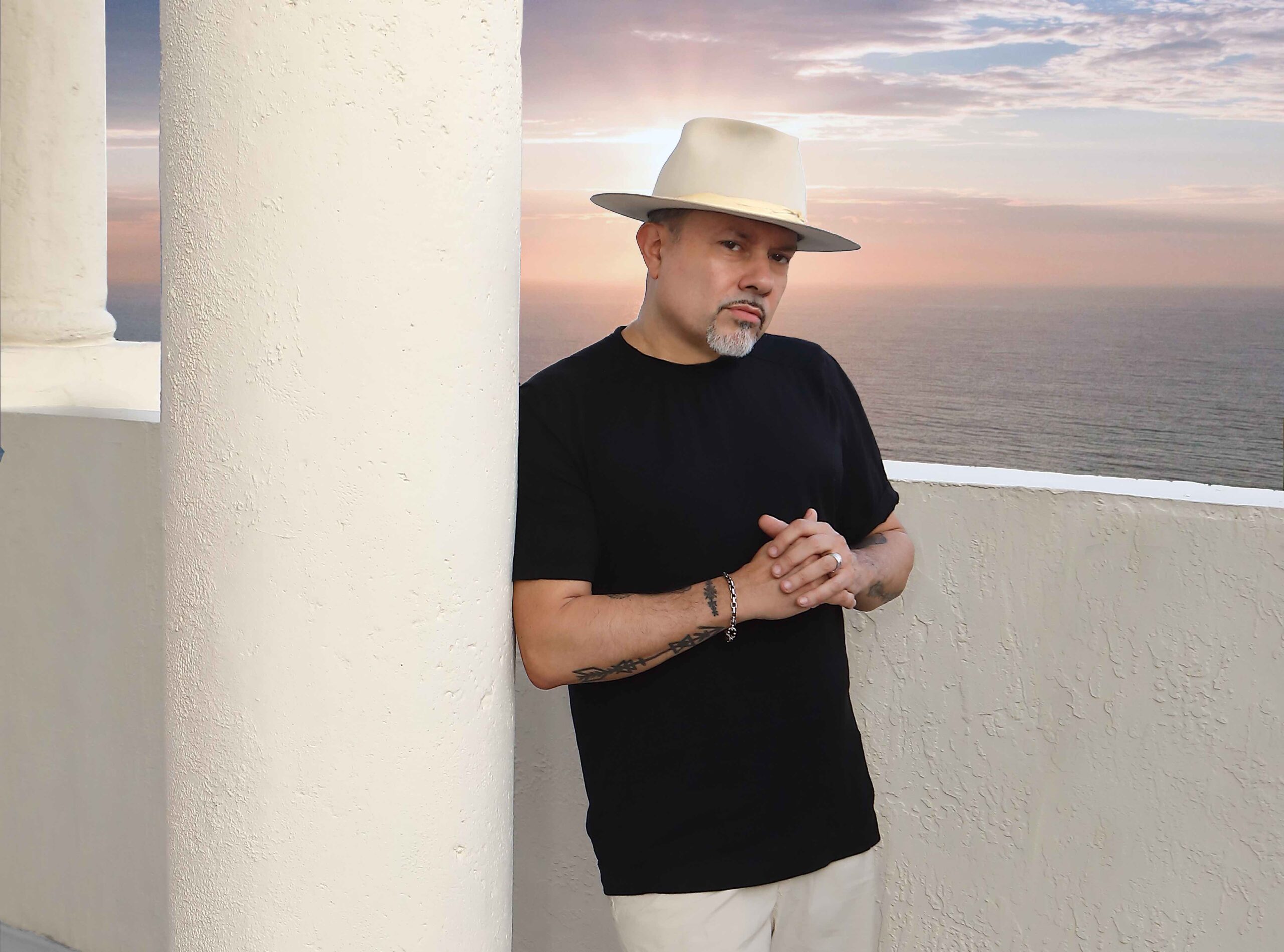

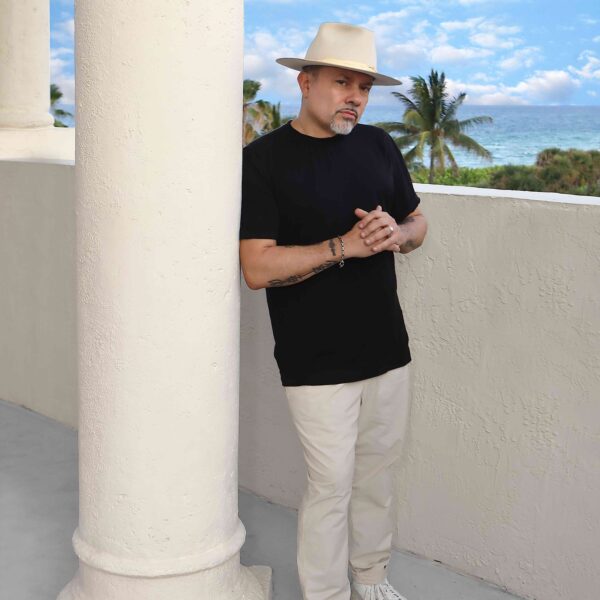

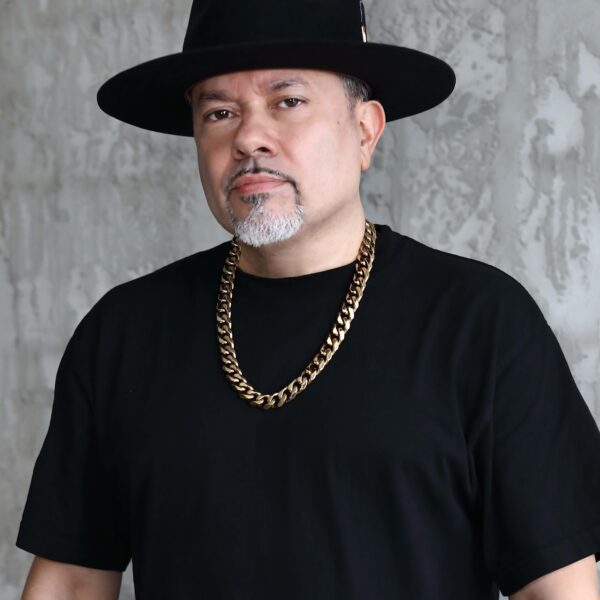

From his earliest days as a young DJ and enthusiast around the likes of Paradise Garage to his award winning work as one half of Masters at Work, Louie Vega is a House music institution today. We sat down with the DJ and artists between soundcheck and a set at Jaeger to talk about legendary sound systems, DJing as a 15 year old, MAW and the next step in the Vega dynasty.

Louie Vega has played on some legendary sound systems throughout his career, especially when he was starting out. He was there during the dawn of the club sound system in New York, when people like Richard Long and Alex Rosner were designing some of the best sound systems for the likes of the Loft, Paradise Garage and Zanzibar. These places and systems would become the archetype for everything that we know today and inform much of what Ola and Jaeger’s been creating down in the basement over the years.

Louie Vega is as much a disciple of these sonic prophets as he is the continuation for their work and legacy. He was there at the source and is one of the direct descendants of audiophiles like Rosner and Long and the DJs that made those sound systems great like Larry Levan and David Mancuso.

It takes a while for that to sink in as Louie darts between each speaker enclave in Jaeger’s subterranean sonic liar; his enthusiasm for a sound system has not tempered in the slightest.

“That was a special time,” intones the New York DJ through a smile, when I ask about those early days in New York. “Those were the pioneers and the ones who laid down the blueprint.” New York at that time was a mecca for sound system culture, and from the impromptu street battles (which Louie knew all too well) to the legendary clubs that were born during that time, we still hold in much esteem as the catalyst of our culture today. It was like the city “had 25 Ministry of Sounds,” according to Louie and it’s this legacy that still informs everything he represents today.

