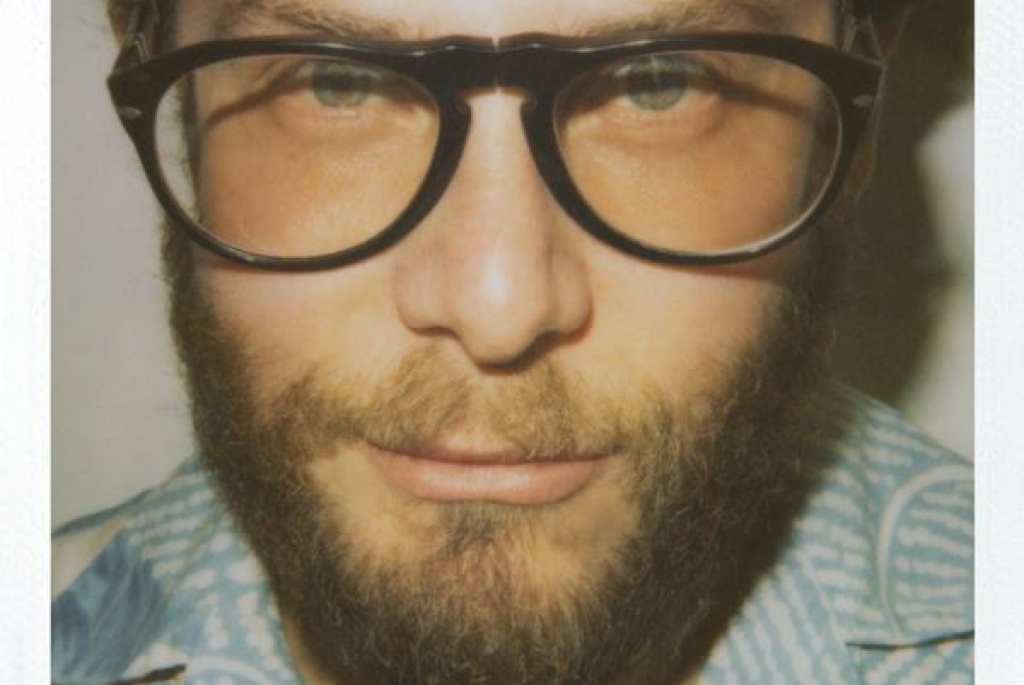

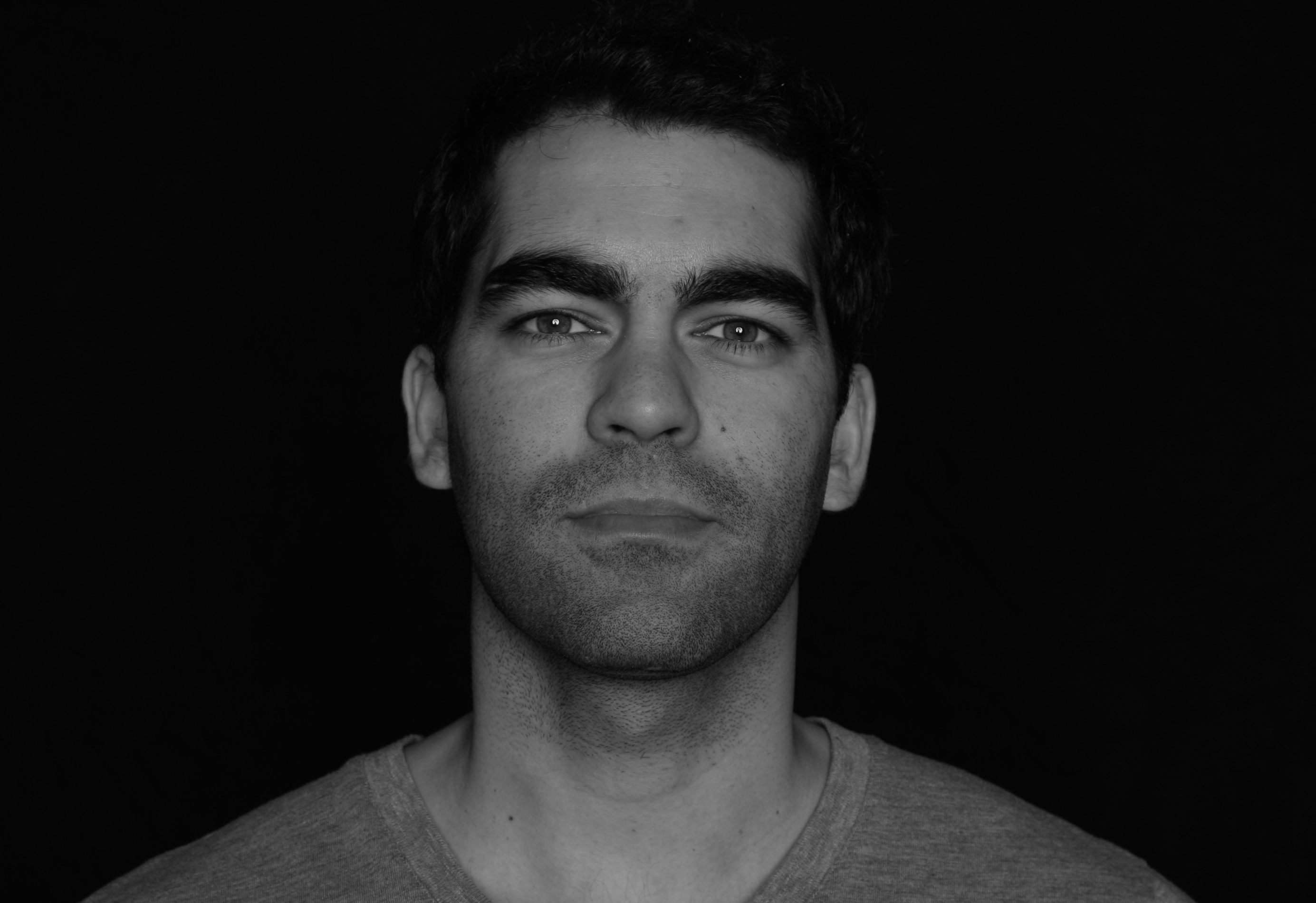

I didn’t want to talk about the pandemic. For something that consumed two years of our lives and continues to take its toll, most of us – and I’m sure George FitzGerald included – want to put it behind us. Its gravitational pull remains strong however and every conversation with artists and DJs I’ve had lately seems to skirt the event horizon of this cultural blackhole. Inevitably, our conversation too, falls headfirst into the subject and it’s the context of FitzGerald’s latest LP, Stellar Drifting. “It’s not a pandemic album, by any means,” insists FitzGerald, “but it’s impossible to separate that time from the music, because how could it not.”

“At the beginning of the pandemic, A lot of people thought, ‘cool I’m gonna write my masterpiece now’ and then it went on for so long.” Stellar Drifting is not that type of album and the artist wouldn’t pander to these illusions. Like most, he “found sitting alone in a room on his own,” during the pandemic “isn’t that conducive to writing music. You kind of need the stimulus of going out and meeting people and having new life experiences.” He found “watching Tiger king and making sourdough bread, before hitting the studio” didn’t have quite the same inspirational effect so while much of Stellar Drifting was finished during the pandemic, it doesn’t tap into the solemn and introspective concepts that mark those now-stereotypical “pandemic” albums.

