2007 was electronic dance music’s year. The emergence of what would later be dubbed blog house; the apex in the rise of bedroom producer; the accessibility to new music due to the fairly new connectivity of social media; and the technology of DJing at the time, meant anybody with a laptop could establish a club night in some rundown bar with a world of music at their fingertips, usually dominated by a four to the floor beat.

It was all about new music, and from Dubstep to “Berghain” Techno, you couldn’t escape a drum machine (or more likely a VST version of said drum machine) for fear of being ostracised by your peers for being uncool. It was the pinnacle of the hipster era, where being a dickhead was cool and collecting records started becoming en-vogue again.

It was hardly a time for one of the most iconic cosmic Rock records to be released, and yet it is the year of Map of Africa, a collaborative one album project between DJ Harvey and Thomas Bullock. Rock music was definitely not on anybody’s radars at that time and besides Rock-leaning electronic outfits like Hot Chip and LCD soundsystem, the age of Indie rockers in skinny jeans making 60s and 70s inspired garage rock was clearly coming to an end and like James Murphy said in 2005, people were selling guitars and drum kits for turntables and swapping dirty rock clubs for gleaning dance floors running expensive sound systems and even more expensive DJs.

Pitchfork’s 5.2 out of 10 review of the LP in which Mark Pytlik wrote that ”Map of Africa really doesn’t have much in common sonically with dance music at all” should infer a little about the zeitgeist of the time. Even for all of Pitchfork’s indie Rock affiliations, a barebones Rock LP, was completely out of touch with what was happening at the time, especially an LP that went back, rather than forward, and yet Map of Africa still stands its own ground today in many a hallowed record collections.

All the ingredients for success with a recipe for failure

DJ Harvey (Bassett) and Thomas Bullock were at the top of their game when they started making Map Of Africa. Bullock had just walked out on A.R.E Weapons, who defined electroclash in NYC, and had started working with Eric Duncan on the highly successful Rub N Tug production unit and DJ crew. He had garnered a reputation as a producer for his noisy synthesiser exploits in A.R.E Weapons, and by the time of Map of Africa he had just finished work on a new studio in his upstate New York retreat.

DJ Harvey was and is a legend behind the decks, a rock n roll character moulded in the likes of those sixties and seventies legends of excess. You don’t get dubbed the Keith Richards of dance music likely and legend preceded Harvey wherever he went. His first 7” as part of punk band Ersatz was played on John Peel, before he moved into dance music, playing a fundamental part in nineties rave culture as part of the Cambridge-based Tonka DJ crew and party-set and as one of the first residents of Ministry of Sound. In the mid-2000’s he was exiled in the USA over some visa complications, staking a legendary claim around LA, New York and Hawaii’s underground, way before making his grand return to the international scene in 2010.

Bullock and Harvey had known each other since the Tonka Cambridge days, and had met when the much younger Bullock joined the fray. “We were pretty great together,” remembers Bullock in a Loop interview. “I think it was because I skated and not many other people did. All his other mates were gothic junkies. He was a B-Boy.” Bullock and Harvey had been playing or making music on and off together since. They even had a band, which A.R.E Weapons kind of dissolved, but when Bullock left, it provided the impetus to make some music together.

“Harvey was really pissed off that I had worked on A.R.E. Weapons,” says Bullock so when ”when A.R.E. Weapons was done for me, the only thing that Harvey said, was ‘Cool. Now we can have our band.’ I said ‘Cool, let’s call ourselves Map of Africa.’”After years of living in different places, they ended up in the same country and decided to make music together, and Bullock’s studio retreat would set the scene.

Map of Africa “ended up being a rock record” according to Bullock in the Loop interview, which suggests that perhaps there was no intention to make a rock record and that could have something to do with the context of it all.

DJ Harvey had been stuck with the generic Disco tag for some time, which is not necessarily accurate for a DJ of Harvey’s calibre and his extensive musical palette from Punk to House music. “For so long I’ve been associated with dance music which can be very tracky,” Harvey told RBMA in 2007. It seems Map Of Africa went some way in trying to discourage this tracky association, allowing the artist the freedom “to be able to express myself through song(based)” formats. Secluded from the DJ and Disco “scene” in their remote retreat, Harvey and Bullock couldn’t be further removed from their alliances and naturally surprised everybody with a record that didn’t merely buck a trend, but hardly acknowledged the existence of the word.

In that universe they created on the one and only LP they made together it was like the seventies never concluded and synthesisers had arrived like spaceships from an alternative dimension, and their rendition of the opening track “Black Skin Blue Eyed Boy” arrived like a steel-toed boot up the arse of a zeitgeist.

