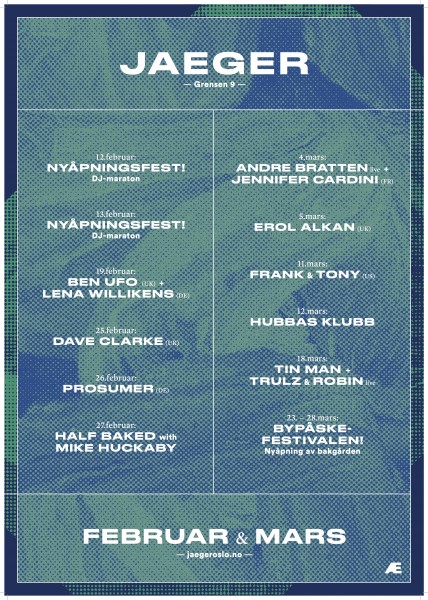

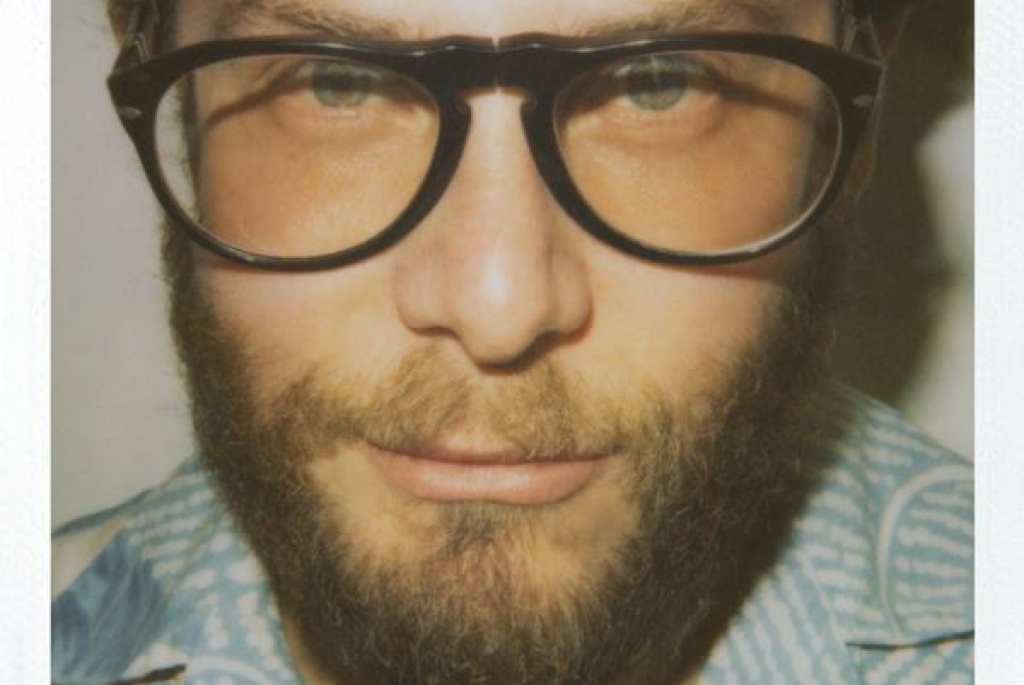

This story originally appeared in our blog in 2018 and we thought we’d take another look at it ahead of Ben Sims return to Jaeger in a couple of weeks for Bypåskefestivalen.

