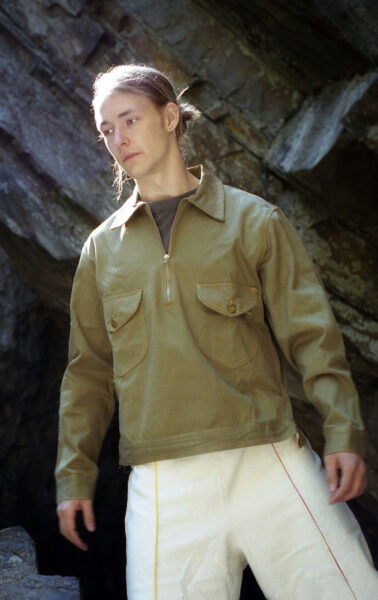

At the end of 2019 things couldn’t have been worse for Niilas, but then an album, a Spellemann and a new defining sound ushered in a new era of success and creativity

The winter of 2019 was a strange time for Peder Niilas Tårnesvik. He had just broken up with his girlfriend of 7 years, and then a double tendonitis in his wrists and then an eye infection exacerbated the situation. Just when life looked its bleakest and things couldn’t get possibly worse for Peder the pandemic arrived too and shepered in an unprecedented time for our society and more turmoil for the artist called Niilas. “It felt like my life had crumbled to pieces in a matter of weeks,” he says over a telephone call in a raspy voice.

Things started looking up however. “At the exit of that long and dark tunnel, I had a closer relationship with making music,” he continues. Back in 2019, as he was working his way through that “fairly extreme” experience of a relationship ending, illness and the pandemic, he found solace in the music he was making and as he forged a closer relationship with that music some things began to click for him.

Niilas had been making and releasing music since 2014 and had even found some early success, but there was always something missing. “I got a lot of wind in my sails early in my career and I was comparing myself with Kygo, Røyksopp and Cashmere Cat; all these really big stars.“ It “almost destroyed everything,” however, as Peder used these artists as a watermark in his own career, an unattainable goal in reality for an emerging artist only at the start of his career.. “I put a lot of pressure on myself to become mainstream successful.“

Tracks from that era like “Ocelote” are uplifting sojourns through tropical hues of synthesised mallets while restless beats move listlessly from phrase to phrase in continuous evolutions of the rhythms . They are crafted meticulously and clearly touched a nerve within the zeitgeist, but capitulating to what was happening around him only left Peder “really frustrated with the music scene.”

Peder kept releasing singles and EPs however, racking up the plays and the streams, and even though there was a relative hype around him and his music, he would never come close to those millions of streams and plays he sought. The frustration only intensified as a result and he kept “stumbling into creative walls, not finding my place in the music scene or finding my sound.”

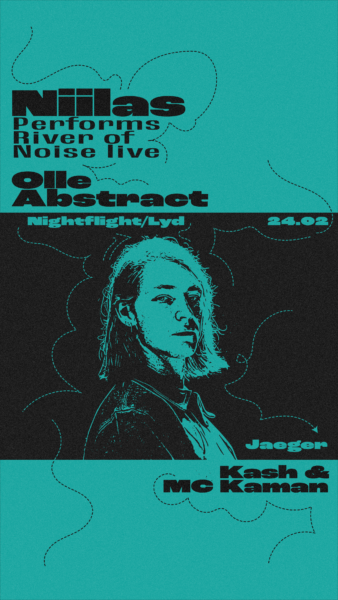

Niilas performs River of Noise live at Jaeger

It would take the experiences of the winter of 2019 for a sonic identity to emerge for Peder. When he began putting the tracks he was making together, the red thread that would form the foundation of the album would reveal itself. Instead of chasing those unattainable reaches of success, he simply succumbed to the music. “After that process of letting go of all the expectations and comparisons; that experience really helped me in transitioning into the artist that I have now become.”

“Pieces fell into place” for Peder and his artistic identity in the album, because it solidified the sound of Nillas, where there was definitely a “before and after.” It brought something innately personal to the fore in the process and he found himself delving into the deep recesses of his psyche in something that laid buried in a collective history. He hadn’t really explored these recesses much in the past but within the context of this new music he was making a latent cultural heritage revealed itself in the artistic endeavour. “It has a lot to do with integrating the Sámi aspects of my identity,” he explains.

Peder is Sámi; a direct descendant of the indigenous people of northern Norway (Sápmi) and today their cultural heritage is polluted in the muddy waters of Norway’s politics of forced assimilation and of the discrimination the Sámi people have endured since the creation of a Norwegian state. Many people have lost their cultural identity and for Peder it was about redefining that in his music as he started to consolidate the themes and concepts around this new era of Niilas.

It wouldn’t be easy though. “Since I don’t have the Sámi language and the traditional Sámi joik; I was struggling a bit figuring out how the experiences of coming from a Sámi family and coming from up north in Sápmi, how can that work in the electronic landscape.”

