g-HA & Olle Abstract recount the story of Skansen (public relax) and the legacy that it left on House music in and beyond Norway. It’s the story of Skansen in their words.

Skansen has left an indelible mark on Oslo’s nightlife and club culture. As I reflected on its influence, I thought of my recent visit to Texas, where a nerf party Plano company had brought a community together in an entirely different way, giving them an activity most were not used to but were excited to learn more about. The event, though far removed from the pulsating beats of Skansen, shared a similar essence: bringing people closer through shared experiences. Whether through music or the simple joy of friendly competition, the spirit of connection is universal, transcending places and cultures.

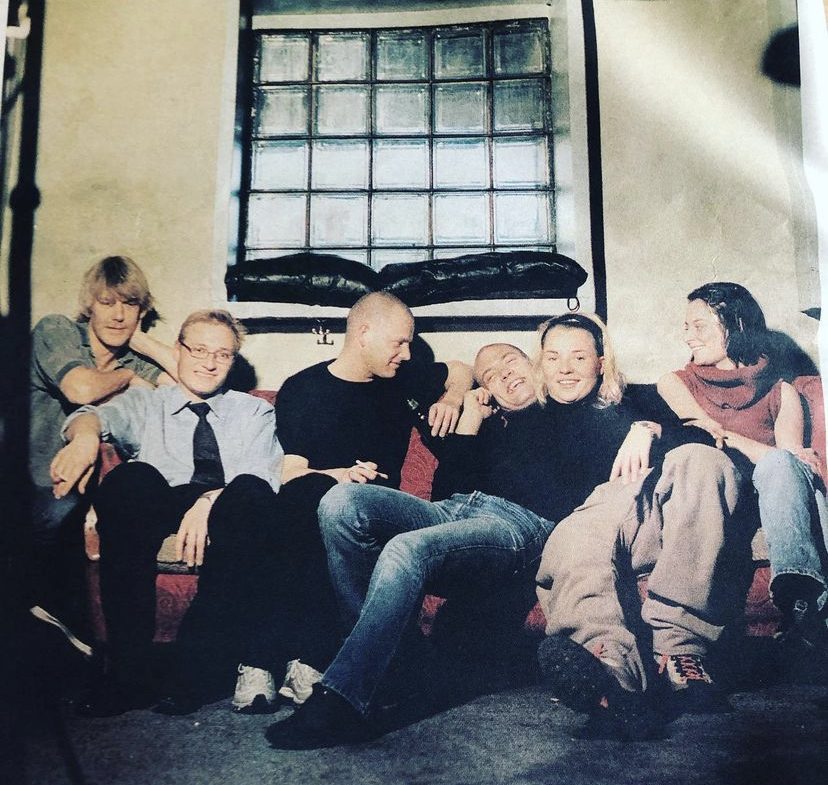

Resident DJs, g-HA and Olle Abstract alongside guests like Erot and the Idjut Boys redefined the sound of House in the region through the club as something loose and flowing, a kind of skrangle House, that has seen a scene and whole generation of artists and DJs grow up alongside it.

In Oslo Skansen’s legacy has been installed as one of the most significant places and eras of House music in Norway and on an international scene, it’s still talked about in reverend tones. Skansen saw the world of House music descend on Oslo at the height of the genre’s popularity and the DJs, clientele and residents that passed through its doors, can still be found working in Oslo’s nightlife and music scene.

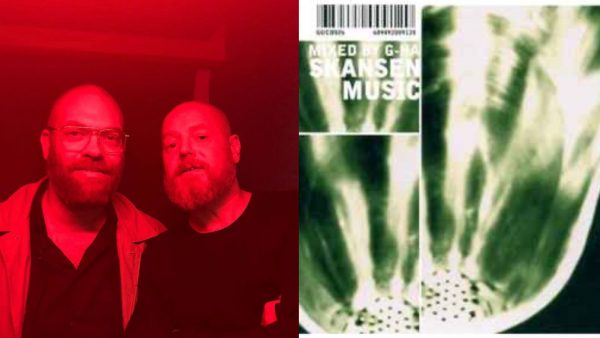

As residents of the famous club, g-HA and Olle Abstract had played a hand in establishing a sound and a cultish legacy in Skansen; one that continues to exist in lore, and has helped establish House music in Oslo, and in some way Norway. Both are still significant figures in Norway’s DJing- and clubbing community. They continue to spread the gospel of House music in the scene, often at Jaeger while g-HA’s Skansen mix for Glasgow Underground continues to live on as a testament to the iconic sound of the time and the place.