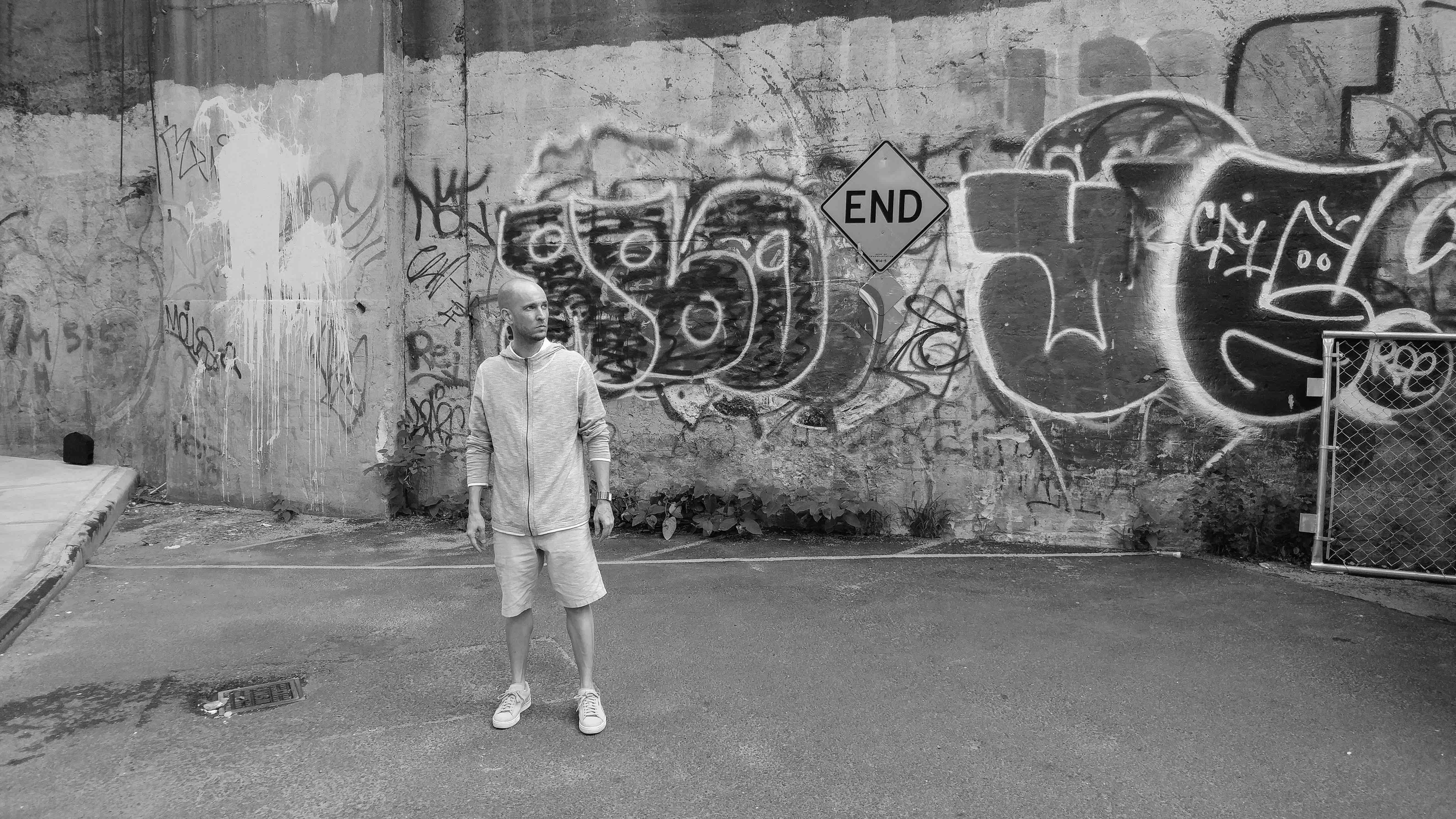

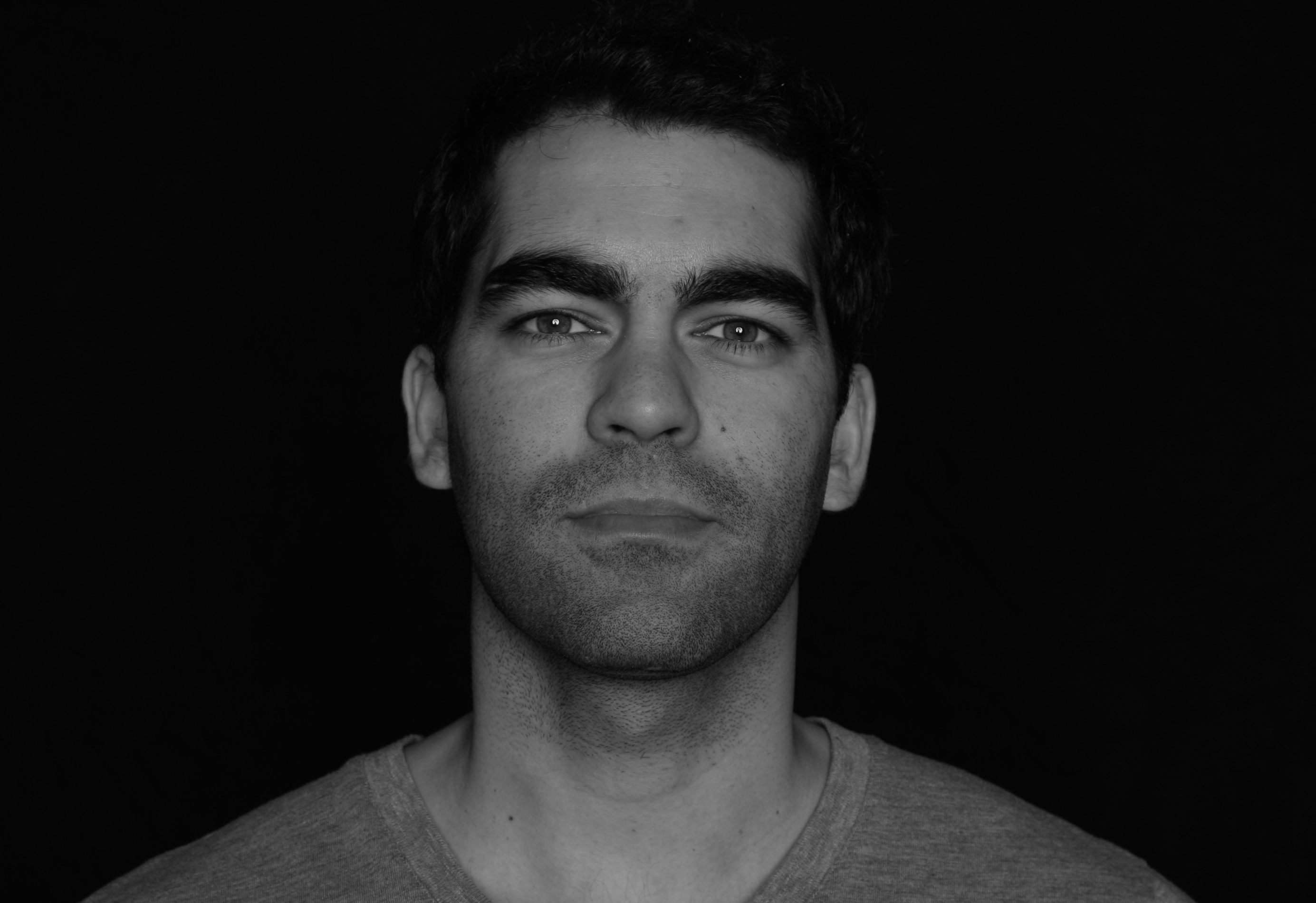

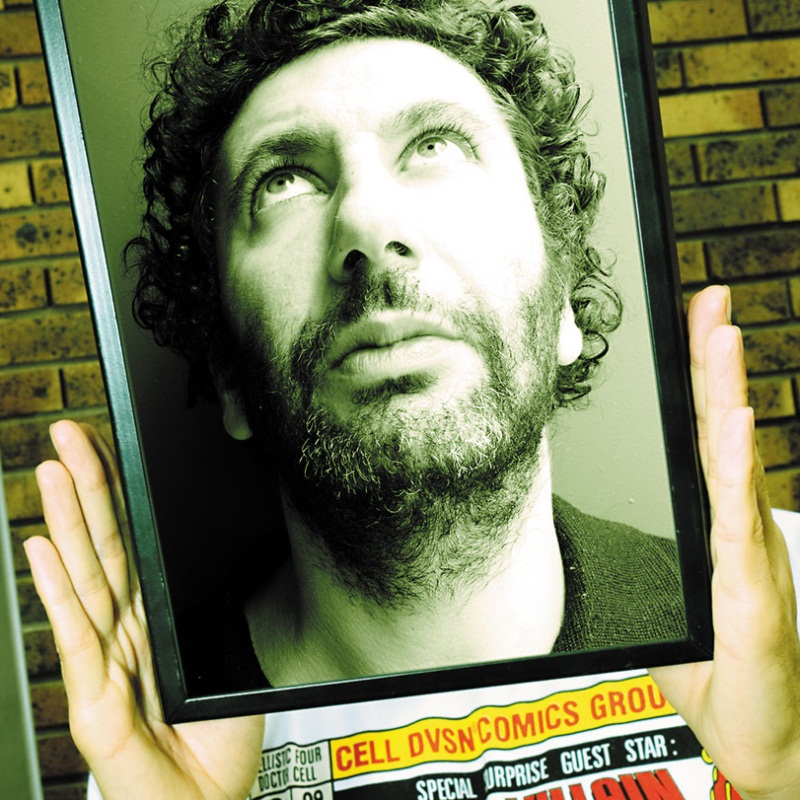

Where do you start a story on Ben Sims? A veteran of the Techno scene, he’s been working as a producer, DJ and label owner on the extended Techno circuit for nearly as long as the genre has existed. He’s been a stalwart facilitator for Techno and House since the nineties, an unwavering presence in the booth, both physically and metaphysically.

Do we start a story of Ben Sims at the beginning, back at the moment of conception where a young Hip Hop enthusiast turned from making mixtapes in the bedroom to the new exciting sounds of House and Techno’s golden era? Or do we turn the clock back to the late nineties where Ben Sims went from a DJ to producer releasing his first records through his own labels, Theory and Hardgroove and later for the likes of Tresor and Drumcode?

We could start at either of those barbs on his extended, intertwining musical timeline but his most significant contribution to has been in the attitude and ideology he pursues as an artist , DJ and label owner. His debut and only LP, smoke and Mirrors on Drumcode; his perpetual determination for a hard-edged sound even during the epoch of minimal Techno or Tech-House; and his refined sense in the booth as a DJ all comes from a core belief what Techno is and he is absolutely resolute in his singular pursuit.

Whether he’s harnessing all that experience in his unique style as a DJ, piecing together fragments from the diverse corners of electronic music in sound collage only he could see or making bold dance floor cuts as an artist through his various aliases like Ron Bacardi, Ben Sims has remained steadfast in his ideological view of Techno.

Without any hyperbolic implication, Ben Sims is a giant amongst men in the world of Techno. He’s always pursued a singular vision of Techno and as it moves in and out vogue, he wavers little from the path of the golden era of Detroit, only updating elements of his sound and tracks in his booth with the natural passage of time. “I’m usually older than the promoter and the person that owns the fucking building,” he muses in a gravelly working-man’s southern-English accent when we call him up for an interview, and yet he still packs a room and leaves an indelible mark whenever he is in the booth.

