What have the futurists ever done for us? Well, they might have invented Techno. Ross Bicknell writes about how an early 20th century art movement might have influenced, or at least in some part inspired today’s club music.

1. No work without an aggressive character can be a masterpiece.

2.Time and space died yesterday. We already live in the absolute, because we have created eternal, omnipresent speed.

3.We will glorify war,.. the world’s only hygiene.

4.Destroy the museums, fight moralism, feminism, ..utilitarian cowardice.

5.Sing the vibrant nightly fervour of arsenals and shipyards blazing, bridges that stride the rivers like giant gymnasts, flashing in the sun with a glitter of knives.

These are a few choice slices from the 11 point manifesto of The Futurists, an Italian art cultural movement lead by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. These excerpts were printed on the front page of a popular French newspaper, Le Figaro in 1909 and caused a bit of a stir. They barely even printed political party manifestos back then, let alone the ramblings of artists, so this might point towards what a big deal they were considered to be.

Marinetti & the Futurists flirted with Fascism. He was ideologically opposed to the Marxist idea of class struggle and was elected to the Fascist party’s Central Committee in 1919 after Italy’s disastrous and humiliating part in WW1 representing the Allies. Mussolini had a great admiration for Futurism and Futurists paid him back by engaging in propaganda and violence in his name.

So why discuss these fascistic, war hungry rent-a-mob? What have they ever done for us, and what have they got to do with electronic music as we know it?

It’s because their belief in and celebration of mechanised society e.g. boats, trains, plains, modern agriculture, motorways, telephones and the city being a force for positive change. The Futurists believed that these trappings were a force for speeding up time and signalling a new, more desirable consciousness that did away with the ‘pensive immobility, ecstasy and sleep’ of previous generations and their literature and art. Instead they intended to ‘exalt aggressive action, a feverish insomnia, the racers stride,.. the punch and slap’. I think they got their way and very tiring it is too being part of it all. (I’m old now). Ok it’s exciting too. The undoubtable celebration of speed, volume and power as progress in society throughout the 20th century has its many echoes in arts, music and culture, from 5.1 cinema sound-systems allowing an attack helicopter’s missile to whizz about the room and detonate at the base of your spine, to electric guitar solos crackling through a speaker stack hanging from a 200 metre high scaffolding in a mega-arena, to industrial samples and distorted Hoover bass lines shaking the floor of nightclubs across the world and being simultaneously broadcast onto millions of pocket digital devices.

We can take the pre-internet days of the early 1990s as the land before time sped up exponentially, it had an impact rather like the effect of the monolith in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 and pretty much the same year (woah…) The Industrial revolution, especially trains, had the same seismic effect. Futurists sought to celebrate a move beyond art being about communities loosely based around farming, so to keep up basically. Such ye olde existences have been celebrated/revisited by various art/music movements (think Dylan, folk revival, ambient, minimalism) in a distinctly non-futurist manner throughout the 20th century in music. It took a while for the musos to catch up. The idea of the past as slower, more spiritual, humane place or time still underpins many a political belief or music preference. William Blake’s Dark Satanic Mills referred to an almost Mordor-like future brought about by industrial destruction of the past/nature. Plagues, volcanoes, floods, cats and dogs living together, you know the score. Biblical shit.

These have all come to fruition in our collective consciousness in the 20th century, as has the Futurist’s wish/premonition of mechanised war. The relatively fragile human body in which we are still irritatingly encased (for some, take note 2046 transhumanists, the super-rich wannabe cyborg immortals. https://youtu.be/vqkddbl1HCY) has had a fair few knocks in this period and been subjected to the horror machines can elicit. The Futurists were well up for this and it seems humans have an increased need to engage in this dance with the machines that can seriously fuck them up but also I guess make things work well with central heating and stuff.

So let’s get back to the question, what have the Futurists ever done for us?

Erm, they channelled the excitement of the times? Ok, ok, yes, yes, I suppose I can’t argue with that. But what else?

Erm.. One may argue that they invented the aesthetic of what was to become the future? Ok clever clogs, I accept that this may be partly true in an ideological sense, but in pure aesthetic terms it would have to be shared in no small part by writers of popular science fiction and their book cover designers. Ha.

They invented the future, period. Erm, you’ve lost me, but perhaps in terms of music you might have a point… But what have the futurists ever really done for us? They invented Techno? Oh right, yeah that is pretty good.