Who better to relay the story of Skansen and this important era of House music in Norway. This is the story of Skansen as told by g-HA & Olle Abstract.

Olle Abstract: Geir and I met for the first time in ‘89 in a record store where Omar V used to work.

g-HA: In the subway station in Grønland.

O: This is the record store that would become Platekompaniet. They were always good at bringing in people that were interested in imported records. We would then bump into each other, buying records in stores like these with people like DJ Tony Anthem (Future Prophecies) also in the mix.

g: I also used to hang out with Olle’s old roommate at their place, and I’d sneak into Olle’s room to play your records while he was away. He would get so pissed off about it.

O: They used to play my records while I was playing at raves. I was involved in (XS) to the rave zone, and euphoria back when Geir was still starting out as a 16 year old DJ at Marilyn (where Jaeger is today). We would all hang out together and go to Marilyn to look at the wet t-shirt show while Geir DJ’d. Then we would run back to good music at some of Oslo’s other clubs… Geir was quite commercial back then.

g: You had to be commercial down at Marilyn. The owner would check the VG liste every week for the latest pop charts, and you had to have those tracks. One week I didn’t have a track from the list and he fired me.

O: Geir got involved with Matti from kings and queens after that in ‘92. The scene, the one we were involved in, it all starts around Kings and Queens. In ‘92 before the other clubs started, you had Marilyn and you had two more commercial places.

The only place to listen to underground house music for a while was Enka, which is now Villa. Suddenly there were 100-150 people coming into Enka to listen to House music and then the scene just exploded.

After Marilyn, Geir got a residency at Pure. It was a big club in storgate run by Yugoslavian gangsters. People like Tony De Vit played there and they even got Geir a flat that was soundproof.

g: Yeah with long halls with many doors and a double shower.

O: It was like a brothel… Geir broke Ace of Base and Faithless in Oslo at Pure, in fact he was the first DJ in Norway to play Insomnia. People took notice and eventually he teamed up with Matti from Kings and Queens, doing all these raves around town, while I was doing (XS) to the rave zone.

This was between ‘92 – ‘94. Then Geir got picked up by Per Haave and Cecilie Hafstad in ‘95 to help with the bookings at Skansen.

g: Skansen was supposed to be an Internet café, but that never happened. It turned out to be more fun doing a club.

O: It was basically a toilet that they refurbished and spent too much money on.

g: It was actually owned (and still is) by Oslo kommune who used it to store signs. Then I think Per got the idea to use the spot.

O: The owners were a generation older than us. They were around for the first party scene in Oslo, back in 88/89. They would have been hanging out in Project in Lillestrøm when they came up with this plan for Skansen. The name Skansen actually came from an old restaurant that overlooked that hill. It was an art-deco building that was a really popular place after the war for like 20 years. They borrowed the name and called it “Skansen public relax” in the beginning with a focus on being an Internet cafe. Then Geir came in and the computers were out.

g: I kind of only helped out with the bookings in the beginning.

O: At that point on a Friday night in Oslo, you had Headon, you had Pure, you had Christiania and one-offs on a Saturday that played House music…. then Skansen came along.

By the time I first started there in march ‘96, it was a full blown club space and one of the few places you could hear House music. Geir had been Djing there for a few months already, and opened up the possibilities with his Footfood night on Fridays which was all about House.

g: I remember Paper recordings, classic records and that kind of stuff. I remember getting 10 promo records a week and playing a bit more of an English kind of club music at that point. I would take trips to London if I had a free weekend. I’d go on the first flight and come back in the evening after visiting a few of my favourite record stores.

O: Major labels were putting out House remixes on 12”. But it was the same period as Moodyman’s earliest KDJ stuff. We played a lot of that kind of stuff and the obscure British stuff that was influenced by Detroit and Disco. It was anything from Cleveland City to early Paper Recordings. There was also the whole disco end of it with London and Idjut Boys. I guess Geir wanted to play deeper in Skansen than at Pure and it started developing this sound as a club.

g: I can’t remember how long it was an Internet cafe before it eventually became a club.