Ever the restless figure, in recent years, he’s established a new event series turned label in Machine; brought back the label Symbolism; established his NTS Run it Red show, which has been going strong now for 45 episodes; and started a new project with Truncate as ASSAILANTS, all while still releasing music as Ben Sims on labels like Deeply Rooted and DJing week in and week out.

It’s a very productive time for Ben Sims. After releasing their first single as ASSAILANTS this year, he and Truncate are “working on a follow up EP which is 60% done.” It’s a project Sims says “happened quite naturally” after the pair had been friends for a few years and played together and remixed each other’s records. ”It’s not something we’ve placed any pressure on or stuck to any kind of plan,” he says “It’s just something we enjoyed working on together.” They released their first single via the new label Obscurity is Infinite this year and hope to release the next some time in the spring of next year, but while he is currently enjoying working as an artist, he’s also returned to the role of label owner through his dormant Symbolism imprint after taking a hiatus from the record industry.

Although Sims closed the chapter on his Theory label some four years back, he did “miss running” the label. “It’s great to put a bit of focus back into a record label again,” he says and releasing artists that he’s “really excited about.” With a few releases primed for this year, he chose Symbolism because it “had always felt unfinished,” a “victim of distribution companies going bust.” He couldn’t just leave it like that and wanted to “bring Symbolism to a better kind of conclusion,” but today it has taken on a life of its own and it looks like it’s here to stay.

Running labels “feels like an important part of it” to Ben Sims, and he has his fair share of experience at that level, but it’s particularly as a DJ where he’s etched his name into the electronic music legend.

It’s in that spirit that he and Kirk Degiorgio established Machine. “It was his idea,” says Sims about the concept. “He was very passionate about music as well and we have similar backgrounds.” In 2011 they were both getting really “excited about modern Techno,” and started hosting “low key parties, with a focus on only playing new and unreleased Techno.” The event grew and traveled, as they got more “ambitious” with their guestlist. “Somewhere in there we did three releases with music from us that we just tested out at the parties,” but Sims insists it was never intended to be a label, but merely an extension of the club night.

It makes sense that the next release on Machine will be a 50-track compilation and Ben Sims mix titled, “Tribology”. It frames the context of the club night, and in Sims’ opinion “it helps put (Machine) into the consciousness of those who haven’t heard it before.”

It makes sense to pick up Ben’s story here at this moment, because over the last twenty years, he’s deviated little from the same purpose that informs a club night like Machine, his ASSAILANTS project and the rebirth of Symbolism. That’s the context to which he returns to Jæger this week, and it’s with that looming in the background that we called him up for a Q&A session to talk about DJing, for a view from the other side.

*Ben Sims plays Frædag x Filter Musikk this Friday.

The last time you were here you were here as Ron Bacardi. What are your memories of that night?

I was playing outside in the terrace and it was kind of a light-hearted vibe with people drinking and chatting. It suited the music I was playing. It was nice to have the balance of doing something different now and again.

Listening to your Run it Red NTS podcast as Ben Sims, it’s very eclectic and there are often elements of House in there. Why do you feel you need to split your aliases in that way?

There are some places and crowds that are open-minded, and want to hear DJs mix it up and incorporate different genres and styles. But I’ve found over the years, unless I’m specific about what I’m going to do, people get a bit disappointed and they expect to hear peak-time Ben Sims all of the time. I guess that’s more implied in places I’ve been going a long time, like Spain and Holland and I understand that. Having a different name for it does allow me to be a little bit self-indulgent, and as Ron Bacardi I can play House and I can play Disco, and go off in tangents. I like my Techno sets to be littered with different styles, but having another name allows me to go further than I ever could before as an extension of a Techno set.

Do you think it has only happened more recently as Techno has become a little more restrictive from the nineties when House and Techno were a bit more fluid?

No, not necessarily. I come from a very mixed musical background and earlier I could play a lot more different styles in a set, but that’s because I wasn’t on at peak time. You get more room to experiment and I used to try and push it as far as I could, and when you slide into headline clubs, it is difficult to play House for an hour or play some Disco tracks. The times I did try something different and it was billed as something like a Ben Sims Acid House set, a Disco set, or even a Drum n Bass set – I’ve done a few of those – there will always be some people that would be disappointed because it had my name on the flyer and they weren’t getting what they wanted.

Do you think your releases on staunch Techno labels like Tresor and your own Theory label, might play a hand in that you feel you have to abide to that sound, and give your fans that kind of experience?

There will always be an element of that. I always want to represent what I’m into, what my vision of Techno is. That hasn’t really changed a lot since I started making it and playing on the circuit. I have a certain idea of what Techno is and my favourite sounds or groups within it and the core of that hasn’t changed at all.

Could you describe that sound?

It’s energy, but not just because it’s fast. It’s some kind of drive or groove to it. I always used to refer to the sound as hardgroove. It’s still got to be funky, and have a raw element. A lot of it tends to sound like it was done on a bedroom setup – not over-produced. I like a different styles, but usually it’s quite stripped back and rhythmic. It’s stuff that locks you in a groove and you can get lost in it. It can’t be disposable and not just hard for the sake of it. It needs to have some sort of funk or groove.

Harking back to that original Detroit sound?

Yes, that’s still where my inspiration and excitement for Techno comes from, the first wave of Detroit stuff. It’s not necessarily the music I make, but that’s still what inspires me, and as Techno has changed and different countries and cities have become the focal point of the scene, I haven’t really changed. As this generation is looking to the sound of Berlin, I’m not really doing that, because Techno is Detroit.

It’s exactly because of Berlin that it’s enjoying another wave of popularity at the moment, but as a veteran that’s seen it go through various phases of popularity, do you feel that you have to adapt to the surroundings at all?

There’ll be be new sounds or fads that would come along that would interest me, and I’ll incorporate new stuff, but I won’t just jump on it because that’s what people are excited about. It has to interest me. And I think the reason, I’ve been doing this for twenty-odd years is that people appreciate it and that might also be why some people don’t like what I do, because I stick to the same sound. I play the stuff that I like within Techno, and as long as I’m playing the stuff that I like it’s hopefully contagious.

Just looking at the tracklists for Run it Red I know that you go through a lot of tracks during the course of a mix, but it’s not just about playing one track after the other it seems, but rather piecing together little musical vignettes to create this massive mix. What is your thought process when it comes to putting those tracks together for the sake of the radio show and this upcoming Tribology mix for Machine?

I’ve only realised this recently, but I think I attack it like a puzzle that needs to be solved. There’s an element of me trying to squeeze in as much possible, to incorporate as much as I can. It’s similar to the way I do club set where I’ll just put in the best bits of things. I’ll have a definite starting point and end point and just piece it together form there.

With the Tribology mix, it was just going to be a compilation, and me mixing it was a bit of an afterthought. It was about getting the artists involved that I play regularly and guests that have played at the Machine parties to contribute tracks. It was a compilation to support the tour and something physical for the parties we were doing. Then I thought it would be nice if I mixed it, and then from that point it needed to turn from a 10-15 track compilation to enough tracks to do a mix that was worthwhile doing. That was going to be 30-35 tracks and then it just spiralled and it became 50.

Yes, I very rarely play one track on its own, and that’s how I attack putting the music together. That’s the challenge for me, to get as much together and for it to make sense and for it to flow.

Does that mean there’s a lot of planning that goes into something like that Tribology mix?

