New York in the seventies was an unimaginable mixture of artistry and dissolution coming together in one the most vital era’s for popular music. It was a period of great economic stagnation, urban decay and poverty, elements that can make a great Petri dish for new creative minds to flourish. People that pushed at the edges of convention and taste in their pursuit of unadulterated and free form of expression became the city’s new inhabitants and formed the basis of so many new movements in art and music that were incredibly influential in today’s landscape and are often taken for granted. I’m not sure what is it about a society in decline that inspires and nurtures creative movements like these, but like Berlin in the fifties and Detroit in the eighties, New York in the seventies has a hotbed of ingenuity and imagination that not only inspired individuals, but also bred entire genres. In music alone those genres include Hip-Hop, Punk, and of course Disco. Today Disco might elicit the addition of “sucks” when mentioned, but before it became overrun with Swedish pop sensations, falsetto male vocals and cocaine habits that would make Elton John blush, it was something far more significant, not only in the discourse of music, but in the socio-political landscape of the seventies in New York and perhaps even further afield to the point where it’s impact is still relevant today. This is not going to be a biography on Disco however, since if that’s what you’re looking for, the minefield of false starts and opposing rhetoric will leave you in the middle of no man’s land, staring at a mirror ball through Bootsie Collins’ star studded sunglasses. You can pick and mix your own history of Disco, depending on your perspective, but there are three significant developments in Disco that are probably the most important to our story today when we trace back the idea of the DJ, the Club and the Sound System. It all goes back to New York in the seventies and four specific venues: Sanctuary, The Loft, Gallery and Paradise Garage, which incorporated names like Francis Grasso, David Mancuso, Nicky Siano and Larry Levan as fundamental orchestrators for what we’ve come to know as club culture today.

It existed not so much out of a chronological sequence of events with each establishment and player occupying a position on the timeline, but rather more of group of events that sprung to life independently out of the same circumstances with very little to no influence on the other. What would eventually become known as Disco, was never really called Disco until the media classed it as such with the arrival of pop sensations like Donna Summer and venues like Studio 54. There was something called a discotheque but even that’s as fluid as the Rivers of Babylon and the discotheque wasn’t really even that… it was in fact a loft apartment. Yes, although Sanctuary was strictly speaking the first in the chronological order of events, what would become known as Disco – and we’re the talking the underbelly of the genre; the thing that spawned it all and has no relation to any other aspect of Disco; the underground that never bubbled even close to the surface – would be David Mancuso’s Loft parties. Mancuso, who has always described himself as a “communal minded-person” set up the Loft parties in the early seventies as a venue to bring together people from all walks of life through music and informal gatherings in the context of a rent party taken to the extreme. It wasn’t a club, which in those days required a membership, nor was it bar, since no alcohol was served there. It was first and foremost his home, the place he would “eat, sleep and dream”. It was a place you could have a meal and a place where you could leave an IOU instead of the usual two dollars in rent contribution, and never be expected to pay it, but you’d pay it, because of the principle of it all. But first and foremost, it was a refuge for the liberal music enthusiast where s/he could look another individual in the eye as an equal, regardless of a disproportionate social standing as dictated by the conservative norm. When you “mix economical groups together, you get social progress” according to Mancuso, a quote that he’s echoed through countless interviews through the years. Off the back of the Civil Rights movement and Stonewall in the late sixties this is a significant moment in club history. During a time when minorities were being persecuted for being black, Latino and gay in New York there wasn’t much room for people or any person in these categories to express themselves freely without serious repercussions from the authorities who still deemed these actions as illegal and sneered at them from their obtuse ideological soap boxes. Even the very recent Stonewall riots, which saw a series of spontaneous, violent demonstrations by members of the gay (LGBT) community against a police raid that today remains the catalyst for the gay liberation movement, didn’t change much on the face of it back in the seventies with the LGBT community still not truly free to express themselves in public directly after. Instead they sought safe havens through nocturnal activities, and they found that in places like the Loft, and Sanctuary, which coincidentally reflected it’s attitude in its name.