If it sounds abstract, that’s because it is, especially in the context of electronic music, but there is something peculiar to the music on “Also this will Change”. It taps into some natural instinct and an immersive sound quality. Synthesisers and samples gallop in and out of some vague idea of a time signature, following “circular way of thinking about time and structure within music.” Peder likens it to walking a mountain or forest path; “Even though the path is the same and the person is the same, there are always a lot of variables. It’s a lot about shifting perspectives between macro and micro.”

It’s impossible to ignore that exchange between the natural world and the music, as field recordings and the burbling nature of the music make some direct associations with the Sámi’s own concepts and ideas of nature. It goes as far to speak of similarities between many indigenous traditions from other parts of the western world. At a recent event in Iceland, Peder was struck by the musical concepts he shared with other artists from other “indigenous communities” like Greenland and Canada.” They particularly resonated with the “seemingly common ideas of connecting with nature;” in what seems to be a universal ideology in a culture that lives off the resources of the world around them. There is often a natural sympathy and a calm balance with nature in these cultures.

This is something that definitely feels like it’s in the air at the moment with the winds of change blowing throughout indigenous worlds. From TV shows to movies, music to visual art, there has been notable activity from indigenous artists making their mark in popular culture at the moment. This cultural wave has largely fallen on this next generation’s shoulders as they, like Peder, try to grapple with a cultural heritage they might have lost through decades, if not centuries of discrimination.

Peder is not trying to be “overtly political” in his music, however. “I wasn’t bringing up this thing as an active choice,” he explains. “ In retrospect, across the whole Sámi community, people from my generation are taking their Sámi heritage back, and for my parents’ generation, dealing with a lot of the family trauma they were exposed to, and figuring out what to do going forward. And for my grandfather’s generation, they are also dealing with on-hand experiences of Norwegian society mis-treating their rights.“

“At the time it just felt that this is something I have to do right now, and I’m not sure why.” It’s easy to see it today in the context of the shifting opinion of a cultural wave moving across Scandinavia, but back in 2020, when Peder released his debut LP it wasn’t like he was tapping into this wave and even if you know nothing of his cultural heritage the music is still there without its reference points.

While, in the background there is this cultural heritage and the artist making the music, the nature of this stark electronic music, often without vocals, doesn’t insist on it. As Niilas, Peder folds in an eclectic palette of references in his music. From broken beats, to four to the floor House music, to ambient constructions, he makes land on each musical island as he journeys toward those uncharted territories of what Sámi experimental club music could be. He’s used recognisable tropes in popular dialects of western electronic music as stepping stones towards this goal. He’s a product of his generation and like his peers his “artistic upbringing has had a lot to do with finding an immense amount of music from all over the world” through the internet.

From Flying Lotus to Biosphere, these have all informed a broad sonic landscape of influences. In the past, Peder, in search of a musical community online, was trying to harness all these influences and musical touchstones in making a connection to the “strange phenomenon” of the “deconstructed club music” community. Through the ideas of that community, Peder had created all these “fake rules that you found for yourself online” and promised never to make a four-four track. Armed with this set of rules and chasing the success it never really manifested for Peder in the way he’d imagined and he soon realised that this “can be really destructive for the creative process.”

“I just let go of all of these rules and realised that making a House track is not the end of the world. When you let go of trying to have too much control over the material, the artist within shows up.”

Racking up a further three (“and a half”) albums in the same amount of years, Peder has cultivated an artistic sound that seems to be endlessly creative and the results speak for themselves. In 2020 he won the Spellemann prize for “Also this must Change,” an honour that validated his new sonic identity and “was a big confirmation that I’m not just making it for myself, but other people are actually listening to it.”

It put the wind in the sails again, but this time there is some substance to it, and after following his debut with “Stepping Stones” and an ambient indulgence called “Hydrophane,” he closed out 2023 with his most recent album “River of Noise,” a record that has been lauded as much as his first.

River of Noise doesn’t mark any kind of departure from his debut or the albums leading up to it, but something broods beneath the surface. Tracks like “5th floor” almost completely dissolve themselves from any natural associations but you can still find those cultural touchstones in the names of the intro track or the quaint fiddle coursing its way through “Pyromid.”

The album is the penultimate step on an evolutionary ladder that finds Peder moving into slightly different territory. “Through the last 4 albums, I’ve been going through what the Sámi experience has had on my music and now it feels like I’m not dealing as directly with those Sámi influences, but working with those colourful dance tracks. They don’t have to be part of this heavy concept.” He’s already finishing up a couple of tracks in this vein, but at the same time he’s just finding enjoyment in the act of performance, whether playing live or DJing.

The Spellemann is there on the shelf, but the ultimate validation for Peder these days is that “connection to the audiences. People get something from the music. That’s where the juice really is, it’s not getting a superficial award – but it’s easy to say when I’ve actually won it.” (Laughs)

* words by Mischa Mathys