As I was approaching artists that were going to be involved, unconsciously I was already planning some order. When they started sending tracks over some were like “o, well, here’s five choose one” and I was like “actually I could use all of it.” I was solving the puzzle of putting it together as I was compiling it. Like a DJ set, I always knew where the start was going to be, where I want to be half-way through it and what possible ending there could be, although you don’t always get there.

You mentioned some similarities to your club sets, but how does mixtape or your radio show differ from a club set, do you miss that physical energy of a club in those kind of sets?

I do tend to feed off of the feedback from people. If I’m going in a direction that’s progressively harder or intense, that’s different according to the crowd. I don’t always do that with mixes or podcasts, because it’s not always appropriate. I do approach them in a certain way however as in the way I mix is the way I mix. To a certain extent it doesn’t really matter if someone is in the room or not. I do tend switch off from the surroundings a little bit, and sometimes I’d realise; “fuck I hadn’t looked up for ten minutes,” because I’m so focussed to piecing it together that I forget that I’m doing it for someone else.

Is it focus from being busy with your hands or focussing on the music?

I think it’s the latter. It’s my escapism and my way of relaxing and the only thing that’s important is the next record your mixing. In the end it’s a simple life and does get you away from the stresses of the world. You can really get lost in it and I do get off on that.

You must find yourself playing to younger and younger audiences, and just from my own perspective it feels to me that there’s more of an immediacy to this next generation’s needs. Do you feel you need to adapt to that immediacy and intensity of youth in your sets today?

I’m not on the dance floor anymore, but I used to be a lot through my late teens and early twenties, which is the crowd I’m playing for now, and I guess I just kind of remember that. It’s helpful to remember what it is like to be on the dance floor and all pumped up. It’s something that I’ve never forgotten, and sometimes I might approach my set by going in a little bit heavy at the start, just to grab their attention and then back off a little bit later. Whereas if I went with my plan it would be to just ease them in. It’s a bit tactical. To some extent I do miss it, otherwise I wouldn’t be out there doing it for other people.

I guess that’s what keeps the music pushing forward, not just the new music, but a new interest in the music.

Yes. if I were to play to a room of people my age, just scratching their chins that wouldn’t be much fun. You need the injection of new life. Unless you get involved in the scene or step the other side of the booth, clubbing has a shelf life and people drop off.

Where do you see Techno going next if you could gaze into your crystal ball with all your experience?

(Laughs) It feels like it’s dropping off in popularity and that’s ok with me. It doesn’t always help when it’s at its peak of popularity, it does water things down a little bit. That doesn’t mean there isn’t more work out there for a short period of time, but that’s not really promoting longevity, it becomes fashion.

I do prefer it when it’s not in that peak moment, because the crowd is there for the right reasons and the people that are making it are doing it because that’s what they are passionate about, and it feels that period is what we’re slipping into now.

After minimal Techno and Tech House was so massive, and Techno was the underdog, it kind of swapped around and I think that’s going to go away again. I’m not really too sure to what, I thought it might be Trance but that doesn’t seem to be happening. I’d be interested to see where it goes, but I doubt I will be following it.

And one last question Ben, before I ‘ll let you go: what are your expectations of the set at Jæger for this weekend?

It’s a great space. It’s been a couple of years ago that I played there and I didn’t really know what to expect. It’s great playing somewhere for the first time, but I do like to go back armed with the knowledge of what it’s like and what kind of things work and what don’t and feel a bit more comfortable with the setup. I’m just really looking forward to it.

Tell me about going to the Loft.

Tell me about going to the Loft. Did he just play on Blå’s soundsystem?

Did he just play on Blå’s soundsystem? Did you ever talk to him about the peak era of the Loft?

Did you ever talk to him about the peak era of the Loft?

“Drugs, nothing more,” says Tornike, but “when they raided the club, no-one was arrested for dealing drugs and they couldn’t find any drug dealers inside the club, only finding 2 or 3 grams” on individuals. The club owners were arrested too, without a warrant on some overblown claims of obstruction, which never resulted in any charges brought forward, but what happened directly after the raid, was a force of solidarity in a clubbing community that we haven’t seen since the time of the criminal justice and public order act. People like Tornike, who had started gathering outside Bassiani as the police were carting off their friends and colleagues, were protesting the arrests. “We were trying to figure out what was happening,” explains Tornike who “didn’t even know which Police station they took them to” at the time.

“Drugs, nothing more,” says Tornike, but “when they raided the club, no-one was arrested for dealing drugs and they couldn’t find any drug dealers inside the club, only finding 2 or 3 grams” on individuals. The club owners were arrested too, without a warrant on some overblown claims of obstruction, which never resulted in any charges brought forward, but what happened directly after the raid, was a force of solidarity in a clubbing community that we haven’t seen since the time of the criminal justice and public order act. People like Tornike, who had started gathering outside Bassiani as the police were carting off their friends and colleagues, were protesting the arrests. “We were trying to figure out what was happening,” explains Tornike who “didn’t even know which Police station they took them to” at the time.

Working with TB Arthur and people like BMG, do you think It’s changed the way you make music?

Working with TB Arthur and people like BMG, do you think It’s changed the way you make music? Like every DJ out there today you have an agent that takes care of your bookings, but do you have the final say where you’ll play?

Like every DJ out there today you have an agent that takes care of your bookings, but do you have the final say where you’ll play?

The idea of dugnadsånden is also how Ra-Shidi had her start as a DJ. “I just went up to the manager at Circa and asked if I could play there, and he just said, ‘yeah sure’.” Unfortunately, Circa is coming to an end in two months, and Ra-Shidi is hoping Storgata Camping will carry the beacon for the clubbing community, with more reserved bookings but with a bigger impact to attract the larger audience to fill the dance floor.

The idea of dugnadsånden is also how Ra-Shidi had her start as a DJ. “I just went up to the manager at Circa and asked if I could play there, and he just said, ‘yeah sure’.” Unfortunately, Circa is coming to an end in two months, and Ra-Shidi is hoping Storgata Camping will carry the beacon for the clubbing community, with more reserved bookings but with a bigger impact to attract the larger audience to fill the dance floor.

The way you explained it was that the shop, Afro Synth is very much a labour of love for you. Can you tell me a bit more about what inspired you to start and run the shop?

The way you explained it was that the shop, Afro Synth is very much a labour of love for you. Can you tell me a bit more about what inspired you to start and run the shop?

