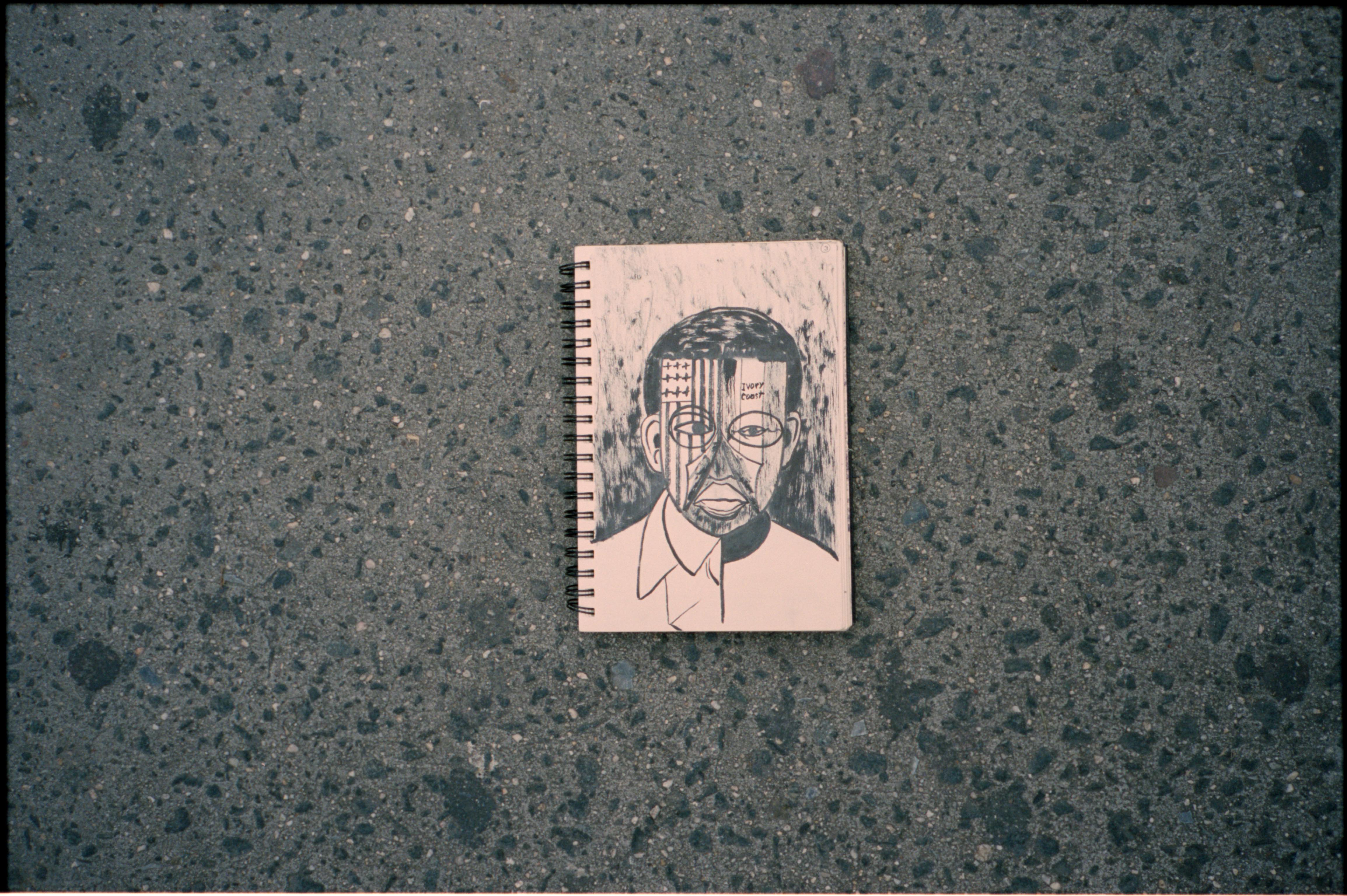

There’s something intimidating, yet captivating about Baya’s new double EP, “Oslo – Harlem” before you even get to the music contained within. Even just sitting on the shelf, the artwork provokes with the audacity and virility of its imagery, the African mask in all its magnificent presence. It touches on something visceral and primordial in the viewer. It carries with it a weight that’s intrigued artists for centuries; from Picasso to Jim Carrey the mask has been decoded and deconstructed time and time again to reveal layers of incredible depth that unfolds as much through the viewer as it does through its own physiognomy. It’s quite bold to the point of being almost menacing, but there’s no one aspect of its being that should provoke. It’s a feeling a young Andrew Murray (Baya) too can relate to from the time when he was first introduced to the vision of the African mask. “As a Norwegian kid you’re like ‘what is this’”, says the young Norwegian artist over a coffee at Bare Jazz, and what made his first encounter more significant than any other was that this was not to be just an ordinary mask viewed in the context of a museum or a gallery but rather a creation of Andrew’s father, Bruno Baya Sompohi’s. So to know the story of “Oslo – Harlem” we must familiarise ourselves with Bruno Baya Sompohi’s story first…