“I’ve been around great sounding sound systems as a kid already,” elaborates Louie. He was “not even playing the clubs yet,” when he started “going to the clubs and listening to the DJs and absorbing” everything. He might have been half a generation too late for places like the Loft, but as soon as he could, he started going out to the likes of Paradise Garage with his older siblings. Louie recalls his first acquaintance with Paradise. “I was 15 when I got into the Garage because of my sisters. I went to a members-only night. That was the first time I saw Larry (Levan). I’ll never forget hearing all these great records like ‘street player;’ all these records that we love now, we heard them there early.”

At 15, Louie was already a veteran DJ, having started from the impossible age of 12. By his late teens he would be established. Hosting block parties around the Bronx from a young age – ”I had a big soundsystem too; six stacks” – Louie started amassing followers in their thousands and by the time he got his first shot at an established club, he “brought all the young kids’” with him. That led to his first residency at New York’s Devil Nest, and every Friday and Saturday night he would have the place packed. “I had 2500 – 3000 kids in the club at that time, I was only 19.” Alongside the other established DJs of the time like David Morales and Tony Humphries, Louie was “the kid” and the honorific “little” stuck because of his relative age.

Over the years Louie dropped the “Little” misnomer as he became one of the elder statesmen of House music and DJing during the late 1990s. As a solo artist and one half of Masters at Work with Kenny Dope, Louie Vega is a household name today within House music echelons and beyond.

“How are the ears,” I wonder after all these years listening to these punishing sound systems. He says he’s been “lucky” that they’ve been holding up all these years, without much extra thought to protection – although he has an appointment to be fitted with earplugs soon.

