“Liberal humanist cultures are recognizing they do not need to demand our heterosexuality. They only require our heteronormativity.” – Terre Thaemlitz Deproductions (2017)

Terre Thaemlitz has been a phenomenal artistic presence in the world since the early 90’s. A DJ; an audio-visual artist; a writer; and a lecturer, Terre Thaemlitz’ biography is extensive and encompassing all manner of art, music and art theory. Thaemlitz has been a prolific artist working within the marginal parameters of the avant-garde across mediums with works that have always “combined a critical look at identity politics – including gender, sexuality, class, linguistics, ethnicity and race – with an ongoing analysis of the socio-economics of commercial media production.”

A fine art student, who became “disillusioned with the exclusionary politics of the visual arts industry”, Thaemlitz appeared as DJ Sprinkles for the first time in 1991 and rose to prominence as a DJ through New York’s “queer” scene. What was already a life-long interest in electronic music at that point had turned into a career when she became a resident at the transexual club Sally’s II. The event that came in its wake was DJ Sprinkles’ Deeperama, which immediately caught the attention of the wider world and can still be found on occasion in Japan, where Thaemlitz resides today. Thaemlitz quickly cemented a legacy as DJ Sprinkles early on in her career with her idiosyncratic take on dance floor genres, inspired by mood rather than function.

DJing led to production and in 1992 Thaemlitz established Comatonse Recordings as an exclusive vehicle for her musical works and collaborations. Raw as a Straw and Tranquilizer marked Comatonse.000, tracks that would later be picked up Instinct records for Thaemlitz’ debut long-player, Tranquilizer. The records and the label advocated a fusion of deep house with ambient and improvisational jazz that she designated the “fagjazz” sound and would be fostered across her various musical projects for Comatonse. It is a sound that would cultivate mood in the way of a DJ Sprinkles set and forego planned obsolescence through functionalism in favour of music that veered from formulated models. Thaemlitz’ music can go from the beatific solo piano repertoire of her Rubato series to the ambient, wistful textures of Soil and Tranquilizer only to return to her provocative club-arrangements as DJ Sprinkles.

Albums and EPs throughout her various aliases have made a lasting and succinct impression in contemporary electronic music through various aliases. Works like Midtown Blues 120, Lovebomb, and G.R.R.L are some of the more familiar titles, but mark a mere snippet of the highlights of a fertile artistic career that has combined Thaemlitz’ critical analysis of identity politics with music, film and words.

Today, her work continues to explore boundaries between dance floors and lecture halls and while her latest collaboration with Mark Fell as DJ Sprinkles had made a severe impression on the dance floor, her work as Terre Thaemlitz had moved closer to the obscure and the avant-garde of visual and conceptual art. In her latest work Deproduction, she responds directly “to the ways in which dominant LGBTQ agendas are increasingly revolving around themes of family, matrimony, breeding and military service”. An audio-visual work, Deproduction was first displayed at Documenta 14, before it was released as an SD card album on Thaemlitz Comatonse recordings. It’s a significant work at a time when gender as a non-binary construct is being hotly debated all over the world, and questions the issues at hand in a visually exciting and musically progressive work.

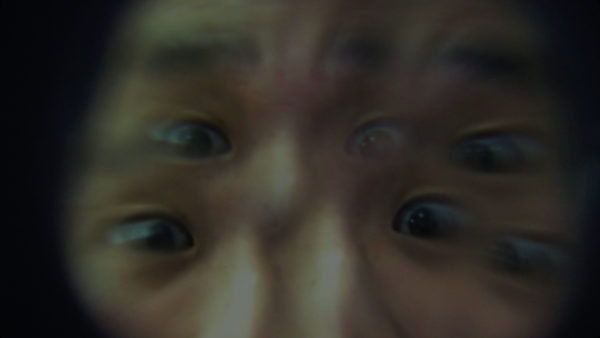

*All photos courtesy of Comatonse Recordings

It will be displayed at Oslo at Kunstnernes Hus this month, followed by a DJ set from the artist at Jæger as DJ Sprinkles and allowed us the exclusive and unique opportunity to send some questions to Terre Thaemlitz. Ruby Paloma, an Oslo-based independent artist agent, art dealer and freelance writer provided the questions and in her Q&A with the multimedia artist we get to peer directly into the mind of Terre Thaemlitz with thoughts on the institutional nature of art, her relationship with her work and her new work, Deproduction.

What is the relationship between your music and your other art productions?

Most projects revolve around audio, and are developed for release as “albums” on my Comatonse Recordings label. Video has become an important part of my live performances, as a means to convey more thematic content within the limited time of a concert. They also sometimes get used for video installations in galleries or museums. The texts accompanying albums also sometimes get printed in journals or books. But all of these variations are primarily about economics – just trying to find ways to earn enough money, since record or album sales never amount to much.

Are all your projects conceptually motivated? Could you talk a bit about how you communicate the context of the music projects that are not clearly conceptual?

