on “Pure Imagination, No Country” as they capture that raw intensity and power of a live band in the studio. Nick Murphy emphasises this energy through post production, which on their previous LP, favoured a slicker, more refined approach. Dave Harrington’s guitar takes more of a central role on the LP, where it appears mostly unprocessed in its natural state taking the stage front and centre in the production across the album.

Channeling that experience of touring and playing live into this record, Dave Harrington Group favour an uninhibited approach on “Pure Imagination, No Country” as they capture that raw intensity and power of a live band in the studio. Nick Murphy emphasises this energy through post production, which on their previous LP, favoured a slicker, more refined approach. Dave Harrington’s guitar takes more of a central role on the LP, where it appears mostly unprocessed in its natural state taking the stage front and centre in the production across the album.

Working with TB Arthur and people like BMG, do you think It’s changed the way you make music?

Working with TB Arthur and people like BMG, do you think It’s changed the way you make music? Like every DJ out there today you have an agent that takes care of your bookings, but do you have the final say where you’ll play?

Like every DJ out there today you have an agent that takes care of your bookings, but do you have the final say where you’ll play?

Why these particular remix artists?

Why these particular remix artists?

I’ve read that your philosophy is about exporting the Black Motion, and in extension the South African sound to the wider world.

I’ve read that your philosophy is about exporting the Black Motion, and in extension the South African sound to the wider world.