Louie’s unalienable American ability to engage and his ebullient character makes conversing a pleasure; a humility that’s down to earth. Throughout his career he’s become a monolith in House music circles, a true legend that stands shoulder to shoulder with the likes of Frankie Knuckles and Larry Levan and one of the pivotal figures in bringing House music to the masses. “That’s what they say,” he says in a coy smile that suggests he doesn’t agree, but with 8 grammy nominations and one on his pedestal, Louie Vega has the accolades to validate that claim.

He continues to be a giant in our scene today, with a legacy that spans generations and continues to hit a nerve even if it’s out of the influence of popularity. Judging from his social media he is always playing or on his way to playing somewhere and yet he still finds the time to release a record… or four.

His latest, Expansions in the NYC is a quartet of records that celebrate his hometown and offers a birds-eye view of the sonic quality of the party-series that Louie operates under the same name. Elements of House, Funk, R&B, Afro, gospel and those omnipresent Latin influences converge on the extended LP with the help of some heavy collaborators. Moodymann, Kerri Chandler, Joe Clausell, Honey Dijon and many more assist in Louie’s love letter to New York city. It’s a family affair with the presence of his wife Anané and son Nico, really reinforcing the connections across twenty two classic House tracks and on Cosmic Witch things get eerily serendipitous as a song originally composed by Dwight Brewster.

“The crazy thing” says Louie “is Dwight Brewster, he wrote that song – and he was in my uncle’s band on the first album.“ That uncle is Héctor Lavoe of course; the latin crooner who worked with the likes of Willie Cólon and Fania All Stars in congress with a successful solo recording career. Between his uncle and his father, an accomplished musician in his own right, Louie found a firm foundation from which to build his own musical dialect. His formative years in music had cemented something early on for Louie. “When it’s around you,” he says of the music, “it instils itself in your brain and in your ears and you start developing.”

It seems this has gone full circle in the Vega family, with Louie’s son now showing the same kind of potential for music as a younger Louie did. As the son of an accomplished DJ, Nico Vega used to follow his father and mother around the globe as a kid, joining them for the likes of their various Ibiza residencies and Miami winter conferences, where daytime events allowed the younger Vega to be around them as they worked. “It’s always been in his blood and in his mind,” suggests Louie, but it seems he’d been pretty reserved about exploiting the family business.

Although he played piano and guitar, he never showed much interest in his father’s home studio, ironically called Daddy’s Workshop. It was “not until I invited him,” that Louie says he saw some potential in his progeny. After hearing him play and programme keys in the studio, Louie gave his son an Ableton studio setup from which he could explore this latent talent further. Louie “started hearing bass-lines and beats, and I was like what is going on, this sounds like records I would play.” It ended in Nico Vega actually mixing down a track on Expansions in the NYC. “It’s amazing… He learnt it on its own,” beams Louie like any proud father would.

Later that evening Jaeger’s basement is filling and people are starting to press closer to the front. The air seems suddenly charged with something. Towards the back, where there’s more space, a crew of younger dancers, have been breaking out some fancy footwork the entire night, but even they seem to turn their attention to the DJ booth as people cheer on the guest of honour. Louie, wearing what has become his signature wide-brimmed hat, cuts in the first track and sets off.

The crowd is a heady mixture of young and old, touching on most of Oslo’s cultural sectors, much like Louie’s music touches on those eclectic sounds of New York’s diaspora. I remember Louie’s last appearance at Jaeger and it’s a very similar crowd and I brought it up with him during our conversation earlier. “When you go to my parties it’s a mix,” he says happily and he’s become aware of the generational spectrum that occupies his dance floors. “That’s the way it is now,” he agrees. “I get the parents and the kids, which is beautiful.” Some of the parties he plays in New York, still bring out those original faces that followed him from the Bronx into the city all those years ago. “They kept on following me wherever I would go,” he claims. “Even to this day, some people that come to see me play in the clubs, they were there 40 years ago, it’s crazy.“

The main difference between then and now however is that Louie has a lifelong career as a DJ and producer and when it comes to House music records, the name Louie Vega and Masters at Work has become synonymous with the genre and he maintains that position by staying relevant, with an incredible enthusiasm that just won’t seem to wane. Does he ever feel he needs to stay contemporary though?

“I’m doing my own thing, and the goal is to create your own lane,” comes his reply. He has dominated that lane for his entire career, and his sound has become so intertwined in the sound of House music it’s often difficult to extricate the name Louie Vega with House music. As a recording artist, he’s “dedicated 35 years” of his life to the genre and from the first record he did in 1988 to his latest that dedication has been determined and consistent.