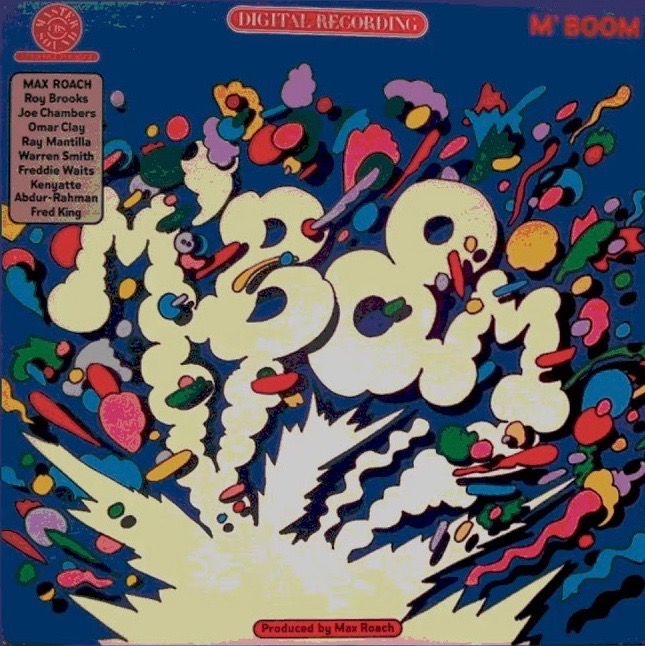

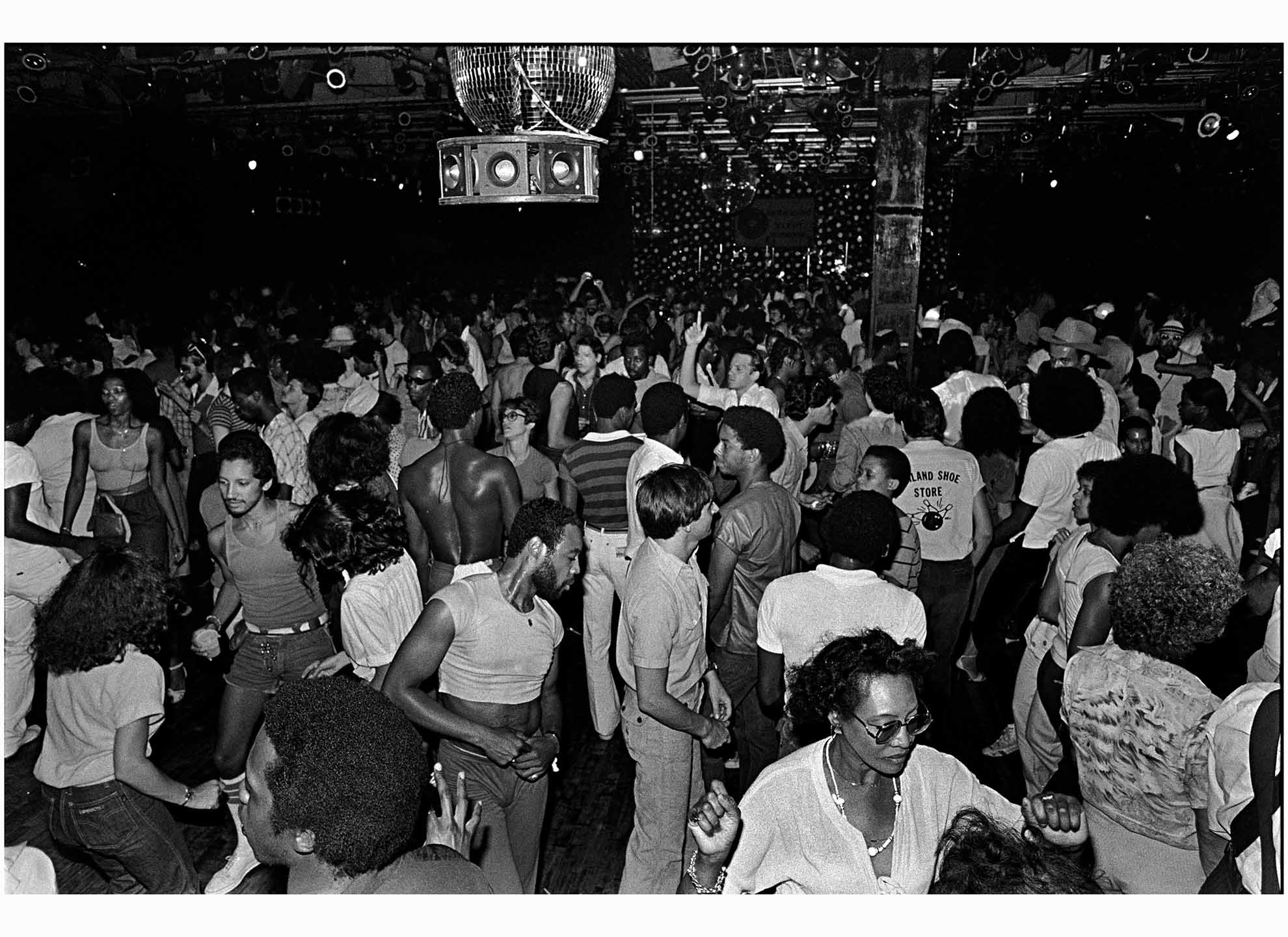

The origins of Techno

The origins of Techno

Mikrometeorittene’s closest descendant is Mechanized World, but offering a much more contemporary approach to the Techno genre. I wonder if it is down to an evolution in their work, but Truls suggests not. “I feel in a way we go in a circle” and redefining the parameters between the projects has allowed them more freedom to explore these more purest forms of their cavernous electronic music interests. KSMISK is a “different vibe in general” according to Robin who also believes they should’ve separated these different sounds “years ago”.

Mikrometeorittene’s closest descendant is Mechanized World, but offering a much more contemporary approach to the Techno genre. I wonder if it is down to an evolution in their work, but Truls suggests not. “I feel in a way we go in a circle” and redefining the parameters between the projects has allowed them more freedom to explore these more purest forms of their cavernous electronic music interests. KSMISK is a “different vibe in general” according to Robin who also believes they should’ve separated these different sounds “years ago”.

Fredrik didn’t go straight from metal to Techno however, but drumming played an integral role in th DJ prowess he displayed early on. Fredrik’s acute ear for rhythm took to DJing very naturally and as a tram goes by in the background by way of serendipitous illumination, Fredrik explains; “I can hear the tram go by and I can immediately feel the rhythm.” He “always knew what DJing was about” because of his older brothers and when he turned 18 and “started partying” DJing came from Fredrik’s desire “to perform music”. He bought “some cheap decks” and through a period of “listening to commercial, shit music” started DJing.

Fredrik didn’t go straight from metal to Techno however, but drumming played an integral role in th DJ prowess he displayed early on. Fredrik’s acute ear for rhythm took to DJing very naturally and as a tram goes by in the background by way of serendipitous illumination, Fredrik explains; “I can hear the tram go by and I can immediately feel the rhythm.” He “always knew what DJing was about” because of his older brothers and when he turned 18 and “started partying” DJing came from Fredrik’s desire “to perform music”. He bought “some cheap decks” and through a period of “listening to commercial, shit music” started DJing.

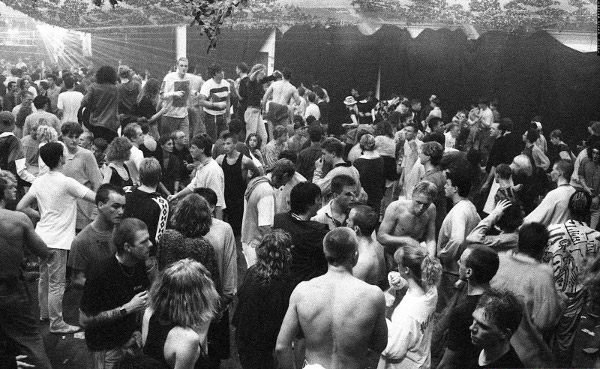

Later that evening after our interview the energy is electric in Jæger’s backyard, peaking at excessive levels, and then suddenly a drop in the bottom end. A wispy melody of some unknown origins builds tension and the whole crowd lurches forward, towards the booth as one. There’s a moment of inextricable pause… it’s nearly silent… and then an exhilarated whoop from the audience as the bass and drums kick back in to the pulse of the dance floor.