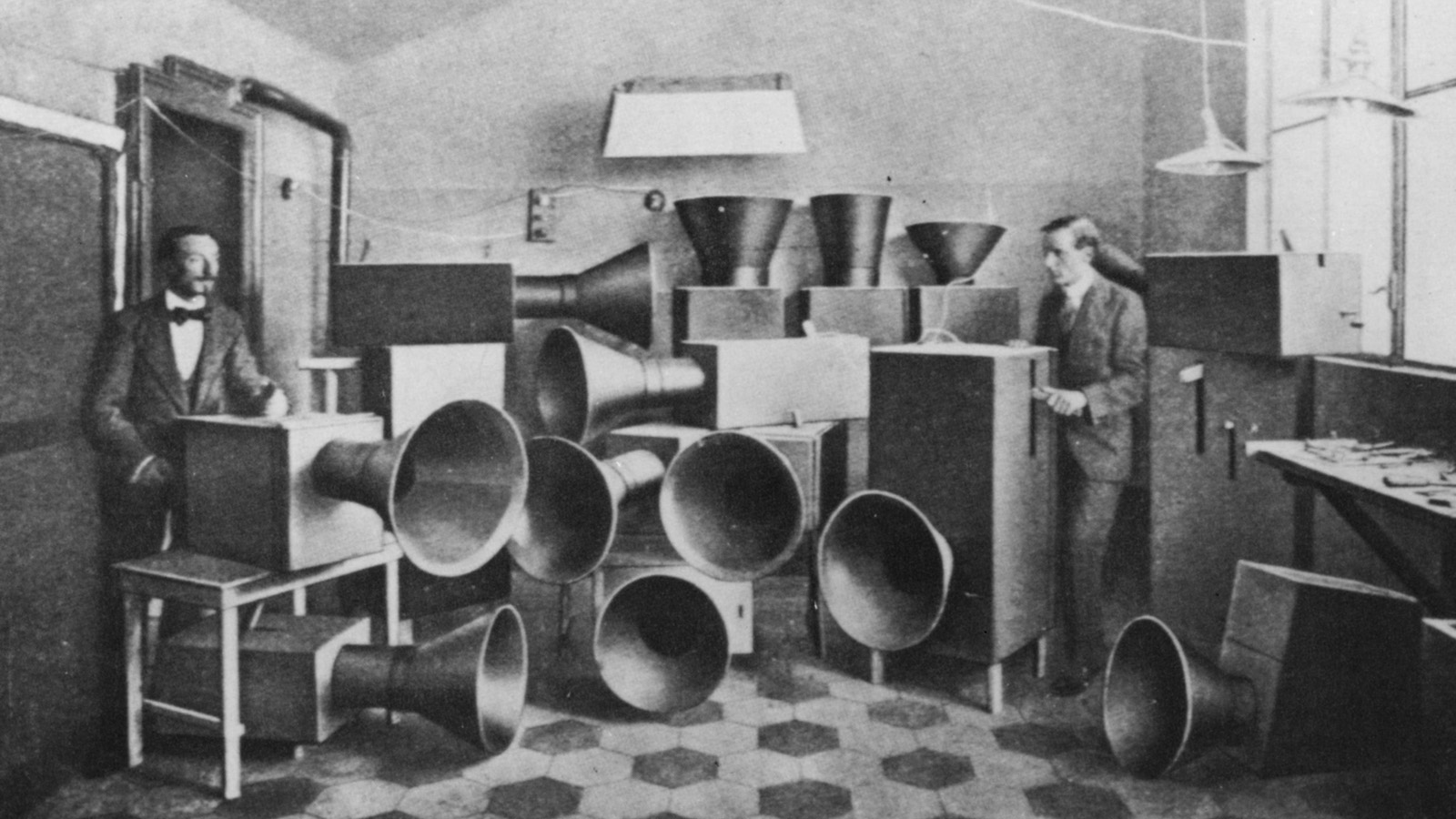

In his piece, The Art Of Noises: Futurist manifesto (1913), Luigi Russolo concludes that futurist musicians should substitute for the limited variety of timbres that the orchestra possess, the infinite variety of timbres in noises, reproduced with appropriate mechanisms. He identifies 6 families of noises. Among these are crashes/thunderings, whistling/hissing, murmurs/whispers, screeching/creaking, bangs on metal/wood, voices/shouts/noises of animals and people. He sees this as an antidote to orchestral music. ‘Do you know of a more ridiculous site than that of 20 men striving to redouble the mullings of a violin?,..let us drink in, from beat to beat, these few qualities of obvious tedium, of monotonous impressions and cretinous religious emotion of the Buddhalike listeners, drunk with repeating for the thousandth time their more or less acquired and snobbish ecstasy. Away!’ So it’s fair to say he wasn’t a fan of classical music.