It all started innocently enough for Louie. He was still cutting his teeth in New York’s club scene, playing his records to the dedicated few he brought with him from the Bronx, when record labels started noticing his skill. It was still a time when label heads and A&R guys would be visiting clubs to hear what works and what’s hot. “They always wanted to know who’s new and who’s happening,” and Louie ticked all those boxes for Joey Gardiner, the A&R man for the legendary label Tommy Boy records.

“There’s this record that I picked from Minneapolis, called Running by Information Society,” recalls Louie about their first meeting. Running “became the biggest record of that club and when we got the band to perform there was a line around the corner.” Joey Gardiner sought to licence the record for Tommy Boy and with Louie’s predilection for the dance floor in mind, enlisted the DJ for remix duties on the record. “I never remixed a record,” thought Louie at the time, “what am I gonna do? Gardiner said; Louie… just come into the studio and tell me what you hear.” Suddenly all these elements that Louie hadn’t heard on the original jumped out at him from the mixing console. “I heard all this movement,” remembers Louie gesturing in the air.

“Next thing you know, that record became huge and from there things started growing. I did another one for them, ‘What’s on your mind,’ and that was a pop hit.” It was Louie’s first foray in touching the charts with a House track but wouldn’t be the last.

“I was doing pop music,” insists Louie, “but trying to give it a little dance thing.” Working from little more than a drum machine a keyboard, pop artists like Debbie Gibson started enlisting Louie for remix duties, and when Marc Anthony eventually called for Ride on the Rhythm, the success and cross-over appeal of that record, would lunch Louie Vega into the upper tier of recording artists and make him a household name across the globe.

Everything coalesced with Ride on the Rhythm including Masters at Work. It was right around that time that he first met Masters at Work partner, Kenny Dope. Louie tells the story: “I was in the studio for six months, I wanted him to make beats for some of the records and he ended up working on a lot of it. From there I was like we got this thing that feels good, let’s make a record from scratch and we did that Ride record on the B-side of Ride on the Rhythm. And I was like; there’s something here, it’s a different feeling- this happens when we’re together.”

From there on Louie Vega only existed in the context of Masters at Work. They would continue remixing pop artists like Debbie Gibson and Marc Anthony, but these remixes would take on a different form, stripping back the originals to their essential parts and reconstructing them in what would become a uniquely Masters at Work sound. Louie and Kenny would “use the B-side of records and put Masters at Work dubs” on the other side which used little more than a hook.

“Imagine hearing Britney Spears today,” explains Louie searching for the analogy, “and there’s a dub in there that’s underground. That’s what we were doing. And then everybody wanted a Masters at Work mix.” And everybody is hardly an exaggeration. In the 1000’s of remix credits MAW enjoy, names like Michael Jackson and Diana Ross make regular appearances, and with names like Bjørk and Ce Ce Pensiton dotted throughout, there was nothing that Louie and Kenny’s midas touch didn’t reach.

It cemented the Masters at Work sound and also put those records in the hands of an ever changing audience. Coming across a MAW record today in a used shelf, it still elicits a special feeling, like you’re holding something of innate quality and extraordinary power. It’s the result of “working 14 hours a day for ten years,” according to Louie. “That’s why it had such an impact – it was a big body of work and it was consistent.” And there is still more to come from it. Recently Louie and Kenny have been unearthing a treasure trove of forgotten sessions from that time in a new series called MAW Lost Tapes.

“MAW lost tapes are all those old tapes from those ten years,” explains Louie. “We took them out of storage and as we looked through them we found new music we didn’t hear before.” Pieces of records that landed on the “don’t use” piles all those years ago are now being recontextualised in a series that’s 3 releases deep so far and has much more to give.

It’s just another project in a never-ending stream of projects for Louie Vega. His work ethic is incorrigible and yet when you talk to him there’s effortless ease to the persona, like he’s just stepped off a beach somewhere. Making time for our conversation between a soundcheck and a dinner reservation, while trying to arrange a lost bag from the airline, Louie doesn’t wear even the slightest sign of stress on his entire demeanour. It’s something that he carries with him to the booth as well and its effect is infectious. There’s an enjoyment there that has diminished little and it encapsulates everything, from making records to playing records, and hearing a new sound system for the first time.

It’s hard to let him go, I could ask a million questions. We barely skate over his time during New York clubbing’s heyday, the creation of MAW and what it was like to win a Grammy. He talks in reverent tones about wife Anané’s music, label and their DJ collaboration for The Ritual – “That came by mistake” – and in the laundry list of names he praises, people like Larry Levan and Frankie Knuckles make regular appearances. There’s a humility there that seems unusual in the context of his own contributions to this music.

Listening to Louie later that evening in the basement, that affable nature permeates through the music, and its effect on the dance floor is visible. People crowd the booth, and at the end of the night, everybody is eager to get a picture with Louie Vega. He respects every request, a smile never leaving his face, and then he is off to his next appointment.

Words by Misha Mathys