A talented young artist from the Ivory Coast, Mr. Sompohi found himself in Rome and then Bergen on scholarships to study sculpture in the eighties. It was in Norway where he would have the significant encounter with Caroline Baardsen that brought Andrew into the world, but it’s also here where he expounded on his lifelong work; delving into the concepts of the African mask through a thoroughly western image.“He found the African mask at Sagene kirke”, explains Andrew, “where he saw the mask in the church door, and he saw the parallel between the African mask and western society.” He calls the concept Gla, shortened from Glalogy. “Gla is the manifestation of the African spirit tradition, African society”, explains Mr. Sompohi during an interlude on Oslo-Harlem, his voice a rich mixture of French accentuation and a booming African tenor. “Gla is the music, Gla is the fine art, Gla is the everything” and the artist focuses all these elements through the aesthetic of the African mask. Visually, the results are striking works of immense proportions with concepts that go deeper and deeper with each idea revealing the next in conceptually dense works of art with the mask as foreground. “There’s always something” says Andrew of his father’s work, work that’s consumed “45 years” of the artist’s life, which Andrew feels he has barely scratched the surface of.

A talented young artist from the Ivory Coast, Mr. Sompohi found himself in Rome and then Bergen on scholarships to study sculpture in the eighties. It was in Norway where he would have the significant encounter with Caroline Baardsen that brought Andrew into the world, but it’s also here where he expounded on his lifelong work; delving into the concepts of the African mask through a thoroughly western image.“He found the African mask at Sagene kirke”, explains Andrew, “where he saw the mask in the church door, and he saw the parallel between the African mask and western society.” He calls the concept Gla, shortened from Glalogy. “Gla is the manifestation of the African spirit tradition, African society”, explains Mr. Sompohi during an interlude on Oslo-Harlem, his voice a rich mixture of French accentuation and a booming African tenor. “Gla is the music, Gla is the fine art, Gla is the everything” and the artist focuses all these elements through the aesthetic of the African mask. Visually, the results are striking works of immense proportions with concepts that go deeper and deeper with each idea revealing the next in conceptually dense works of art with the mask as foreground. “There’s always something” says Andrew of his father’s work, work that’s consumed “45 years” of the artist’s life, which Andrew feels he has barely scratched the surface of.

Andrew’s familiarisation of his father and the work has only been a recent occurrence, because Before the birth of his son, after a “racial incident” in Norway, Mr. Sompohi “had to leave the country”. From there on in, he and Andrew’s relationship, would be a strained, distant relationship, mostly conducted over the phone. “It wasn’t the right way to build a relationship” says Andrew regrettably as he recalls his father’s “dark african voice” over the phone, a strange intimidating thing to a Norwegian adolescent growing up in the suburb of Bærum.

Not fully aware of his father’s work and having only a distant, almost estranged relationship with the patriarch, Andrew would embark on a journey towards a musical career almost by accident, without realising he and his father “had the same thing in common”. Andrew’s introduction to music would come in the form of his “neighbour playing ‘Sweet home Alabama’ on his guitar” and from there Andrew would nurture his musical voice through the that same stringed instrument with a penchant for the “heavy stuff” from the likes of “Iron Maiden and Turbonegro” at first; tastes that would evolve and mature with the artist. The unlikely setting of Bærum would prove to be a perfect environment for the gestation for an artistic personality, and like Kai Gundelach, Hubbabubbaklubb and Skranglejazz, Andrew Murray would turn to music as a direct opposing reaction to the stereotypical “Bærum, rich man’s blues” individual and the stereotypical sport-enthusiast conservative personality it nurtured. “That in combination with the fact that you are from Bærum and do have the means to buy you your first guitar” seems to create a most fertile environment for the artist to spring into existence. From the heavier stuff, Andrew would move into Jazz and beyond, spending “every second Friday, buying records from George Benson, Jimmy Smith and Miles Davis” not five foot from where we sit for our interview, before heading off to Jæger across the road to experience electronic music in its natural habitat.