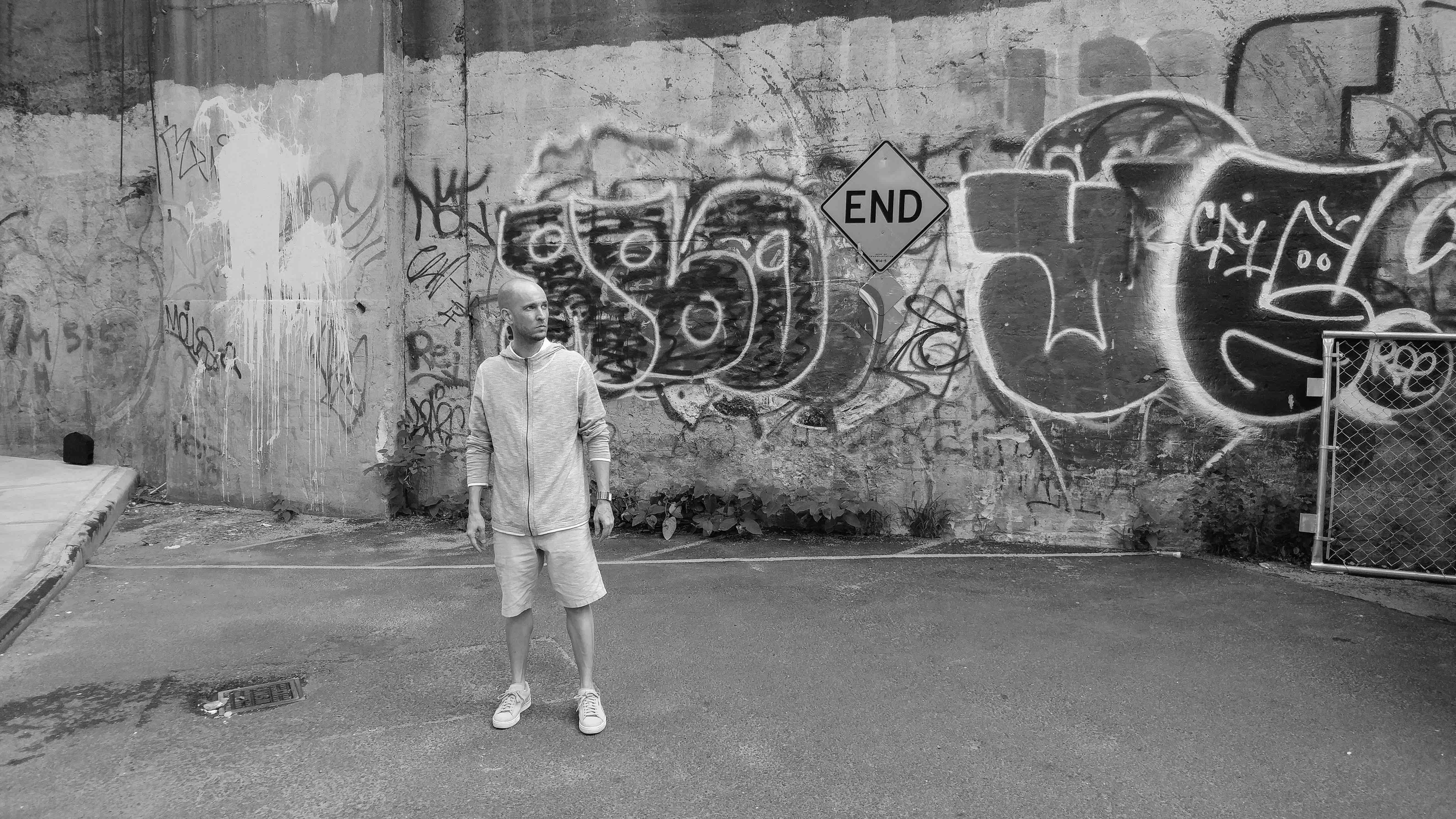

Back in 2018, before the pandemic, George FitzGerald was cementing a new phase in his career as an album artist with his determined sophomore record, All that must be, blazing a trail ahead from his dance floor roots. He was touring the album with a live band, playing as far afield as Morocco and the USA on the back of the record and the remix album that followed. Clash magazine, for one, called All that Must be “a simply gorgeous listen, one that displays a striking producer operating in full confidence,” at the time, with that confidence establishing George FitzGerald as an album artist.

Stellar Drifting however is no carbon copy of his last record. Instead, it marks another evolutionary notch in his sonic approach to the album. “It’s subtly different” from his last, he confirms, but it’s hard to pinpoint from the listener’s perspective. The expansive melodic and harmonic textures, gathering around stoic club-inspired rhythms remain central to his work, with the artist claiming that the whole album is “a little more major key, a bit more positive” than the last. “I wanted a broader palette harmonically than I have done in the past” and that also meant changing his approach to the creative process. “I went down a rabbit hole thinking how does my art matter in this world – what place does largely instrumental dance music have in a world where so much is going wrong?”

Relying on the tried and tested tactics from the “old friends” that constituted the familiar synthesisers and drum machines in the studio, wouldn’t suffice for this new creative pursuit. Instead FitzGerald turned his focus to “trying to build sound in different ways.” … And for that he looked to the stars for answers.

“Building synthesiser oscillators from photos (from Nasa space probes)” George FitzGerald found new textures, but more importantly new ways to “give the sound some meaning.” He asked himself: “What would it sound like if you took this photo of a nebula from the Hubble telescope and loaded it into Ableton?” And while the listener might still only hear what sounds like a synthesised pad or a bassline, FitzGerald revels in the fact that “50% of that is made of something like a nebula or Jupiter.”

