While our construction / bar crew are hard at work gutting the inside of Jæger as part of our renovations, those of us less adept at manual labour – exclusively me (It took me an hour to remove one hand dryer attached to a wall with two screws) – have taken the time to catch up on some reading. Resident Advisor’s longer reads in particular and while they’re not always convenient to read they are almost always insightful, but something about they’re latest article needs to be heard by as many people involved or participating in clubbing culture as possible. So I’ve taken to summarising the piece for those of you who don’t have the time to indulge in the extended piece, because it’s time we really start talking about drugs and it’s role in clubbing culture like adults.

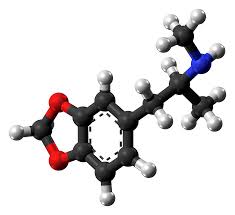

Drugs have been synonymous with clubbing culture since time immemorial. Whether it was psych rock and LSD in the 1960’s; speed and the punk scene, Heroin and Jazz in the 1950’s; Ecstasy and Rave culture; or even the rise of cocaine in Oslo’s clubbing landscape recently, drugs have always been a part of clubbing culture and it would be incredibly obtuse to ignore that fact. And with club culture completely entangled in electronic music today the two are almost one in the same. This is not to suggest that Jæger condones the use of drugs (hell, we don’t even allow energy drinks), but like Sacha Lord-Marchionne from The Warehouse Project says in the article; “We would be morons to think that, no matter what measures we put in place, people aren’t going to get drugs into the venue.” Luis-Manuel Garcia approaches the issue of Drug Policies and Electronic music culture in this article by looking at what is the most effective policy on drugs in the UK at this moment, which is WHP and the way they operate within the law to give the punters that might indulge in drugs the safest way to do that, distributing information about harmful substances they might come in contact with by allowing experts to test any confiscated drugs. This is called a “harm reduction” strategy in the article and it seems that the most effective way of combating drug abuse is still that model of a weary hippy standing on rickety stage, telling the audience at the first Woodstock that the brown acid is a bad trip. Because drug policies are still too constricting to let researchers and scientists do their job and find affective measures to have some sort of quality control over the drugs we injest. Drug policies it appears occupy a scale from eradication-focussed zero tolerance policies to Harm Reduction. “Harm-reduction policies tend to be less pathologising, seeing drug users as normal, everyday people, most of whom partake in drugs in culturally-specific settings that only rarely lead to harm.” Think of the “needle rooms” in Norway in the context of a recreational drug like MDMA or Ketamin. This article focuses mostly on the USA and it’s draconian war on drugs, which resulted in the Rave Act of 2003, “which extended laws intended for ‘crack houses’ to make the organisers of raves and other dance music events legally responsible for drug use on their premises.” And it Garcia poses the question “are you willing to increase the risk to drug users in order to drive drugs underground?”

In the article Garcia speaks to people like Stephanie Jones and organisations like Dance Safe to make a case for reforming drug policies and especially introducing harm reductions policies in venues, organisations and festivals. It seems that the current drug policies not only stop organisers, venues and festivals from implementing measures to educate their audiences about drugs, but also encumber researchers like Dr. Doris Payer from studying the effects of recreational drugs and how to prevent harm to users. Because with all that we know today, there is reason to suggest that drugs can be safe in a controlled environments with small quantaties and no more harmful than alcohol or cigarettes. Garcia suggests there is a cultural stigma around drugs as dictated by these current policies and that “(t)here may have been times when we have failed to look after ourselves and each other because of deep-seated, culturally-ingrained morals about pleasure and propriety.” It’s in essence a kind of hypocrisy where even those who indulge in drugs, safely and without real harm, tend to associate the activity as akin to the gangsters shooting each other over the right of a distribution area. It encouraged me to believe once again to fight drugs on a universal level rather than a national level and the article makes several references to the Netherlands and Portugal’s stance, where it’s still illegal, but the police’s resources are focussed more on preventing the organised crime that naturally evolves around supplying something illegal – like bootlegging during prohibition.

Garcia doesn’t broaden his approach on a universal scope like this, but rather focuses his attention on something that’s far more realistic for this time and place, and returns to harm reduction policies and the best solution for making sure those that do take drugs don’t come to harm, because of unknown and harmful contaminate substances. It appears that it’s something we’ve been doing for as long as we’ve been taking drugs at clubs, developing something of buddy system when we do indulge. “Ravers are remarkably resourceful when it comes to managing drug safety under clandestine conditions,” says the article. It appears with prohibitive drug policies enforced by heavy handed security with adverse affects to the drug user, we form a tight knit community, where we look out for one another through a network system, a sort of ground roots Harm Reduction strategy if you will. The article goes on to say this can have disastrous consequences, but fails to mention how, and suggests that it’s only through tightly managed systems like on-sight testing that these systems have a controlled effect. For the moment places like WHP can only really test the drugs that are confiscated, and post a notice to warm of any harmful effects. But the most effective harm reduction strategy would actually be onsite testing for potential drug users and for the most part this is still illegal, since anybody handling the substances could be prosecuted for possession, and that’s the case for Norway too – even though punishment for possession is fairly light with 6 months the longest jail sentence for small quantities.

This is why Garcia says it’s important to educate and familiarise ourselves with drug policies, because they in turn have a fundamental affect on clubbing culture and the dance floor. It can save a person from intoxication and death if reformed and even if you don’t use drugs, it can still impact those around you if you are a part of club culture. You can read the full article here if you feel compelled to dig deeper and would urge you to do just that.