Later that evening after our interview the energy is electric in Jæger’s backyard, peaking at excessive levels, and then suddenly a drop in the bottom end. A wispy melody of some unknown origins builds tension and the whole crowd lurches forward, towards the booth as one. There’s a moment of inextricable pause… it’s nearly silent… and then an exhilarated whoop from the audience as the bass and drums kick back in to the pulse of the dance floor.

It seems however that opinion is divided between a high profile DJ like Thaemlitz and the DJs that still work at a local, subcultural level. While a DJ like Thaemlitz is openly opposed to mixed spaces as it heteronormalises the queer aspects of the culture, a younger generation of DJs like Terje Dybdahl and Timothy Wang are embracing and indeed welcoming the mixed orientation of the audiences. As more previously rigidly queer spaces and events like Kaos, overwhelmingly welcome mixed audiences, albeit retaining their queer identity, it appears that a mixed philosophy is becoming the acceptable norm. My first thought was that this might be predicated on a regional aspect since in Europe and the UK this music and its culture was first adopted by a heterosexual audience, but this doesn’t really concur with what US DJ Jason Kendig from Honey Soundsystem told me last year during an interview for Jæger’s blog. He put emphasis on the fact that he and the soundsystem’s “first experiences in dance music were not necessarily in queer spaces”.

It seems however that opinion is divided between a high profile DJ like Thaemlitz and the DJs that still work at a local, subcultural level. While a DJ like Thaemlitz is openly opposed to mixed spaces as it heteronormalises the queer aspects of the culture, a younger generation of DJs like Terje Dybdahl and Timothy Wang are embracing and indeed welcoming the mixed orientation of the audiences. As more previously rigidly queer spaces and events like Kaos, overwhelmingly welcome mixed audiences, albeit retaining their queer identity, it appears that a mixed philosophy is becoming the acceptable norm. My first thought was that this might be predicated on a regional aspect since in Europe and the UK this music and its culture was first adopted by a heterosexual audience, but this doesn’t really concur with what US DJ Jason Kendig from Honey Soundsystem told me last year during an interview for Jæger’s blog. He put emphasis on the fact that he and the soundsystem’s “first experiences in dance music were not necessarily in queer spaces”.

Behind every good DJ is that urge to dig deeper and further, and in Christopher it manifested into an obsessive-compulsive habit when a couple of Joey Negro compilations came his way. “A lot of the House music I listened to came from these tracks” explains Christopher and what started in House music moved into Disco, Soul and Boogie’s more obscure corners. “When I hear a sample that I know from somewhere I get totally obsessed about finding it“, says Christopher. The DJ turned collector after a digging session in Berlin. Stumbling on the originals of some of his “favourite” House tracks, Christopher started exploring the outlying regions of Disco through his sets. “Felix (Klein) did exactly the same thing at the same time” and the two DJs “hooked up and started playing Soul, Disco and Boogie together.” Driven by his desire to find the original of a sample from a House track, and looking beyond the obvious, Christopher “started spending all (his) money on records” and Disco lead to Boogie and of course eventually Boogienetter… but first there was Diskotaket.

Behind every good DJ is that urge to dig deeper and further, and in Christopher it manifested into an obsessive-compulsive habit when a couple of Joey Negro compilations came his way. “A lot of the House music I listened to came from these tracks” explains Christopher and what started in House music moved into Disco, Soul and Boogie’s more obscure corners. “When I hear a sample that I know from somewhere I get totally obsessed about finding it“, says Christopher. The DJ turned collector after a digging session in Berlin. Stumbling on the originals of some of his “favourite” House tracks, Christopher started exploring the outlying regions of Disco through his sets. “Felix (Klein) did exactly the same thing at the same time” and the two DJs “hooked up and started playing Soul, Disco and Boogie together.” Driven by his desire to find the original of a sample from a House track, and looking beyond the obvious, Christopher “started spending all (his) money on records” and Disco lead to Boogie and of course eventually Boogienetter… but first there was Diskotaket.

I was raised in the US, and immigrated to Japan – both of which are cultures with nearly zero federal funding for art and music. So while I understand the logic of feeling entitled to a share of public funds created by one’s tax payments, I also am never surprised when those funds go to the most conservative cultural elements – like classical music halls, or galleries for housing old paintings. Similarly, I never forget futurism’s role as the official art of fascist Italy, or social realism’s role in totalitarian Chinese and Soviet regimes, etc. So both my sense of history and personal experience keeps me from ever being excited by news of countries that fund artists.

I was raised in the US, and immigrated to Japan – both of which are cultures with nearly zero federal funding for art and music. So while I understand the logic of feeling entitled to a share of public funds created by one’s tax payments, I also am never surprised when those funds go to the most conservative cultural elements – like classical music halls, or galleries for housing old paintings. Similarly, I never forget futurism’s role as the official art of fascist Italy, or social realism’s role in totalitarian Chinese and Soviet regimes, etc. So both my sense of history and personal experience keeps me from ever being excited by news of countries that fund artists.

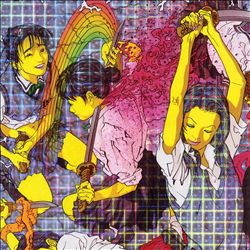

Quarantine made an instant impression on the listener and whether you liked it or loathed it, it was definitely not inadmissible. Critics merely praised it, and accolades for Laurel Halo’s work came in abundance, but public opinion definitely remained divided. “The record’s not meant for everyone”, explained Halo in an interview with the Quietus shortly after the release. “(I)t’s not a pop record in the slightest so I think people expecting that would be disappointed by the vocal tone and production approach.” By the time you get to the second song on the album “Years” you would either be entranced or disenchanted by the beat-less sojourn through Halo’s emotive depths on her debut album. Although Halo’s debut EP, King Felix certainly had ears pricking up everywhere, it would be Quarantine that launched her career, making a vivid statement from the music right through to the artwork, designed by Makota Aira; a colourful and humorous display of Seppuku (ritual Japanese suicide).

Quarantine made an instant impression on the listener and whether you liked it or loathed it, it was definitely not inadmissible. Critics merely praised it, and accolades for Laurel Halo’s work came in abundance, but public opinion definitely remained divided. “The record’s not meant for everyone”, explained Halo in an interview with the Quietus shortly after the release. “(I)t’s not a pop record in the slightest so I think people expecting that would be disappointed by the vocal tone and production approach.” By the time you get to the second song on the album “Years” you would either be entranced or disenchanted by the beat-less sojourn through Halo’s emotive depths on her debut album. Although Halo’s debut EP, King Felix certainly had ears pricking up everywhere, it would be Quarantine that launched her career, making a vivid statement from the music right through to the artwork, designed by Makota Aira; a colourful and humorous display of Seppuku (ritual Japanese suicide).

That was around 2004/5 I guess?

That was around 2004/5 I guess? Roland TR- 909

Roland TR- 909 Oberheim Matrix 12

Oberheim Matrix 12 Roland TB-303

Roland TB-303 Universal Audio Apollo

Universal Audio Apollo A Korg Guy

A Korg Guy

It kind of just happened. I missed working with music, and that was one of the first things I did feel along the trip. I’ve always been heavily interested in making sound recordings. A lot of people that travel, they either blog it or take pictures, and I thought for me, it would be quite natural to make mix tapes of the music we were listening to a lot on the road, and mix it with experiences on the road.