Listening to Cold, the second single from the LP, there’s a warmth there that usurps its title and the origins of the album’s theme. Deep bass-lines swell, alluding to George’s dance floor roots, while melodies enchant, pulling the listener through starry atmospheres. It’s music that sits in that elusive realm of electronic music between a set of headphones and a club dance floor, where George FitzGerald occupies a space amongst other boundary-defying luminaries, like Caribou and Bonobo. There’s a moment on Cold however when everything seems to slow down, and a chopped vocal sample emerges in the stark mix during one the song’s quieter moments. It’s instantly familiar as Geroge FitzGerald, and in the wave of the deep bass that surrounds it, I’m suddenly transported back to 2012, when I first encountered the artist’s music and his breakout record, Child.

Hea had already cut his chops with six singles and EPs to date for labels like Hotflush and AUS before Child seemed to propel him to a whole new level. It seemed impossible to escape the magnitude of the record at that time, especially in the UK. It was being played in bars and clubs all over London, long before it was released. “That track changed a lot of stuff for me,” reminisces FitzGerald. “I have good memories of it.” It’s a track that still holds its own today. The chopped vocal, the keys, and the warm bass simply seems to roll through you, energising an ephemeral spirit in the pit of your stomach.

Child came at a time of great experimentation in the UK’s club music scene. In the post-Dubstep landscape, artists and DJs like Ben UFO, Joy O, Blawan, Midland and George FitzGerald were advancing to new territories in electronic club music, with Dubstep’s deep and tumultuous bass, and experimental attitudes informing new styles of House, UK Garage, Techno and Electro coming out of the region. Later these artists and DJs would all go “off into slightly different directions,” with more focussed pursuits towards traditional genres and styles, but for a moment the UK was buzzing with a creative air in the context of club music, and George FitzGerald was a part of it. He produced Child as a “deep house track made off the cuff,” while holding court over the Deep House section of a record store he worked, but it impressed on the scene and the DJ circuit a different approach to Deep House, one a fair few attempted to mimic.

“That was fun for a bit,” reminisces FitzGerald, “but honestly that’s not what I wanted starting off.” As the other artists from the post-dubstep scene grew and moved into different directions, so did he. “I stopped writing music for club sets a long time ago.” Never really one to write “four tunes in a day,” he was always looking for something more substantial in his music, and for him the album format had always seemed like this intangible purpose of his pursuits, perhaps even planting that initial seed to the questions,” how does my art matter in this world.”

“I always wanted to see if I could do it”, he says about the idea that spurned on his first album, Fading Love. “When I started, the thought of writing a ten track album on my own, it just seemed insane,” but it turned out to be something he instinctively mastered. Fading Love was an immediate success. The Guardian called it “an intimate and beautifully textured record” and it went some way in establishing a nascent crossover success. The benchmark he’d set himself it seemed had been achieved. “I really enjoyed the process,” and the confidence set him on a path, leading up to today and his latest album, Stellar Drifting.

In his continuous evolution through these records as an artist, George FitzGerald has emerged as a more-than-capable song-writer, on par with his technical skill as a producer. Over the last couple of records, the cut up vocals have matured into fully rounded pop songs with guest vocal appearances, from the likes of Tracey Thorne on All that Must Be and Panda Bear on Stellar Drifting validating FitzGerald’s song-writing skills. “I wanted to scratch the itch of writing songs,” he says. It’s an itch that has been with him since adolescence, listening to the likes of Gary Numan and Billy Corgan of Smashing Pumpkins.

“A lot of people have asked me about the Billy Corgan influence,” he says with a laugh when I pry. “The funny thing is that when you’re fifteen for six months you’re a Garage kid, and then suddenly you’re like ‘I’m just gonna start dressing differently and go watch the Smashing Pumpkins” when youthful “tribal” instincts kick in. “The thing with Billy Corgan is he’s obviously an amazing song-writer, but there’s also this other gothic side to him. There’s this kind of grandeur to the best Smashing Pumpkins stuff and I’ve always loved that.“ FitzGerald suggests you can hear those “maximalists” elements in his first single from the new album, Ultraviolet with its cascading arrangements and bold orchestration.