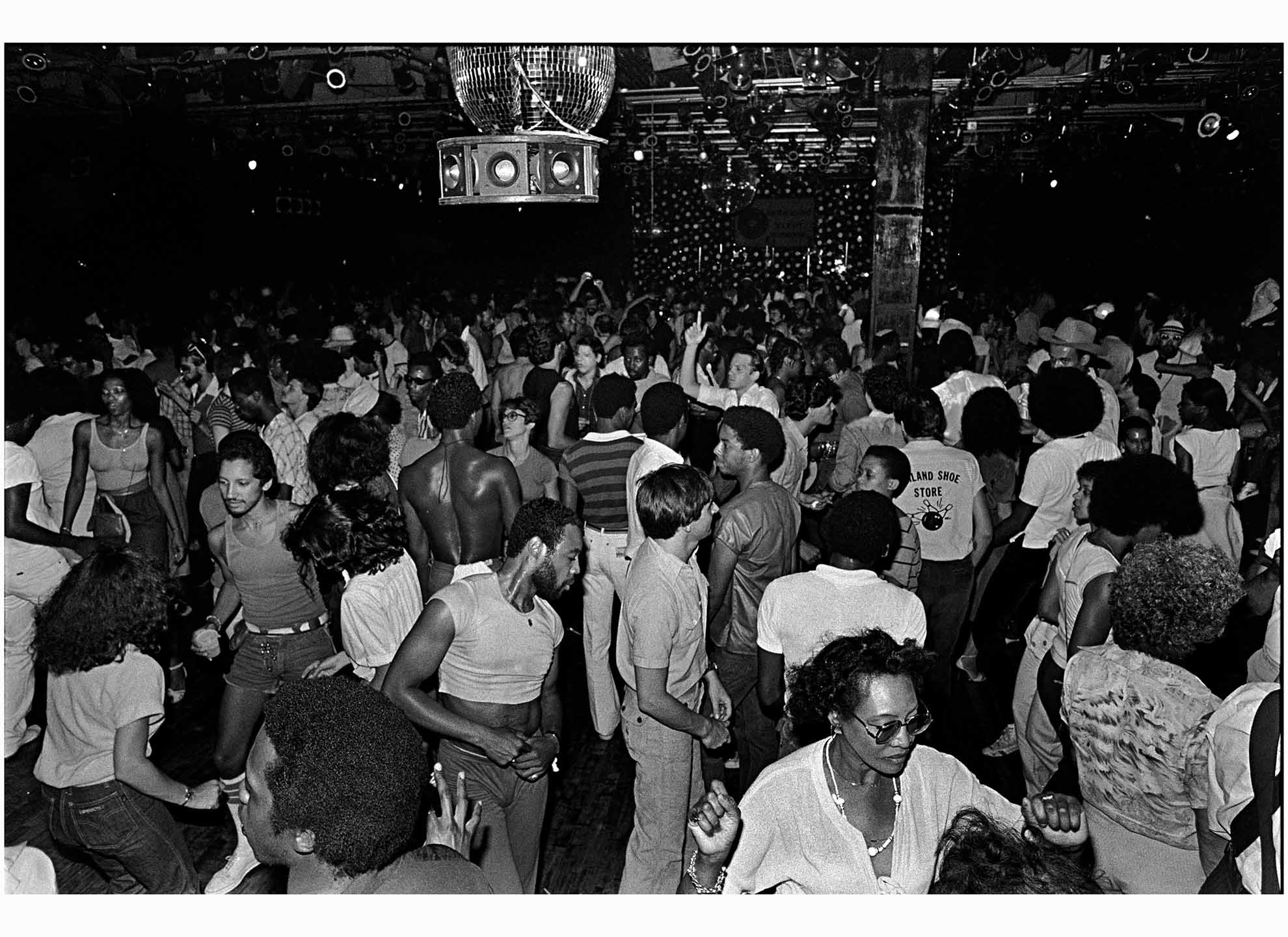

While The Loft came after the Sanctuary there was never any direct influence of one on the other but rather two independent institutions that sprung to life born out of the same social circumstances. There was however a direct interaction between the two with Mancuso having visited Sanctuary and many of the latter’s patrons often finding themselves at the Loft after hours, including on Sanctuary DJs and one very significant actor in the story of the DJ. His name was Francis Grasso, and although names like Steve D’Aquisto, Nicky Siano and Larry Levan would effectively follow in his footsteps, it was Grasso who would be the first person we’d know as a DJ in today’s terms. He would be the first person to segue two records together, beat-matching them to create a single undisturbed piece of music with records that come together to create a unified feeling. The music Grasso was playing was not Disco. “You had Booker T and the MG’s, you had Sam and Dave, you had your Memphis sound, had your Detroit sound, the Motown Sound. You had to mix it all up”; says Grasso in an interview with Frank Broughton. Even Rock would not be out of bounds with Grasso sighting Led Zeppelin’s Immigrant Song as a personal favourite to play. Grasso, like everybody at the time, was playing 45’s, the little 7” singles that had a about 2 minutes of music on it and required a lot of work from the DJ, but he still managed to invent the skill of mixing as we know it today, even though some might question the legitimacy of his claim that he could do it right from the beginning of his career. He was the first person we would recognise as a DJ today, but unlike many modern DJs, who seem very disconnected from their environment, Grasso was truly ingrained in his. He came from dancing to moving behind the decks and when he played it was all with one purpose in mind, getting the people on the dance floor. Sanctuary was a gay club that was a direct result of the Stonewall riots, after the original Sanctuary, a prominently straight club in an old church, made room for the first gay bar with a DJ in the world. New York was probably one of the most progressive places for gay rights in the seventies at a social level at least, and places like Sanctuary and Mancuso’s Loft were the venues that orchestrated much of this liberal attitude in the context of music. They were a refuge for young, black and Latino gay men “breaking their backs on the dance floor”; says one anonymous commentator in the documentary Maestro. The only intimidation came in the form of your peers and their ability on the dance floor it seems. It was an evening’s entertainment where the focus would not be on the DJ, but rather on the people on the floor. They, the dancers would create their own entertainment, and the DJ was merely the facilitator.

