We talk to Kim Dürbeck about Urchin remixes and his Vietnamese roots while we premiere a previously unreleased track from the artist.

Kim Dürbeck has been nothing short of prolific in the last two years. His Bandcamp account and Soundcloud page has seen a flurry of activity, cementing a new era for the producer and artist. It was all a means to an end during the lockdown period; “ to keep doing something while not DJing” as he explains over a telephone call. In its wake, however, it has created a new artistic phase for Kim. He’s in his hometown Sandjefjord when I call, about an hour and a half outside of Oslo, and yet Kim is no stranger to nightlife in Oslo.

A regular guest at Jaeger, he’s carved out a career based on his skills as a DJ that’s travelled far beyond the small and isolated coastal town of Sandefjord. He is one of the leading lights in an underground clubbing community that stretches across Norway and before the pandemic, he could often be found travelling the world with a record bag. Lately he’s focussed those skills and vast musical experience into his production work. Like many of his peers, Kim has been “stuck in the studio” these past two years and he’s been busy.

Urchin

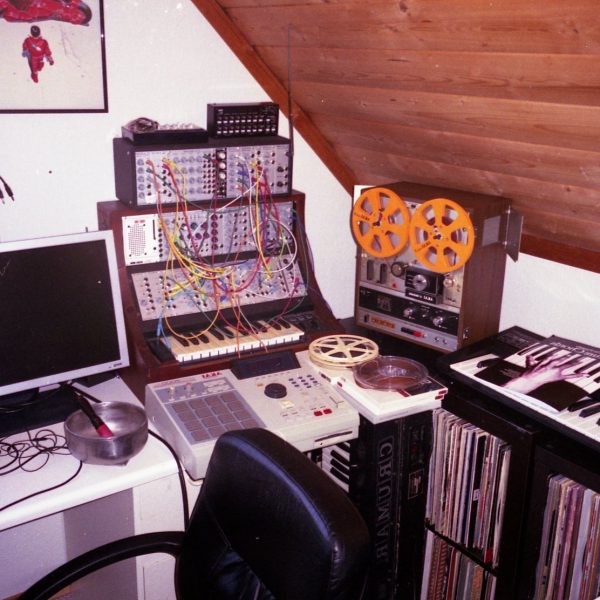

“Would you like an unreleased track for the article,” he asks during our call. “A premier,” I suggest. “I have so many at the moment,” he says in nonchalant confirmation. He’s not boasting. Ensconced in his studio these past two years, surrounded by an arsenal of hardware synthesisers, drum machines and grooveboxes, he’s released a host of EPs on his own and contributed to compilations for HMD and the Vietnamese outfit Nhạc Gãy.

He’s been most active on Soundcloud and Bandcamp and coming via the latter he’s now also the first of possibly two remix packages for “Urchin.” André Bravo, Curtis Vodka, Cato Canari, JaJa Saine and Dustin Ngo contribute their interpretations of Kim’s Jungle-Acid original.The track, initially released two years ago, is something of a watermark in the career of Kim Dürbeck.

Urchin is a track that falls somewhere between the gaps of some left-field club genres. “It’s between Acid and Jungle,” says Kim by way of reiterating. Featuring a “simple break” that is also “not that aggressive” it’s not an easy track to pigeonhole. The Jungle element is there in the drums, and yet it is restrained. The lysergic 303 pledges its allegiances to Acid, but it almost disappears in the dense textures of the harmonies. The synthesised pad subdues the track even further, moving across the track in slow, swelling arcs of dirty noise.

It’s a track that “hit between different tastes” for Kim and he was justified when he found various ”friends” from different musical backgrounds drawn to Urchin. The Urchin remixes gave Kim the chance to “work with friends I don’t usually work with” and from André Bravo’s hefty Drum n Bass attack, to Curtis Vodka’s cut n paste trip through the dense sounds of Jungle, it covers a vast section of left-field broken beat music.

Alternative urban electronic music

Urchin and its remixes, as well as the tracks they bookend, has found Kim on a new trajectory in his music. “I always chopped a lot of breaks on my sampler when I was younger,” explains Kim “but I didn’t try to make proper Jungle like I do now.” Kim’s earlier releases would favour the more familiar constructions of European House and Techno. It would always have that raw machine driven component, but it’s only in the last few years that he’s started to explore the broken sounds of Jungle and IDM in his own music.

I wonder if it’s a reluctance on the part of Norwegian audiences to embrace these sounds that has seen him avoid these sounds in the past. He’s unsure. Although he feels that “it’s getting more open for it,” this style of music it’s still more popular outside of the country, and it’s been like that for a while.

As a kid growing up, with a foundation in Hip Hop, Kim was attracted to IDM and the British wave of artists coming from the ranks of warp et al, but he hardly found any kindred spirits in his love for this kind of music. “Most of my friends growing up didn’t like this kind of music,” he recalls, “and still today don’t like this kind of music” he adds with a tapering laugh.

Kim refers to this kind of music as an “alternative urban electronic” music with specific ties to the UK. It has much more in common with Hip Hop than the European tastes of House and Techno and in it he’s found a familiar language in which he can adapt to his own musical voice. Built from breakbeats and what he calls “errors”, Kim’s process still starts from the same machine-driven origins it always has. A live-improvisational jam between modular synthesisers, guitar pedals and computers lay the groundwork, and he never knows what will come from these sessions until they emerge from the chaos.