It kind of just happened. I missed working with music, and that was one of the first things I did feel along the trip. I’ve always been heavily interested in making sound recordings. A lot of people that travel, they either blog it or take pictures, and I thought for me, it would be quite natural to make mix tapes of the music we were listening to a lot on the road, and mix it with experiences on the road.  Yes, I’m always collecting music, but it’s not in the way that you think. A lot of people have this romantic idea that I’m going to record stores every week and digging South American gems. First of all it’s not like that at all there, there are not that many record stores there apart from the big cities. I don’t have the space for it and I don’t have a record player on the road. I did consider getting a portable record player, but then I got scared, because half the time you just become a digger instead of travelling and all the other stuff that I enjoy. So I’m just collecting music online.

Yes, I’m always collecting music, but it’s not in the way that you think. A lot of people have this romantic idea that I’m going to record stores every week and digging South American gems. First of all it’s not like that at all there, there are not that many record stores there apart from the big cities. I don’t have the space for it and I don’t have a record player on the road. I did consider getting a portable record player, but then I got scared, because half the time you just become a digger instead of travelling and all the other stuff that I enjoy. So I’m just collecting music online.  You mentioned diversity there and I must admit hew first place I really picked up on an eclecticism in the booth becoming popular was at Trouw. Do you think that was a part of the legacy it left on the DJ scene?

You mentioned diversity there and I must admit hew first place I really picked up on an eclecticism in the booth becoming popular was at Trouw. Do you think that was a part of the legacy it left on the DJ scene?

T

T

There’s a lot of emphasis on a visual presentation. What do you hope the visual accompaniment brings to the releases away from the music?

There’s a lot of emphasis on a visual presentation. What do you hope the visual accompaniment brings to the releases away from the music?

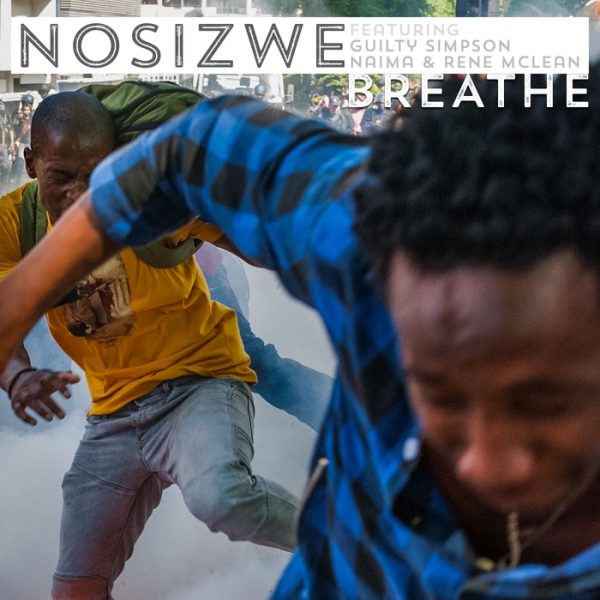

She’s vocal, yet fair on these issues and obviously very conscious of what’s going on in South Africa, and when I ask how much these issues inform her music she offers an example from “In Fragments”, the song Breathe, which she “wrote and dedicated to the student uprising.” The visual accompaniment to the single, a picture of two boys running away from a smoke grenade, which removed out of context looks like two younger men dancing, which Nosizwe brings back to the reality of the situation through her lyrics for Breathe. “I can’t breathe, I can’t see the sun for the light of day”, does not talk of a joyous occasion and after really studying the picture everything falls into its perspective. But as much as that song is about the student uprising, something that “deeply impacted” the artist, it also works in the context of American politics: “That song was definitely a reflection of the politics of SA, but also the United States with all the cop killings and the black lives matter movement.” Political issues are also moments of hope and encouragement for the artist, translated into acknowledgement and a deep seated respect in her music as inspired by the people of South Africa. “Hiya” from the album speaks of feminism and spirituality, not as a “pseudo philosophical” construct, but as a message of an openness that reflects an ingrained history between the people and the earth in South Africa and in the subtext it’s about empowerment. That “song was a thank you to my deeply spiritual and hippy sisterhood” explains Nosizwe. It is a “completely different access and entry to spirituality” for the singer and one that makes it “totally acceptable that you can acknowledge the ancestors on Saturday, go to church on Sunday and smoke weed on top of Devil’s peak on Sunday” with no contradiction between those spiritual elements, much like her album pieces together different, often contrasting things to make a whole.

She’s vocal, yet fair on these issues and obviously very conscious of what’s going on in South Africa, and when I ask how much these issues inform her music she offers an example from “In Fragments”, the song Breathe, which she “wrote and dedicated to the student uprising.” The visual accompaniment to the single, a picture of two boys running away from a smoke grenade, which removed out of context looks like two younger men dancing, which Nosizwe brings back to the reality of the situation through her lyrics for Breathe. “I can’t breathe, I can’t see the sun for the light of day”, does not talk of a joyous occasion and after really studying the picture everything falls into its perspective. But as much as that song is about the student uprising, something that “deeply impacted” the artist, it also works in the context of American politics: “That song was definitely a reflection of the politics of SA, but also the United States with all the cop killings and the black lives matter movement.” Political issues are also moments of hope and encouragement for the artist, translated into acknowledgement and a deep seated respect in her music as inspired by the people of South Africa. “Hiya” from the album speaks of feminism and spirituality, not as a “pseudo philosophical” construct, but as a message of an openness that reflects an ingrained history between the people and the earth in South Africa and in the subtext it’s about empowerment. That “song was a thank you to my deeply spiritual and hippy sisterhood” explains Nosizwe. It is a “completely different access and entry to spirituality” for the singer and one that makes it “totally acceptable that you can acknowledge the ancestors on Saturday, go to church on Sunday and smoke weed on top of Devil’s peak on Sunday” with no contradiction between those spiritual elements, much like her album pieces together different, often contrasting things to make a whole.

A talented young artist from the Ivory Coast, Mr. Sompohi found himself in Rome and then Bergen on scholarships to study sculpture in the eighties. It was in Norway where he would have the significant encounter with Caroline Baardsen that brought Andrew into the world, but it’s also here where he expounded on his lifelong work; delving into the concepts of the African mask through a thoroughly western image.“He found the African mask at Sagene kirke”, explains Andrew, “where he saw the mask in the church door, and he saw the parallel between the African mask and western society.” He calls the concept Gla, shortened from Glalogy. “Gla is the manifestation of the African spirit tradition, African society”, explains Mr. Sompohi during an interlude on Oslo-Harlem, his voice a rich mixture of French accentuation and a booming African tenor. “Gla is the music, Gla is the fine art, Gla is the everything” and the artist focuses all these elements through the aesthetic of the African mask. Visually, the results are striking works of immense proportions with concepts that go deeper and deeper with each idea revealing the next in conceptually dense works of art with the mask as foreground. “There’s always something” says Andrew of his father’s work, work that’s consumed “45 years” of the artist’s life, which Andrew feels he has barely scratched the surface of.

A talented young artist from the Ivory Coast, Mr. Sompohi found himself in Rome and then Bergen on scholarships to study sculpture in the eighties. It was in Norway where he would have the significant encounter with Caroline Baardsen that brought Andrew into the world, but it’s also here where he expounded on his lifelong work; delving into the concepts of the African mask through a thoroughly western image.“He found the African mask at Sagene kirke”, explains Andrew, “where he saw the mask in the church door, and he saw the parallel between the African mask and western society.” He calls the concept Gla, shortened from Glalogy. “Gla is the manifestation of the African spirit tradition, African society”, explains Mr. Sompohi during an interlude on Oslo-Harlem, his voice a rich mixture of French accentuation and a booming African tenor. “Gla is the music, Gla is the fine art, Gla is the everything” and the artist focuses all these elements through the aesthetic of the African mask. Visually, the results are striking works of immense proportions with concepts that go deeper and deeper with each idea revealing the next in conceptually dense works of art with the mask as foreground. “There’s always something” says Andrew of his father’s work, work that’s consumed “45 years” of the artist’s life, which Andrew feels he has barely scratched the surface of.