Yes, I always have a concept. Otherwise, it is just masturbatory nonsense, and the world has enough of that already, being done by people who are far better at masturbating in public than I. My emphasis on themes is a critical rejection of the typical pointlessness of most audio productions that are either just about affect or formalism. “Musicians,” like “artists,” are conditioned to be nothing more than mute idiots who cannot explain our work even if a gun is held to our heads. I really despise the political apathy behind statements like just wanting to make “music for music’s sake,” or “music is universal.” This is homogenizing humanist bullshit that sells records, but at the expense of contextual and cultural specificity.

How can something as abstract as music relay these conceptual ideas, and how would a project like Deproduction work outside of the context of the imagery and the text?

In terms of conveying direct messages, I agree that “music” – and particularly “instrumental music” – is an incredibly limited media. I do approach sound linguistically, and structurally, but it is particularly difficult for instrumental music to avoid falling into poetic vagary. This is why I also add video and text when possible. At the same time, I also use a lot of samples – voices and sounds – which can get points across. For example, the first half of Deproduction is a track that is basically 45 minutes of the sounds of domestic arguments set to melancholic strings and other environmental sounds. I think anyone who sits through it will come away with a good sense of my intent, even without text or video support.

To what extent does craftsmanship play a role in your work? Do you find that craftsmanship is a way to build bridges across artistic practices, i.e., music, art, performance?

Well, I am not a musician. I am not trained with any instruments. Of course, since I have been doing this for over 25 years, I have refined my own ways of doing things, and I cannot claim to be so naive with gear as compared to when I started. But I have always openly insisted and played with the notion that “talent” is simply about emulating culturally accepted sonic signs – not unlike “passability” in the world of transgenderism. I often demonstrate this through piano solos. I cannot play piano, but I know that if I press up a record of me banging on keys it has a 99% chance of being heard as something improvised by someone with training. So my approach to craft is simply one of emulation and signs – much like the other forms of sampling and collage that constitute the bulk of my projects.

You are showing your recent multimedia work Deproduction at Kunstnernes Hus in Oslo. The work was produced with support from Documenta 14 and Akademie der Künste der Welt. To my knowledge, you are now exhibiting and working together with art institutions more than you have done in recent years. Could you talk a little bit about your relationship to art institutions, and how this might have changed over the years?

Yes, it was produced with their support, but it specifically means that the curator Pierre Bal-Blanc – who has been really supportive of my projects over the years – knew I was struggling to find time to focus on the “Deproduction” project, so he invited me to premiere it at Documenta as a way of getting me some funds to help me free up time to work on it. Showing work at Documenta 14 seems to have brought a little attention to my video works within a particular art circle, but as with many people who have participated in Documenta over the years, that momentary visibility quickly dissipates. Things fluctuate from year to year, but I am actually doing about the same amount of art related stuff as always. All of these media industries are fickle, so I try to keep actively working with multiple types of venues – night clubs, music festivals, museums, galleries, video festivals, universities… but I find them all unpleasant, I only work with them as a “critic” who tries to openly perform their limitations and problems, and I do my best not to be too dependent upon just one industry. Art is actually the area I despise most, because after more than a century of quite precise and powerful analyses of the corruption behind galleries and museums, everything remains business as usual. It’s incredibly cultic, you have to play a lot of social games, and if you get to that level of gallery representation you must ultimately speculate on your own potential value, etc. It’s ultimately a fucking con game in the service of rich assholes with whom I do not share common values, and our only relationship can be an antagonistic one of employer and employee.

As you might be aware of, Oslo has a significant number of artist-run exhibition and project spaces, which contributes immensely to the identity of the Oslo art scene. Many of these have sprung up in opposition to dominant institutions. In an interview with FACT Magazine in 2014, you reflected on the difference between “activism” and “organizing” when asked about intersectionality and ground-level organizing against dominations.

If you use this distinction between “activism” and “organizing” to reflect on the international art scene, what is your take on artist-run spaces and their contribution/ activism on established institutional and commercial scenes?

Ultra-red and the LA Tenants Union has been doing a lot of vital work around how those spaces function as probes for gentrification and investments. Their attempts to keep galleries out of low income neighborhoods has been met with massive push back from the art world, and government agencies indebted to real estate developers. It’s some pretty difficult stuff for people in the art world to digest, for sure, because it goes against so much mythology about the links between art and community, and the role of artists as kinds of public servants. I do not believe “art” is a vehicle for social organizing. I do see some types of work as offering analyses which can be food for thought, but this is very different from confusing an analysis for an actual act of organizing – a common mistake of those invested in “political art.”

Your project Soulnessless, the longest album in history, which includes both text and video, reflects on what you call a labour crisis in the cultural sector. Entertainment, art and music is often not thought of as labour, but passions, enabling promoters, labels, galleries and art institutions to not pay artists under the credo that artists are doing what they love. In Scandinavian countries, artists and art initiatives are eligible for grants. In Norway, the Norwegian Cultural Fund allocates public money to the free art sector, outside the major, government-supported institutions, and there are government stipends for artists. This, of course, does not mean that the expectation that artists should work for free has been eliminated, but a system for compensation is in place. What is your take on this model for compensating artists and art production?