Disco Punk

“Black Skin Blue Eyed Boy” was originally recorded by Eddy Grant and The Equals in 1970 and it was very much ahead of its time, with a four to the floor syncopated beat and the kind of thin, polished arrangement that would later go on to define the Disco of that decade. It was a proto Disco track and Eddy Grant’s version of the song became a favourite amongst DJ luminaries Francis Grasso at the time, a kind of proto-Harvey character who is widely considered to have invented beat-matching.

Map of Africa’s version of that song couldn’t be more different. The bare-bones nature of Bullock and Harvey’s arrangement which is fortified in the quarter-measure kick stomping out an emphatic groove. “We really rocked a groove” says Bullock in the Loop interview, and it’s that groove that grabs you and refuses to let go through the 14 tracks of the LP. It’s accentuated by Harvey’s gruff voice as he breaks in with the opening line, “black is black” in an ardent Rock chant for the ages. According to Thomas Bullock, he and Harvey auditioned eachother for the role of singer with Bullock acquiescing to Harvey’s alpha-dog snarl, much to the album’s advantage. Even though Harvey jokingly refers to it as his attempt at Karaoke in that RBMA lecture, much of the LP’s appeal lies in Harvey’s voice which floats somewhere between snarling alto of Lemmy and the whisky sonorities of Joe Cocker or Jim Morrison.

Map Of Africa turns Eddy Grant’s original into an anthemic Garage Rock tribute, slowing it down to a point where Bullock and Harvey’s ability “to rock a groove” just sticks with you as you ride out the opener into “Gonna Ride” and “Dirty Lovin”, but by the time you get to “Creation Myth” it becomes an album of two sides.

Indulgence over excess

Bullock told SUP Magazine in 2007 that “Map of Africa is the most serious meeting of our minds thus far.” While they’ve played together in various bands in the past, it seemed that they solidified something on the album. Not quite a concept, but certainly a very intricate body of work, that was a direct product of the different factors that encouraged its creation. “We’re just trying to have a real nice time,” Harvey told RBMA and according to Bullock they were getting through the album at a rate of a song a day in his studio. They were fortunate to pick up a deal from Whatever We Want records at a time when bands were still getting advances through the label, which according to Harvey in SUP gave them the “freedom to totally indulge ourselves.”

It allowed the duo to draw out more of those balearic influences they undoubtedly inherited from the UK. It’s an album with “two kinds of music,” confirms Harvey in RBMA. One part of it is more “stompy, rocky” while “the other half is more cosmic, balearic and melow.” If it had been an all-out garage Rock affair I doubt that it would have had the same kind of effect on the DJ community as it would come to have. Listening to Harvey’s 2014 LP, Wildest Dreams, which intones a similar voice in a kind of west-coast surfer Rock dialect, and you soon notice it is lacking that crucial cosmic element that made Map of Africa so much more than just a Rock record.

It’s between “Creation Myth” and the title track that the nature of the album shifts into a record with a dual personality, while maintaining all those crucial elements that make it sound like a cohesive album. From the stompy rock of the first three tracks, “Creation Myth” slips into psychedelia like a lysergic dream, created from the decay of the other tracks of the album. The staccato groves of the openers disappear into the ambient swells of the guitar and pads, with the album accommodating several moods from that point on.