While Andrew was in the mitts of informing a vast musical dialect through the experiences of Bærum, the guitar, heavy Rock, Jazz and everything in between, Bruno Baya Sompohi was also on a journey of new discoveries of sorts; relocating to Harlem and establishing a family in his new home. “I gathered when you are different and curious you’ve got to see the world” surmises Andrew about his father’s relocation to the cultural “melting pot” that is New York. After a few years and staying in touch with his father, and more importantly getting to know his siblings, Andrew too eventually decided to visit Harlem not particularly to visit his father but rather to visit the siblings that he had never met in person, people that shared this “common link” through a father, but whose own relationship, shouldn’t necessarily be dictated by it. “I wanted to meet them” thought Andrew, “and at the same time, let me meet my dad.” There are a lot of people that “share a similar story” according to Andrew, people that form part of “the third culture kids” phenomenon and he set off on his mission in a very objective manner. “Let me be open to this”, he thought “and not get too personal, because this is how the world is moving forward.”

The “consequence as an artist” for Andrew and what would become his artistic moniker Baya was “the most real thing that’s ever happened” to him, a very personal experience that would shape his musical identity irrevocably and formed the basis of Oslo – Harlem. It was through his father’s work and the resulting interviews Andrew conducted with his father about his work that informed the vague conceptual framework for the music that followed.“I need to have this in my music”, recall Andrew of those experiences. What was intended to be a just a meeting of father and son for the first time, became a meeting of one artist to another. A “common interest” then lead to a collaborative work, where Mr, Sompohi’s visual works work would inform and play counterpoint and accompaniment to the younger Baya’s musical work.

The result is Oslo – Harlem, a double EP in a versatile musical dialect that explores the notion of contemporary pop music through a more adventurous sonic palette that has been coined “experimental” by more conservative media outlets. Oslo – Harlem is a musical collage made up of contrasts and chance encounters between disparate musical sonic structures, funneled together as one distinct musical dialect through the artist at the centre of it. Andrew uses the image of his studio to explain his creative methods. Between one “wall of guitars and another adorned with synthesisers” Andrew’s music as Baya finds a perfect balance in the middle. “Everything is a combination, it’s combinations that I’m playing with” muses Andrew. Even when I pick up an African identity in his music through the polyrhythms in his music, Andrew is hesitant of confirming it as a “parallel that’s genetic”. It’s more likely to be just another combination of various disparate influences, rather than an African heritage he downplays as something distant he doesn’t have any relationship with yet. “I’m as white as Olanskii down there” he considers with a dry chuckle as he points across the road to Jæger.

Like Mr. Sompohi’s work that finds this parallel between western society and the African mask, Baya’s music draws parallels between various aspects of music and of course the theme of the mask through Oslo-Harlem. “I’m excited for this record to have this face” says Andrew of this visual element to the album. It will also be a theme running through the live shows I learn, as Andrew collaborated with his father and Red Bull to create masks that will form the backdrop to the stage, an experience Andrew quite “inspiring”. “It was like going to art school for a week.”

Like Mr. Sompohi’s work that finds this parallel between western society and the African mask, Baya’s music draws parallels between various aspects of music and of course the theme of the mask through Oslo-Harlem. “I’m excited for this record to have this face” says Andrew of this visual element to the album. It will also be a theme running through the live shows I learn, as Andrew collaborated with his father and Red Bull to create masks that will form the backdrop to the stage, an experience Andrew quite “inspiring”. “It was like going to art school for a week.”

Andrew shows me a video of the masks, verbosely colourful statuettes that peer at you with some intensity accentuated by the colourful lights that frame and possibly softens, o humanises their bold appearance. It’s an aspect to Oslo – Harlem and the succeeding live show that emboldens the musical narrative, not in terms of a defined single concept but rather a concise musical and visual aesthetic that influences each other. And although it’s quite a pronounced at this stage of Baya’s music, it might also just be a fleeting thing. “It’s something that might only be this record” suggests Andrew. “What’s fascinating for me now is that it feels like the first layer of an onion has been peeled off” says Andrew. As he evolves as an artist, Baya is certainly to make quite an impression perhaps even as much if not more than the elder artist of the same name.

It’s unclear whether he and his father will be working together more in the future, and Andrew is already suggesting that he intends to “move on” from this into his future works, but there certainly is a parallel there that looks to perhaps inform the further development of Baya s a musical artist.

*For more on the artist, follow Baya here.