It’s certainly the furthest, I’ve heard George FitzGerald travel from his dance -floor roots, and I’m curious how he would channel a track like that into a DJ set, and the answer is unsurprisingly, he wouldn’t. “I find it quite difficult,” he says about making his album pieces work in his sets. On the rare occasion he might try to accommodate a request, he’s all too aware of the “rules in clubs” and the “ways of directing energy” through a set. He started out as a DJ after all, and while he might not consider it a central node to his artistic identity today, it’s still very much there and it makes for a welcomed change to his live sets. “Djing is just a really nice counterpoint. It’s very spontaneous and a lot less heavy than a live show.”

Most significantly it’s a way of maintaining that connection to club music and the dance floor. “Writing albums doesn’t reconnect you with audiences and clubbing, and what got you into the music in the first place, like DJing.” It’s something that he was particularly aware of during the pandemic. “What I missed; travelling around and meeting new people and going to new places, was a really important part of how I write my music, I didn’t know that before.” He hadn’t been gigging much during the pandemic and after, as he was finishing off the album, and before that he’d mainly been focussed on his live sets. Through DJing, in part, he’s looking to “get that connection back with a scene.”

“Weirdly” he says, he’s “quite desperate to release an EP” too, going full circle back to his roots after a trio of albums. Stellar Drifting will arrive four years after his last, “and that in modern music is an age,” FitzGerald muses. Not that long ago it would’ve been considered a come-back record, but for an artist like George FitzGerald who is “always evolving as an artist,” it’s another evolutionary step. “So much has happened since the last record and the world is completely different,” and it’s only natural for these elements to feed into the growth of the artist. Whether he’ll eventually receive an answer to his question: “does my art matter in this world?” after the release of the album, remains to be seen, but one thing is certain; it would certainly matter in the context of George FitzGerald’s artistic legacy.

Tell me about going to the Loft.

Tell me about going to the Loft. Did he just play on Blå’s soundsystem?

Did he just play on Blå’s soundsystem? Did you ever talk to him about the peak era of the Loft?

Did you ever talk to him about the peak era of the Loft?

“Drugs, nothing more,” says Tornike, but “when they raided the club, no-one was arrested for dealing drugs and they couldn’t find any drug dealers inside the club, only finding 2 or 3 grams” on individuals. The club owners were arrested too, without a warrant on some overblown claims of obstruction, which never resulted in any charges brought forward, but what happened directly after the raid, was a force of solidarity in a clubbing community that we haven’t seen since the time of the criminal justice and public order act. People like Tornike, who had started gathering outside Bassiani as the police were carting off their friends and colleagues, were protesting the arrests. “We were trying to figure out what was happening,” explains Tornike who “didn’t even know which Police station they took them to” at the time.

“Drugs, nothing more,” says Tornike, but “when they raided the club, no-one was arrested for dealing drugs and they couldn’t find any drug dealers inside the club, only finding 2 or 3 grams” on individuals. The club owners were arrested too, without a warrant on some overblown claims of obstruction, which never resulted in any charges brought forward, but what happened directly after the raid, was a force of solidarity in a clubbing community that we haven’t seen since the time of the criminal justice and public order act. People like Tornike, who had started gathering outside Bassiani as the police were carting off their friends and colleagues, were protesting the arrests. “We were trying to figure out what was happening,” explains Tornike who “didn’t even know which Police station they took them to” at the time.

Working with TB Arthur and people like BMG, do you think It’s changed the way you make music?

Working with TB Arthur and people like BMG, do you think It’s changed the way you make music? Like every DJ out there today you have an agent that takes care of your bookings, but do you have the final say where you’ll play?

Like every DJ out there today you have an agent that takes care of your bookings, but do you have the final say where you’ll play?

The idea of dugnadsånden is also how Ra-Shidi had her start as a DJ. “I just went up to the manager at Circa and asked if I could play there, and he just said, ‘yeah sure’.” Unfortunately, Circa is coming to an end in two months, and Ra-Shidi is hoping Storgata Camping will carry the beacon for the clubbing community, with more reserved bookings but with a bigger impact to attract the larger audience to fill the dance floor.