Let’s get physical

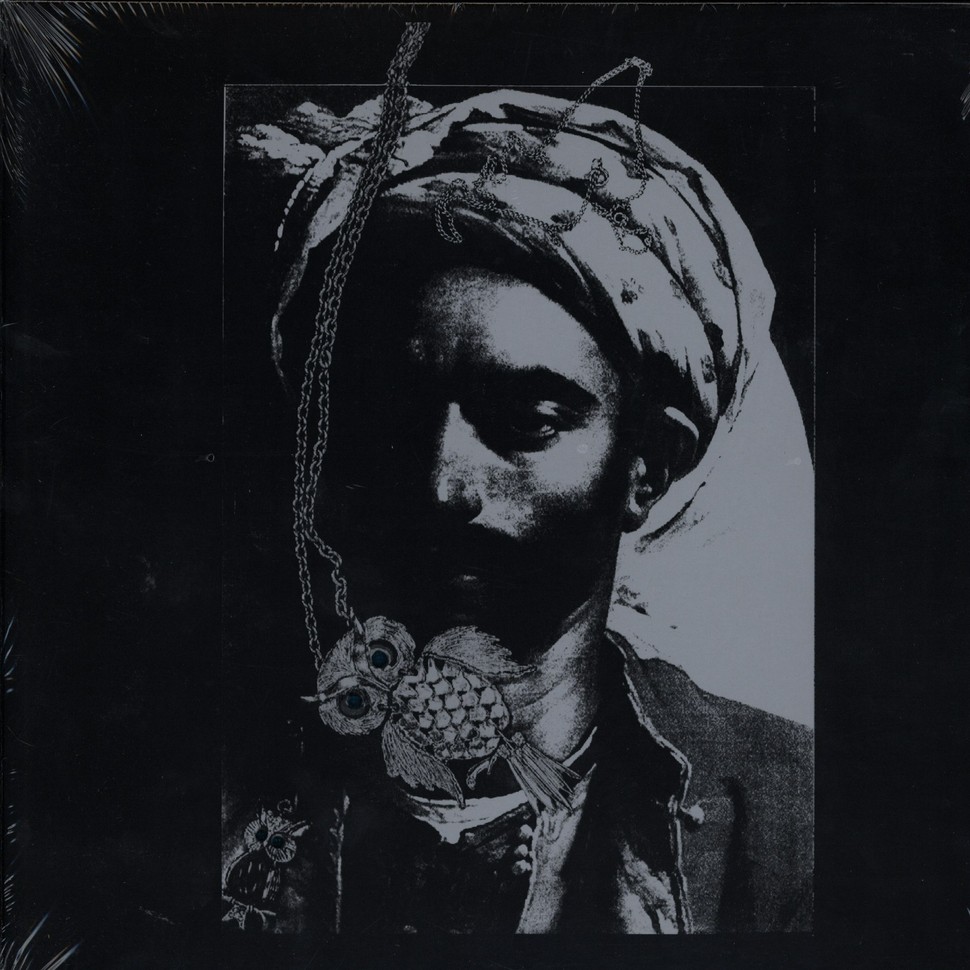

The name “Map of Africa is a sex stain left on a bed” explains DJ Harvey (like it was needed) on an RBMA lecture from 2005. It ties in with the perverted persona of the DJ Harvey character, undoubtedly born from the same place as his label “Black Cock,” but it’s in these sensual moments on the record like the title track, “Bone,” and “Freaky Ways” where the album offers more than just a flat-footed beat. Channeling the vast expanse of their musical dialect and perversions into music, they manage to harness the explorative nature of their musical spectrum into an explosive physicality.

Harvey and Bullock played all the instruments on this record, and although Bullock spent some time editing the raw recordings into those insatiable grooves, it is exactly this hands-on approach in which the album’s charm lies. From Harvey’s distinctive voice, the live drums, squealing guitars and the boogie simplicity of the keys, the album places you right there in the barn, jamming out with the pair as they play.

“I like to hit something,” Harvey told SUP about the recording process of this album. It was about how the “sound moves through the air before it hits the machine and becomes digital,” and it’s something that they managed to retain throughout the post-production phase; the format of the album; the themes that course through the lyrics like “Dirty Loving;” and which eventually arrives at the listener in all it’s brazen wonder.

An elusive moment

In many ways it was the exclusivity of the format and the limited release that made this album such a white whale for collectors. When DJ Harvey did the RBMA lecture around the time of its release, he had one of only a few copies of the second single, he remarked with amusement. The label Whatever we Want lived up to their name, and with a limited pressing of the record, it seemed more about capturing an elusive moment between two legendary figures, than releasing a record. Not much is known about Carlos Aires, the man behind the label that facilitated record, but it is rumoured that he was a formidable DJ talent in his own right, who works in film today. It seemed his only aim was to make this record happen and so it did, and today it remains enshrined in DJ and electronic music lore.

Although the two musicians had worked before in the past, this record was very much of its time place and a serendipitous melding of various factors to make the record happen in the first place. It’s success was of course in part due to DJ Harvey and Thomas Bullock’s reputation, but it remains an isolated example to this day. Although there is a second LP apparently ready, the fact that it has never seen the light of day also encourages the mysticism that surrounds the album. “The songs are recorded and really quite good,” Bullock told the Loop back in 2013, but nothing has ever come of it.

About a year after Bullock’s statement, DJ Harvey would release “Wildest Dreams,” an album that played in similar sonic hues to Map of Africa, but never truly captured the same mood of Map of Africa. It’s very likely that many of those songs might have even come out of some Map of Africa sessions, but for the most part it falls way off the mark of those integral moments that made its predecessor such an anomaly on the DJ circuit and collectors scene when it was released. Map of Africa is a perfect moment captured at perceivably the wrong time, but to great effect. Like a great DJ that is able to manipulate an audience around a song they won’t usually dance to, Map of Africa achieved exactly the same on the electronic music landscape when it was released, and that’s part of the reason it lives on in infamy today.

Today the record is not that elusive with original copies going for about the same price now as they were new, but it’s more about what it represents in spirit, that very same notorious rebellion that has made DJ Harvey and Thomas Bullock such legendary figures on theDJ circuit. Whether it was for the characters that constituted the band, it’s fairly limited press or the fact that it was released at one of the most inopportune times for a rock LP, Map of Africa stands as an iconic LP today.