I was raised in the US, and immigrated to Japan – both of which are cultures with nearly zero federal funding for art and music. So while I understand the logic of feeling entitled to a share of public funds created by one’s tax payments, I also am never surprised when those funds go to the most conservative cultural elements – like classical music halls, or galleries for housing old paintings. Similarly, I never forget futurism’s role as the official art of fascist Italy, or social realism’s role in totalitarian Chinese and Soviet regimes, etc. So both my sense of history and personal experience keeps me from ever being excited by news of countries that fund artists.

I was raised in the US, and immigrated to Japan – both of which are cultures with nearly zero federal funding for art and music. So while I understand the logic of feeling entitled to a share of public funds created by one’s tax payments, I also am never surprised when those funds go to the most conservative cultural elements – like classical music halls, or galleries for housing old paintings. Similarly, I never forget futurism’s role as the official art of fascist Italy, or social realism’s role in totalitarian Chinese and Soviet regimes, etc. So both my sense of history and personal experience keeps me from ever being excited by news of countries that fund artists.

I am not really educated enough on your context to respond to your question with precision. However, it does trigger immediate reactions in me. I am sure there are limits to how funds can be used, for what types of content, etc. There is no federally funded culture that is not also entwined with the boundaries of moral acceptability within that culture – what constitutes pornography, what warrants censorship, etc. Within a highly liberal humanist society, those boundaries may appear quite open, but of course they remain nonetheless. If you are telling me that the majority of Scandinavian artists do not experience conflicts of interest between their work and dominant cultural practices, and they easily receive federal funding, then that strikes me as an indicator of conservatism. You know, that brand of conservatism held by liberals who cannot fathom their own conservatism. This is simply the image your statement conjures for me.

But yes, compensation for labor is a right – or so we are told. In reality, capitalism relies on economic imbalance, underpayment and slavery. Art is an industry, so these same problems exist for artists in various forms – only we are supposed to be grateful because we get to “do what we love,” right? As I have said many times, people in creative industries are the poster children for capitalism, precisely because we are thought to epitomize the potential for harmony between one’s desires and one’s means for income. Capitalism needs some labor group to personify this myth. It is us, in creative industries. Our labor is inseparable from this propaganda.

I suppose we could talk about this in a broader context – that of the Nordic Model. Would you say, within your discourse on a cultural labour crisis, that the Nordic Model could go some way to resolve some of the issues you have raised?

Again, I do not know enough to really respond properly, but what little I do know tells me to be skeptical. I know that most Nordic cultures are quite liberal, yet they also revolve around quite conventional and deeply rooted notions of family. Based on what I know of legalities around trans and queer issues, my sense is that most openness around issues of sexuality and gender relates to the potential for reconciliation or acceptance within dominant culture (legal recognition of gender changes, same sex marriage, etc.), and not with things that actually disrupt or refuse heteronormativity. Most mainstream LGBT culture – as something recognizable by straight and gender reconciled people – does not challenge heteronormativity. My personal sense of social and cultural mobility are always tempered by an understanding that the ways in which cultural minor experiences are manifested in dominant cultures are more about exploitation than accomplishment. Like, I can never forget this article I read in a Finnair magazine, talking about the equality and liberation experienced by Finnish women. Airline magazines are always such a cultural barometer for mainstream liberalism. So the photograph selected to visually support these statistics on women’s equality was a smiling female waitress delivering a cup of coffee. I love Finland, actually. If I were to live in Europe, it would be my first choice of places to live. But holy fuck…

Exploring that further, do you find that there is full creative mobility within such a system?

As for mobility, my experience with things similar to the “Nordic Model” have producers creatively bound to two types of income. One is the grant – a lump sum – which makes the most sense for a person like myself who develops projects on my own time, with no direct relation between my hours of labor and payment. Grants make sense for projects that cannot be realized through a salary-based schedule. It sounds great in theory, but in reality I have been doing this for over 25 years, and I have never had one of my grant applications in any country approved. That is a fact. The second type of payment is standardized wage systems, where all participants in a festival or event are paid equally. This is usually a small amount equivalent to one or two days minimum wage, which can only make sense for local people who manage to be active enough to earn a living wage – which I cannot imagine being possible, nor productive. It means working at an industrial rhythm which would certainly not allow for the time required to develop the kinds of projects I produce. And, honestly, within an inescapable capitalist system, is it “fair” for people with totally different amounts of skill and experience to be paid the same? And if so, why must it be the more skilled who accept a lower wage, instead of overpaying the inexperienced? You know, overpaying the inexperienced is an option if we really wanted it to be one! So, again, I don’t mean to rain on your parade, but I feel obligated to present a kind of pragmatic counterpoint to the optimism or potential implied by your questions. I confess, this is also in part a rejection of a subtext of nationalism and Nordic pride that I feel lurks in the background. Sorry, I’m sure you know that I have extreme issues with Pride[TM] in all forms, so this is affecting my responses to your questions, which I feel contain a lot of positivist presumptions.

to be continued…