During this time the focus also turned to another important aspect in club culture. It was an element to the atmosphere that went mostly ignored, but soon turned out to become a fundamental element of the clubbing experience. No, it’s not the drugs – that’s a story for another time and an entire book in itself – it’s the sound system and the way we understand its role in the club today is a direct result of the seventies new obsession with sound in New York. For David Mancuso it all boiled down to “listening to the music like the artist intended”, but like everything else during this era it was indicative of a contemporary universal focus on sound quality that had also made it’s way into Sanctuary thanks to a Mr. Alex Rosner, who would also later go on to work with Mancuso to develop the Loft’s home system into a full-blown legendary club system like no other. “You don’t want to hear the sound system, but the music” was David Mancuso’s mantra. “He put the Klippschorns in such a way” recalls Nicky Siano in Last night a DJ saved my Life, “that they put out the sound and reflected it too, so they covered the whole area and exaggerated the sound.” This was when the Loft was in Princess street, it’s second, bigger location, and Nicky Siano, a mere teenager at the time was already a DJ and would party there alongside other young gay men like Larry Levan and Frankie Knuckles. The Loft would be a major influence for Siano’s Gallery, which opened in ’71 as a seventeen-year old Siano’s commercial answer to the Loft’s appeal – a space where counter-culture can thrive. By the mid-seventies there would be up to 200 clubs thriving in New York, many of them a direct descendant of the Loft’s influence and with this rise in popularity of the definitive club, came the rise of the DJ too and what Francis Grasso set out to do through beat matching two records eventually spilled over into the record industry and with it came three fundamental developments in club music and the music industry; the remix, the 12” single and the DJ-producer.

Very early on with the advent of the DJ came the record industry’s realisation of DJ’s promotional ability, with David Mancuso’s record pool, an organisation that bridged the gap between the DJ and the industry, aiding in the development of the DJ’s influence on recorded music. It didn’t take long for DJ’s like Larry Levan, Danny Krivit, Walter Gibbons, Shep Pettibone and Francois Kevorkian to require more than what their limited 45 7” records had to offer. An extended break, a introduction that went just 4 bars longer was something that would have not gone amiss in the DJ’s toolbox and with the advent of affordable reel-to-reel recording and the ability to print them straight to vinyl thanks to the close partnership between DJ’s and the record industry the remix was born. Although it was technically an edit rather than a remix and the first remix is actually attributed to Tom Moulton – not a DJ, but rather a producer and dance music enthusiast – it set about tracks that extended their three-minute average to 8/10/13 minutes. With the longer tracks and the audiophile-nature of music at the time came the need for a new format since the 7” could not reproduce the remixes to the extent that the DJ required and with that the 12” single was also born almost instantaneously.