To be honest the idea of working mechanisation into music was a not a huge leap of the human imagination (if such a thing is ever actually possible, discuss). It was underway in other artworks, but nobody had done it, or at least written about doing it, in 1913. He created an instrument to demonstrate how it would come into use, a mechanised noise box, which used sounds of industry and those mentioned above to create musical works. It was about the abandonment of the 12 note scale completely and the pursuit of a music which featured the organisation of different timbres above all else (sound like anything we’ve heard?) These timbres were evocative of the industrial age, and a brand new future, as digital blips, beeps, shash and industrial sounds were to evoke the coming age of the technosphere for techno artists. There are few surviving recordings of this machine sadly but musicians who it has been claimed are directly inspired include Pierre Schaeffer and other Musique concrete artists, and also Stockhausen. The lineage is also clear to see throughout the 1900s as John Cage questions what constitutes music still further by releasing ‘4.33’ and leads into the minimalists Steve Reich and Philip Glass et al. Their stripped down build the house brick by brick/take it down again musical experiments and works contain blueprints for electronic music as we know it. Fast forward a few decades and you can hear their influence in Derek May’s Strings of Life from 1998, Orbital’s Kein Trink Wasser (1994) and many others.

In my mind the most intense characterisation of the Futurist’s overall ideological aesthetic thrust is techno, which came into being in the 80s in Detroit (via Germany and New York also). A key figure and member of one of Techno’s founding labels Underground Resistance, Jeff Mills, has explicitly said that it was meant to be a futurist statement. Techno differs from the fascinations of Industrial music, in that the futurist philosophical standpoint is highlighted. Also the commitment to Russolo’s and the Futurist’s wider ideas like the romance of speed and mechanised violence seems more absolute. Techno was an unspoken decision, a manifesto if you will, with disciplines and rules that must be broken as well as those that must be kept to. Either inadvertently or directly, the reference to the futurists is unavoidable. Jeff Mills in fact cites Alvin Toffler’s book, The 3rd Wave, a futurist treatise from 1980, by which time futurism was a genre or a thing, and much had been published in connection with the term. Toffler describes a high-speed revolution, much like the Italian Futurists did, but he describes the subsequent one, which I guess we can call the digital revolution. In Toffler’s preface he wishes to make clear that he does not wish to dwell on the costs of change, but emphasises the costs of not changing. His previous book Future Shock focuses on the former. Tellingly Techno chose to cite the latter perspective. I’m afraid that’s it for references to the book Jeff Mills actually cited. Complain all you like, I don’t care, that’s it, final. I’m sticking to the Italians.

So is techno a true futurist statement? And what does that mean? Pure techno’s seminal tracks share playful experimentation with a commitment to a sparse, driving, industrial aesthetic which restricts itself to infinitesimal change alongside a framework of a constant musical trope. This is the high-energy kick drum/hi-hat combo, which categorises a large degree of dance music. It requires a certain level of commitment to listen/dance to when at the speeds featured in techno (usually around 127-140 bpm) and with its mechanised timbre. It asks listeners to embrace the energy and come along for the ride, rewarding with the satisfaction of noting the episodic or gradual affectation of the synth/sample/beat/percussion elements that circle around its central structure. The high pace seems to remove the desire to look back at what has just been, as there is rarely a chance to do so, the experience being pretty intense. You are being urged forward and it is taking energy to stay focused and inside the box, a bit like a sport. If you do keep up with every mini event and stay for the increasingly frequent culminations of events and energy, then a feeling of cerebral and corporeal oneness with this hyped energy is one of your rewards. At the heart of techno (if thy tin man hath a heart..?) I see an indifference to and thus a rejection of, well what,..hmmm, I’ll have a go.. 1. Melody = soul. 2. Chord structure = romance and 3. Pining lyricism = individualism. In this re-prioritising of the sanctity of the individual in the musical experiences involving techno lays some parallels with the Futurist’s train of thought. Mechanical brutality is romanticised (ironically) as bodily fragility is scorned and cast aside, a member of the collective can suffer and die.

And there are some literal interpretations too: Marinetti for instance even has a rant about being in a car and how damn sexy it is to nearly die as it crashes into a ditch. ‘Maternal ditch, almost full of muddy water! Fair factory drain! I gulped down your nourishing sludge..’ Ha ha. It’s easy to laugh, and I hope you do… but I don’t remember laughing much reading JG Ballard’s 1973 update on the theme Crash, with the pokey early 1900s language replaced by cold psychosexual prose fusing arousal, death and violent injury together in a tempestuous and seductive gridlock of depravity. Ballard narrated futurisms with an eye colder than that of the Futurists; the dispassionate observer nevertheless needed a whiskey every hour, on the hour to hone a numbed effect enabling him to write it. He had lived through WW2; the Futurists hadn’t, by the time the manifesto came out anyway.

Gary Numan managed to have a bit more fun with the same subject matter in his techno-pop smash-hit, Cars (1979). You can hear the echoes of Ballard and thus Marinetti in recent releases such as those by many EBM artists, Silent Servant and Broken English Club’s ‘Wreck’. It’s safe to say that unlike ‘Cars’ this will not be a pop smash hit. There’s a video for this song which features disaster-porn like footage of the coralised remains of the Titanic which itself was a Futurist’s wet dream. You can indeed see that it is very wet, but more like a nightmare, mischievously glamorised by the saturated neon pink and yellow filters that have been applied with sloppy, liberal glee…

…To be continued