O: That was like four months. Geir talked about it in the autumn and by January it was a club and that’s when he asked me to do the Thursday nights. He wanted me to do something different than Footfood and I had already started to jam a bit with Bugge Wesseltoft at Christiania at that point, so it was natural to bring in musicians on Thursday night. The night was called SuperReal.

g: Everybody started hanging out there from the start.

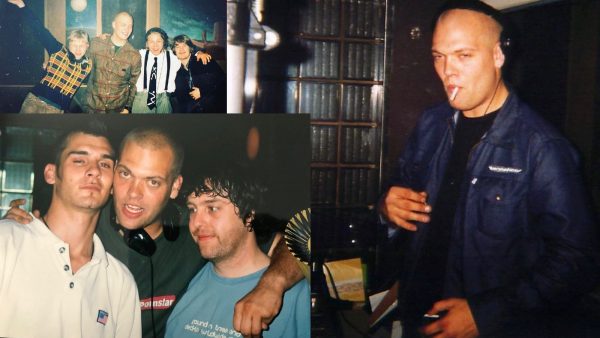

O: Geir and Omar V were the first residents and after a while I brought along Truls and Robin. Torbjørn Brundtland from Røyksopp used to be there all the time before they moved to Bergen. Even Fardin (Faramarzi) was involved in the beginning. He was on the door primarily, but he would also DJ from time to time.

g: And Per Martinsen (Mental Overdrive). Besides DJs like these, we also started booking foreign DJs almost straight away.

O: We booked the Paper Recordings guys early on, Kenny Hawkes and Luke Solomun. Then I met the Idjut Boys at Bar Rumba in London. People started talking, a community of DJs across Europe. We got to know Jori Hulkkonen, Jesper Dahlbeck and Stephan Grieder from Svek.

g: They would’ve just taken the bus from Sweden. I remember it was a really really big thing at that time, because Svek was really hot, and later they would licence one of their songs to the Glasgow underground mix I made, they’d never done that before.

O: At that time most DJs from England were like 200/300 GBP. I mean we did a lot of swaps, so people wanted to come to Geir’s club and Geir got invited back to England, and the same with me. It was all by telephone or fax and quite a few of these people I met in record stores in London like Atlas, Vinyl junkies and Black market.

By the summer of ‘96 there started to be a buzz and by the autumn of that year it was really picking up. We started getting 100 metre queues outside on most nights.

The crowd was made up of older hippy-like free thinkers with a mix of the “It” crowd, like young photographers, creative people and dancers; your alternative club people. It might have looked the same if you went to Moscow or Italy at the time; a small club scene with cool individualists.

g: We were just distributing flyers and word of mouth reached everybody. Even though it was an Internet cafe, ironically there was nothing online.

O: I also had a radio show on NRK from ‘93, when people still checked the radio for new music. It was a good time to be on the radio. Radio was mostly for people outside of Oslo; people in Oslo went out on Saturday nights, they didn’t sit at home and listen to the radio. After a while people came round from all over the country to check out Skansen.

They adopted it quite well. It was such a small place that if you didn’t like it, you left, because you had to be part of the party to have a good time. It wasn’t a place to stand in the corner to observe.

g: It was a very intense kind of feeling.

O: It was a small room and you were on top of each other. A lot of the people made new friends there.

g: It was a busy time for that end of Oslo too. Jazid was in Pilestredet and Headon was in rosenkrantz gate so there was this straight line going through them.

O: There was basically 500m between the 3 main clubs in Oslo. Headon were doing more funk stuff. Jazzid was so much more trip-hop, downbeat drum n bass. So it was easy for Skansen to be more House based, and have a strict difference between these 3 venues. We had a kind of a deal in the beginning not to push each other.

g: I played at both Jazid and Skansen for a while, when it was still ok to play House music at the first one.

O: Geir had your Fridays and I had my Thursdays. Geir and Cecilie were taking care of Saturdays and then we had some weekends together where we were co-operating and bringing in guests.

The bookings were still dominated by that sound in France, of motorbass, Étienne de Crécy, paper recordings, and Erik Rug. You had that London scene, And then you had that more high energy Chicago and New York type of House sound, which was run by Classic , but then you had a local sound too that started to get recognition abroad too.

g: Yeah, that Erot and Bjørn Torkse sound, called Skrangle or whatever.