Kim likes to refer to his music as “art by accident” and you can hear it in its rawest form on the “Tools and Tracks“ release on Kim’s Bandcamp account. Lately however these accidents have yielded results closer to his youthful musical indulgences, than pandering to the trends around him and it’s not just something that’s cemented around his love for the sounds of IDM or alternative urban electronic music, but it goes even further back to his roots.

Finding a community

Kim Dürbeck has come full circle in more than just one way over the last two years. On the one hand, he’s been tapping into this raw, primal energy from his youth, while on the other, he’s going back to his Vietnamese diaspora roots.

Kim grew up in Norway to a Norwegian mother and Vietnamese father. In one of the Jaeger mix sessions, he talked about digging through his parents’ old tape collection, which included some Disco from his mother and “sessions” his father recorded on tape during Kim’s childhood. What these sessions were however has always eluded us…

It was “mainly Vietnamese folk music. Cai Luong, inspired by Chinese opera, but more at home,” explains Kim. The senior Mr. Dürbeck “was doing sessions every weekend with his friends” and would sing and write music for tape. Sometimes he would record sessions with guitar and mic with a lot of echo, which Kim says remind him of “Acid House.” “Tuned in half tones, it’s very different,” he explains.

Kim spent his childhood immersed in these tapes, laying the foundation for a rudimentary grasp of the production and mixing process. He cut and spliced his dad’s tapes together in mixtapes, laying the foundation for sampling techniques and Djing later on. These early Vietnamese roots lay largely untapped for the most part of Kim’s musical career however. Besides the odd annual celebration – one of which gave him his first DJ gig, playing Trance – there weren’t many who shared Kim’s interests at that point. While a burgeoning community of Vietnamese electronic music enthusiasts were waiting in the wings, Kim was largely left to his own devices and justifiably gravitated towards the Trip Hop, Hip-Hop, Trance, House and then Techno that his Norwegian peers favoured.

That all changed with social media as he started to find a larger Vietnamese diaspora producing and proliferating electronic music. It started with a “meme-account” he created, but blossomed beyond Internet humour and into music as he sought like-minded people.

“Being a Vietnamese diaspora, you search for other Vietnamese diaspora,” says Kim. It was “interesting to see people growing up just like you – doing music and being alternative.” Today there is a large community, spread all across the world, and Kim is certain it’s “mobilised.” We met a portion of this community in November when Levi Oi and Mobilegirl came to play alongside Kim for Oslo World, but the community stretches further and can be traced all the way back to Vietnam today.

Decolonising the dance floor

Through this extended social media network, Kim soon found more people like himself; people of Vietnamese ancestry living in the west, making electronic music. Most notably it was the introduction to Nhạc Gãy that set Kim off on a path to exploring these sounds again and becoming a vital part of this community. Besides Nhạc Gãy regular Dustin Ngo contributing to Kim’s Urchin remixes, there is also Kim’s contribution to the first Nhạc Gãy compilation.

“Nước Mắm Is My Holy Water” is raucous ensemble of drum machines and a folksy Vietnamese samples. It’s the first time you hear these two aspects of Kim’s youthful explorations combined, and the results are as intriguing as they are surprising. “It’s electronic music with vocals,”explains Kim of what constituted those early Vietnamese influences. “That’s why it fits so well in my jungle track for the Nhạc Gãy compilation.”

It all enriches that “collage of genres” that Kim likes to tap into when he makes music. More than that, it sympathised with Nhạc Gãy’s objective to decolonise the dance floor, as a strictly Vietnamese electronic music. It allows “access to the locals without going through the west,” according to Kim, but at the same time it’s not something that panders to exotic tropes like a library record or tourist CD. These are Vietnamese voices making electronic music in a broad sense, covering “electronic music in all genres.”

From the Jungle-infused Acid of Kim Dürbeck to the blistering Techno of Attiss Ngo on the compilation, there isn’t anything like a specific style of music that identifies these artists and their music or their nationality. It spreads as far in electronic musical styles and genrs as the Vietnamese diaspora they count amongst their ranks.

Looking towards the horizon

Kim “was supposed to go there and play” with the “Nhạc Gãy people” and initially the Oslo world line-up was also to include them “but because of covid” that never transpired. “So we had to book people from Europe.” Levi Oi and Mobilegirl certainly represented the larger community in full force. It looks like any future plans will have to be put on hold again as we face another season of covid restrictions and measures, but Kim is hopeful to get out there soon.

He continues to expand that network of friends he’s making across the world, when he’s not at home making music and he seems to be always busy on that front, as this premiere can attest. Besides producing, he’s also performing live as part of an ambient/techno trio in Sandefjord, “keeping the community alive” in the small town. He is also about to launch a new label with Larus Siguvrin, and Patås called Lek Rec, which will see the first releases come to the fore next year. At the same time he is currently working on the second remix package for Urchin while a hard-drive somewhere is bulging under the weight of music he’s created over the past two years.

As our conversation draws to a close, he excitedly tells me he’s “found a movie about Vietnamese Moroccan diaspora, and they have a very cool way of talking, mixing Arabic and Vietnamese.” …. “And just the thought of this is inspiring when it comes to music.” It will be curious to hear how this might develop and only time will tell.

There’s still clearly a lot more on the horizon for Kim Dürbeck; too much mention in a paragraph really, and it seems the pandemic has seen the artist hit a new stride, especially in music. He’s not only found a new perspective going back to the sounds of Jungle, but also a way to honour the sounds of his Vietnamese roots. From his tapes to those urban UK sounds, Kim Dürbeck is a melting pot of ideas at the moment and it seems to have no end.