Like Mr. Sompohi’s work that finds this parallel between western society and the African mask, Baya’s music draws parallels between various aspects of music and of course the theme of the mask through Oslo-Harlem. “I’m excited for this record to have this face” says Andrew of this visual element to the album. It will also be a theme running through the live shows I learn, as Andrew collaborated with his father and Red Bull to create masks that will form the backdrop to the stage, an experience Andrew quite “inspiring”. “It was like going to art school for a week.”

Like Mr. Sompohi’s work that finds this parallel between western society and the African mask, Baya’s music draws parallels between various aspects of music and of course the theme of the mask through Oslo-Harlem. “I’m excited for this record to have this face” says Andrew of this visual element to the album. It will also be a theme running through the live shows I learn, as Andrew collaborated with his father and Red Bull to create masks that will form the backdrop to the stage, an experience Andrew quite “inspiring”. “It was like going to art school for a week.”

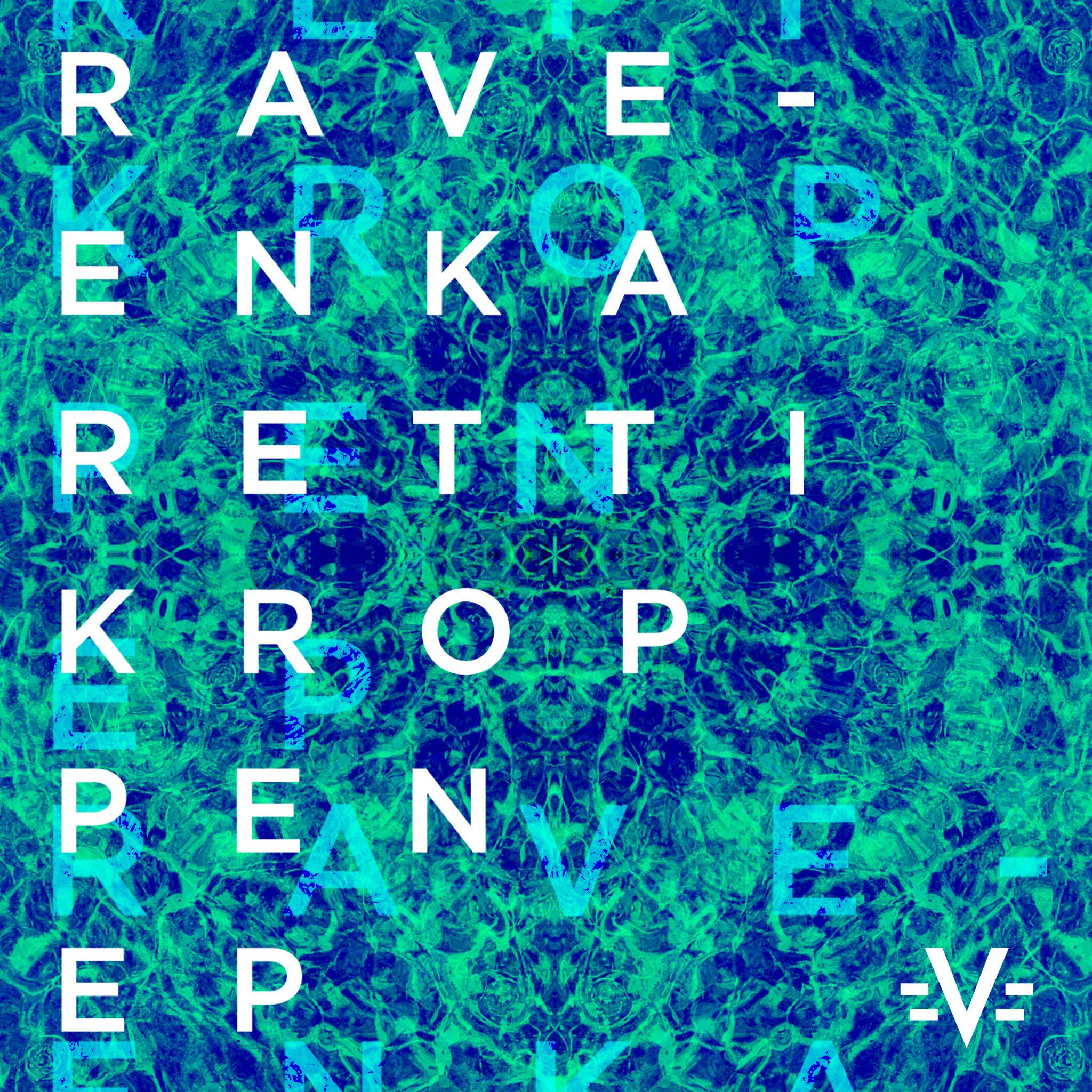

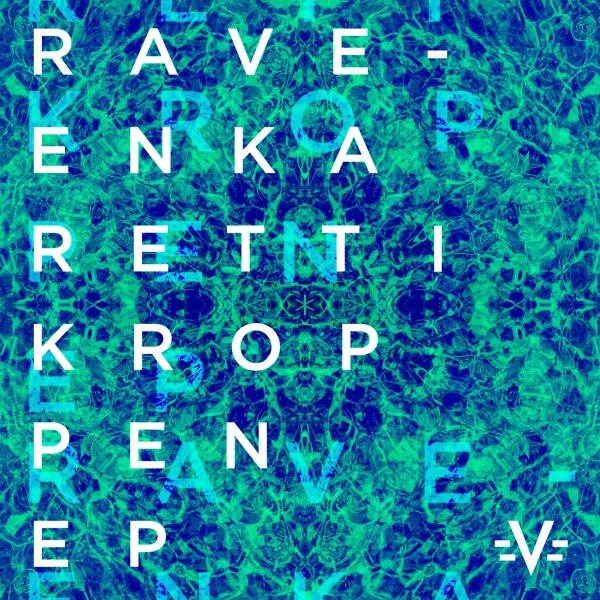

Rave-Enka (Ravi Burnsvik from the Fantastiske To) is on the cusp of releasing his sophomore effort on Paper Recordings, following 2015’s Påfulgen. It continues the machine aesthetic set forth on that release where musical sensibilities are transposed to the machine aesthetic, bridging the gap between genres to find Rave-Enka’s instinctive talent behind the tracks. It sees Rave-Enka go from strength to strength through three tracks with a polished production hand and an effervescent energy. In the following article we go track by track with Ravi while you listen to Rett-i-Kroppen in this exclusive stream.

Rave-Enka (Ravi Burnsvik from the Fantastiske To) is on the cusp of releasing his sophomore effort on Paper Recordings, following 2015’s Påfulgen. It continues the machine aesthetic set forth on that release where musical sensibilities are transposed to the machine aesthetic, bridging the gap between genres to find Rave-Enka’s instinctive talent behind the tracks. It sees Rave-Enka go from strength to strength through three tracks with a polished production hand and an effervescent energy. In the following article we go track by track with Ravi while you listen to Rett-i-Kroppen in this exclusive stream.