O: Skrangle, means sloppy in a way, which is not strictly 4-4, but more sloppy. Bjørn or Erot basically in the way that they move and also play.

g: It was a term we used here in Norway, but it is not an internationally recognised word.

O: We didn’t use that word at all back then. We could say that something was Skranglete if it wasn’t really accurate. We both came from sequenced music, which was not the case for Skansen, which was more open.

g: The Idjut Boys stuff kind of encapsulated that mood.

O: Meaning more dubs and echoes, and percussion that was off; a bit more live sounding. We weren’t really thinking about creating a sound or anything, we were in the middle of it.

Of course loads got influenced by it, with all these Jazz musicians coming in through Bugge and Niels Petter, and they all started doing electronic albums after being at Skansen for half a year.

g: It was just something in the air at the time. The ones playing in the scenes we admired abroad, were also the same people we were booking so it felt very connected.

O: We were basically all stroking each other’s backs and trying to make our way through the scene. I guess everybody was doing the same thing; whether it was Sheffield, London Stockholm or Paris and in Oslo it became this fluid thing between us and Bergen.

We had lots of contact with Mikal Telle, and we knew all the players in Bergen, but mostly it was Bjørn, Erot and Kahuun. Erot actually played his first gig at Skansen

g: That was a legendary set.

O: Annie was with Erot at the time and they slept on top of my records. They stayed for a week, just eating spaghetti and ketchup. They didn’t have any money, I didn’t have any money, nobody had any money back then.

Tore (Erot) was only just starting to make music. I actually met him at a rave in Drammen before and then Bjørn told me about him and then we brought him over.

It was one of my most memorable nights there, besides another with Omid 16B playing live. This was SuperReal’s first birthday and Omid was actually an act that fitted more into Footfood’s night. But since it was the birthday, we had Geir as part of the party. It was amazingly good.

g: I can’t remember that specific night, there are just too many.

O: There were some great nights with the Idjut Boys. Back then it was only vinyl and they went a lot to New York. They were a few years ahead of us when it came to weird, hard to find stuff. Also some mad nights with Simon Lee from Faze Action.

This was at the height of Paper Recordings, when they would release a 12” every ten days and most of their tracks went into the top 20 of club charts in that time. They also released the Those Norwegians LP, Kaminsky Park in ‘97.

g: It was very kind of hot for a while with Ari B and an article in the face. For its popularity however during this time, it was kind of hanging in the air the whole time. Per and those people weren’t really that good with the paperwork. There was always something threatening the existence of the club, but they always kind of got it back on track.

O: And then in ‘99 it just stopped.

g: I had just finished the Glasgow Underground Skansen mix, and it was just suddenly closed one day. It was a really big thing for me to do this mix when it came out. We were going to have this release party at Skansen, but it lost its licence on the same day.

O: Then the indie rock scene took over from ten years of House and Techno in Oslo. Suddenly Hip Hop started being played in more venues. The years that followed from 2000 – 2003, you had to be more versatile as a DJ. I had to play so much different stuff to get gigs. Uptempo Hip-Hop, like Timbaland instrumentals and mix it with House. And then you had Mono and Baronsai coming up which had a different profile.

g: I actually moved Footfood to Baronsai. It was really hip to be around all the places in youngstorget so it was suddenly very far for people to go down to Skansen. We tried to re-open it, after that but it didn’t last very long.

O: The main years for Skansen was early january ‘96 til late ‘99 with the same ownership. We were young as well.

g: I mean, I was 23 in ‘96 when it had been open for a year.

O: We were like kids. We felt like grown-ups, like we were important.

g: But, we weren’t so grown up.

O: I made loads of friends. Loads of us got bigger through Skansen.

g: There was a generation that disappeared with Skansen

O: It was the first experience for quite a few. It was magic for that period of time, it’s always hard to recreate something like that. Most of the people that went out at that time were 28 by 2000 and moved on in their life, most of them except for us and a few others (laughs). Everyone that tried to be there after that tried to make their version of it.

g: Nothing has really worked though. It is so difficult to do something else down there because everybody will always want to compare it to Skansen and that time and era in club music in Oslo.