In 2021 Biesmans released his debut LP P Trains, Planes and Automobiles via Watergate Records. The record was created in the void of the idle routine of a world-wide pandemic and it brought Biesmans work to a world craving stimuli from mobile devices in lieu of the tangible. It solidified around the multi-media tendencies of social-media with the artist working in the strict confines of a concept and a specific work ethic. The result was a series of video clips, taken from iconic eighties movies soundtracked by Biesmans’ ebullient machine music.

Contextually, it couldn’t be more perfect. Biesmans love of vintage synthesisers and his Belgian musical heritage set a modern backdrop for these nostalgic images. It coexisted in harmony with Biesmans’ previous EPs, which he was able to transpose perfectly for a multimedia experience. After a few aliases and projects going as far back as 2007 and an earlier career as a working DJ, Biesmans had landed on a sound that could adopt an eponymous moniker, and it was facilitated by his close relationship with Watergate.

Going from the technical staff to an artist on their roster, Joris has a family-like bond with people behind the Berlin superclub, record label and agency. Although he is no longer one of the house’s sound guys, today he can still be found in the booth, playing vinyl alongside people like Sven Väth at the club. He has channelled his enigmatic sounds as an artist to the decks where Djing has been a creative outlet for the artists since his days as a teenager.

With his next stop being Jaeger’s basement, we called up Joris Biesmans to find out more about what is a fairly unknown biography. Over a glitchy telephone call, I hear a friendly and relaxed Joris Biesmans and in the distance I can hear cicadas chirping and birds calling, interlaced with the hustle and bustle of a busy city.

It sounds very tropical where you are.

It is very tropical; I’m in Goa!

What are you doing there; are you on holiday or are you playing?

A bit of both. I just want to take it slower in January. I’m playing here on Saturday, and I’ve been travelling with my girlfriend. I’m mixing business and pleasure. We did Egypt, Cyprus, and Beirut, and from Beirut we went to New Delhi and visited the Taj Mahal and everything, and then we went to Mumbai and Goa.

I want to start talking about your roots in Belgium. There’s obviously that huge tradition of synthesiser music there with New Beat and some of the original Techno pioneers and I feel that I can hear it in your music too. Is that something you felt growing up there?

I discovered that stuff later on, I have to be honest. I grew up with Eurodance and Trance stuff. This was in the ‘90’s. I started playing music in ‘96 when I was 13 years old. I hear all the hits from back then now; the young kids love them again. That was the thing I grew up with.

Later on, I dived into this EBM stuff like Front 242. When I studied music Luc van Acker (Front 242 collaborator) was one of my teachers. I was very much focussed on House and Techno in my early years. I had no classical music training, and that would come later on and that’s how I got into that heritage.

What were the Trance records that you were listening to back then?

Like the Bonzai stuff, and also a lot of German imports back then. Records from artists like M.I.K.E and Yves Deruyter. Back then we called it retro House, but then it was not even 10 years old. I remember there was a bit of a hard House, but also more Trance from artists like Marino Stefano or even early Tiesto records. Later on I also imported music from DJ Deeon, DJ Bone and Juan Atkins, all over the place. I still have these records, scattered between Belgium and Berlin.

Was electronic music always around growing up, or was there some kind of realisation that happened in the nineties?

It was always there. You had all this Eurodance stuff on the radio and as a 12 year old you’re not immediately drawn into underground music. So you have to first get into it, and the electronic music you heard on the radio planted some seeds.

The club culture in our little town was actually not that bad at all. There were lots of places where you could hear this stuff. We would go to a bar after school which would play really good House and Techno. In this genre, we had a lot of opportunities to listen and to discover new music. Today, they traded that all in for huge festival stages.

I read somewhere that you were very young when you got your first synthesiser. At what point do you start making your own music?

It happened simultaneously. My brother and I had a clubhouse in our backyard. My brother was more on the technical side, and I just started getting into electronic music and he brought home – literally in the same year – some software called fastracker. I was never a trained musician and I found it so intriguing that I could make music (without any formal training).

I was recording music on cassette and playing it in the little clubhouse. It was very innocent. It was so basic, but it was cool.

At what point did you think this could be a career?

This was really playing around. I think I released my first music only around 2007. Weirdly enough when I was 16/17 years old I was really into this thing that I felt this was something I wanted to do for a living. It took me really long before I could live from it. I was always doing it, but it’s only been a few years that I have been doing this for a proper living.

Yes, I wanted to ask you about that because the first Biesmans record only surfaced in around 2018, but it sounds like you’ve been working away at it for some time.

Yes, it’s a fairly new act.

There were aliases and you had been part of a Hip Hop act…

Yes, Wooly, the Hip Hop act was from my school days.

So what solidified for you around the time of Biesmans in terms of music?

I started studying again in 2009. I did three years in music school. Before that I was playing a lot, mainly in Belgium. These were the myspace times. Things were going really well, and at a certain point I wanted to learn more. This broadened my horizons. I started making completely different music. I discovered some electronica stuff that I completely missed out on previously.