In the context of the significance of the Loft, Gallery and Paradise Garage which also sprung into existence around the same time, with Larry Levan in the booth, these quite significant developments in the story of the music we’ve come to know as club music are still mere footnotes. It was the characters and institutions more than the developments that would make this an important time for music and like David Mancuso and the Loft, Larry Levan and Paradise Garage were key players in this story of Disco and club culture. So significant would Paradise Garage’s influence be here that it would even attribute the latter part of its name to a new style of music known as Garage. Not to be confused with UK Garage, which came much, much later, this New York version thrived in a raw passionate version of Disco that favoured longer edits and a higher energy that catered to their predominantly black, and Latino gay clientele. It had all the ingredients that defined Disco: a mixed audience, an impressive sound system, and a DJ that provided a segued music experience for an entire night, and this DJ, like Mancuso, Grasso and Siano is regarded today as one of the legends of the DJ world. Larry Levan came at a time when Disco was at the height of its popularity as an underground culture and in some ways he, alongside Frankie Knuckles provided the stepping-stone from that genre into House. “He got behind the turntables like he was always meant to be there” says Nicky Siano in one interview about the rise of his protégé, Levan. It would actually be Knuckles who introduced Larry to Nicky, and although the latter taught the former everything he knew it would be Levan, through raw talent, that would develop the music further than anybody before him and would make Paradise Garage the legendary institution it is today. It’s no coincidence that so many DJs, including Prins Thomas and Pål Strangefruit here in Oslo would reference the Garage as an influence, even though they were on the other side of the world at the time and had never come in close physical contact with it. Larry Levan and Paradise Garage took the music into new territories, based on those fundamental aspects set forth by the loft, Mancuso and Grasso, while pushing at the boundaries, with Levan specifically making his mark as one of the first DJ-producers alongside names like Tee Scott and Walter Gibbons. Levan’s affect on his immediate contemporaries like Danny Krivit and Tony Humphries is undeniable and with DJs like these and Knuckles taking Disco from Garage to House, there is an unbreakable thread that worms it’s way right through the present day.

Stories of the DJ’s sets, the club and Richard Long’s sound system are today legends in their own right, but in many ways Paradise Garage also spelled the beginning of the end for this underground counter culture. When the venue started splitting events in to gay and straight nights, Mancuso’s vision of a mixed social group was lost and when the AIDS epidemic reared it’s ugly head, club culture took a significant blow with this club at the centre of it all. When the disease eventually consumed the proprietor Michael Brody, the closing of Paradise Garage was somehow also symbolically the death knell in Disco’s coffin, aided in many ways by the commercialisation and hedonism of the music that was introduced by the likes of Studio 54. But that’s another story altogether, another parallel timeline in the story of Disco and it’s something that definitely tarred Disco’s reputation beyond some. That’s also not the legacy of Disco. No, Disco’s legacy today is an immersive sound system, a mixed crowd and DJ providing a continuous stream of music for everybody’s listening and dancing pleasure. Disco’s legacy is also the 12” single and the remix, but it’s also about giving counter culture an opportunity to thrive. When you walk into a club today and a sound system greets you with a warm fuzzy feeling inside, that’s Disco. When you hear one of your favourite tracks extended through another, that’s Disco. When you hear a DJ playing a different version of a familiar track, that’s Disco. When you stay on the dance floor the entire night and your dancing-neighbour, who is from a completely different cultural background, has never left your side, that‘s Disco. In light of recent the events surrounding the killing of two black men in Dallas and Baton Rouge, and the mass killing at a gay Florida nightclub, it’s more important than ever to remember what Disco actually was and what it’s legacy is today even in its socio-political context too. Disco was always more than just the music, and even though some of us, this writer included never go to experience it in it’s original form, we are still living the legacy of Disco every time we step out onto the dance floor.