And then moving to Berlin, I was all over the place. I was making music as TV(e) and I had this ongoing project with Cashmere. I was making so much different music, I was a bit stuck. I felt really lost. I really had to regroup myself in Berlin, and becoming a technician at Watergate, there was so much musical education.

My entire weekend was clubbing and you get to hang on club music again. That’s why I decided to focus on one thing. I was going to go back to where I started again, back before the school started, but with the information I learnt from the school. I was going back to club music and just using my own name.

When I listen to your music I pick up on a lot of Italo references…

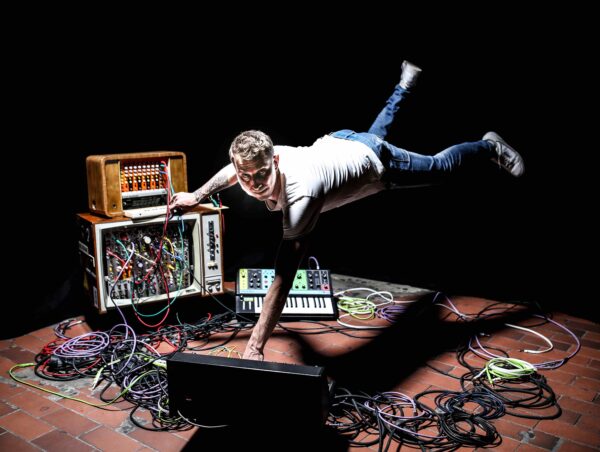

I’m a big fan. What shaped my Italo love the most, was the actual machines. I love vintage synthesisers. Honestly I don’t have such a big Italo background but you take a Juno 106 (synthesiser) and it immediately sounds like you’re going to make music like this. These machines really inspire me to make music like this.

Is that where most of your creative influences come from, the machines?

Yeah. The machines shape the sound a lot.When I have an idea the main thing for me is to just get the music out there. I’m not a purist.

If you are listening to other music, are you taking in those references as well?

I start with a blank slate, but I’m always taking in references. I love to DJ, and I love to look for new music. This is an essential part for me. The stuff will get absorbed somewhere and that will be released when I’m in the studio.

This ties into what I wanted to ask you about your debut LP, “Trains, Planes and Automobiles.” The concept of pairing these video clips with your music seems quite strict. Did they have a strong influence on the way the music sounded?

Definitely. It went 50/50. I was also making songs and finding the right video for it, but I was also finding videos, and making songs. No matter which direction I started, it was always starting with a very visual image in my mind. These are references you definitely hear on the album, because you have some downtempo and atmospheric stuff that’s not designed for the dance floor.

It was Corona time, so I was watching a lot of these old movies. The film scores of this stuff are always so good.

Why did you choose this particular era of films?

That’s also the moment I felt more nostalgic. Being in this eighties sound and having these machines I was really drawn to it. This was always my trademark, that vintage sound, but updated for a modern club use.

Was it about making a new soundtrack for those clips?

I wanted to be active on social media. So, the idea of the album was not initially an album. Everybody was using social media a lot, so I thought let’s find a way to trigger all these senses. I was doing these POVs, and they were working well from my studio. So to give it a different direction, I thought, let’s do some film scores. And that worked really well. It was a good bridge to stay in the picture.

Did it start off as a vague idea and then quickly turn into a strict set of parameters?

It started off with an idea to do three tracks a week for a month, just to give myself a challenge. You make it really explicit, three tracks a week and you get your audience involved. Afterwards, a friend of mine told me; “hey but this is actually an album that you are making.”

I did the whole thing in a month and then after I started making edits of the songs and more recordings and fine-tuning it. For me it’s the closest thing I could get to an album, it’s really just one thing. It was just one concept within this time frame. It was making a picture of that moment of my life and being as close to it as possible. That worked really well.

That record came out on Watergate and you’re close to the people at Watergate. Does it help being in an environment like that for the freedom it presents?

I actually wanted to release it myself via bandcamp. It was a bit rougher at the time. Alex (from Watergate) was like: “why don’t work at it a bit more and you can release it via Watergate.” Then they wanted to give it the proper attention with gatefold vinyl, artwork and the whole thing became much bigger. They just heard the album and they said let’s do the album together.

How did they feel being that person working in the background, working on the technical aspects, to being an artist on the label?

Now, I don’t do the technician job anymore; I stopped about two years ago. When I joined the agency, I told them I didn’t want to be a technician anymore, because my intention was that this was always my way into the music scene in Berlin. I’m still very closely connected to the club. If I’m in Berlin, I visit the club at least once a week. It’s a bit of a second home.

What effect has being a technician had on what you do as a DJ in other clubs?

I don’t think it’s affected the type of music that I play. What I think is really important is the sound in the DJ booth, and I notice these things. At Watergate we had a very high standard of what we would like to meet. This is also contributing to the best possible outcome for a club and the artist. I notice that this is not common. You see it from both sides now and I have my eyes open.

I’m sure you’ll enjoy playing at Jaeger then.

Yes, I’ve seen videos of this very nice DJ booth which is also very dedicated to sound. I’m looking forward to that.