The idea of dugnadsånden is also how Ra-Shidi had her start as a DJ. “I just went up to the manager at Circa and asked if I could play there, and he just said, ‘yeah sure’.” Unfortunately, Circa is coming to an end in two months, and Ra-Shidi is hoping Storgata Camping will carry the beacon for the clubbing community, with more reserved bookings but with a bigger impact to attract the larger audience to fill the dance floor.

The way you explained it was that the shop, Afro Synth is very much a labour of love for you. Can you tell me a bit more about what inspired you to start and run the shop?

The way you explained it was that the shop, Afro Synth is very much a labour of love for you. Can you tell me a bit more about what inspired you to start and run the shop?

The origins of Techno

The origins of Techno

Mikrometeorittene’s closest descendant is Mechanized World, but offering a much more contemporary approach to the Techno genre. I wonder if it is down to an evolution in their work, but Truls suggests not. “I feel in a way we go in a circle” and redefining the parameters between the projects has allowed them more freedom to explore these more purest forms of their cavernous electronic music interests. KSMISK is a “different vibe in general” according to Robin who also believes they should’ve separated these different sounds “years ago”.

Mikrometeorittene’s closest descendant is Mechanized World, but offering a much more contemporary approach to the Techno genre. I wonder if it is down to an evolution in their work, but Truls suggests not. “I feel in a way we go in a circle” and redefining the parameters between the projects has allowed them more freedom to explore these more purest forms of their cavernous electronic music interests. KSMISK is a “different vibe in general” according to Robin who also believes they should’ve separated these different sounds “years ago”.

Fredrik didn’t go straight from metal to Techno however, but drumming played an integral role in th DJ prowess he displayed early on. Fredrik’s acute ear for rhythm took to DJing very naturally and as a tram goes by in the background by way of serendipitous illumination, Fredrik explains; “I can hear the tram go by and I can immediately feel the rhythm.” He “always knew what DJing was about” because of his older brothers and when he turned 18 and “started partying” DJing came from Fredrik’s desire “to perform music”. He bought “some cheap decks” and through a period of “listening to commercial, shit music” started DJing.

Fredrik didn’t go straight from metal to Techno however, but drumming played an integral role in th DJ prowess he displayed early on. Fredrik’s acute ear for rhythm took to DJing very naturally and as a tram goes by in the background by way of serendipitous illumination, Fredrik explains; “I can hear the tram go by and I can immediately feel the rhythm.” He “always knew what DJing was about” because of his older brothers and when he turned 18 and “started partying” DJing came from Fredrik’s desire “to perform music”. He bought “some cheap decks” and through a period of “listening to commercial, shit music” started DJing.

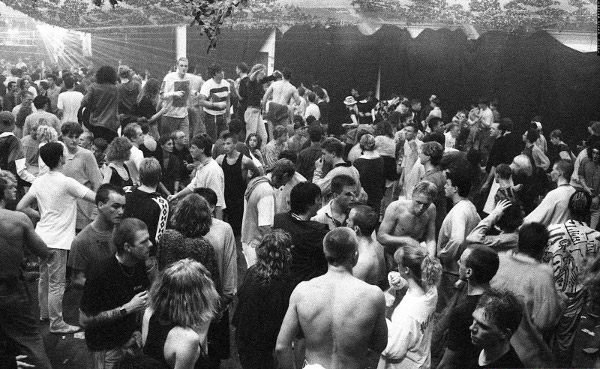

Later that evening after our interview the energy is electric in Jæger’s backyard, peaking at excessive levels, and then suddenly a drop in the bottom end. A wispy melody of some unknown origins builds tension and the whole crowd lurches forward, towards the booth as one. There’s a moment of inextricable pause… it’s nearly silent… and then an exhilarated whoop from the audience as the bass and drums kick back in to the pulse of the dance floor.

Later that evening after our interview the energy is electric in Jæger’s backyard, peaking at excessive levels, and then suddenly a drop in the bottom end. A wispy melody of some unknown origins builds tension and the whole crowd lurches forward, towards the booth as one. There’s a moment of inextricable pause… it’s nearly silent… and then an exhilarated whoop from the audience as the bass and drums kick back in to the pulse of the dance floor.

It seems however that opinion is divided between a high profile DJ like Thaemlitz and the DJs that still work at a local, subcultural level. While a DJ like Thaemlitz is openly opposed to mixed spaces as it heteronormalises the queer aspects of the culture, a younger generation of DJs like Terje Dybdahl and Timothy Wang are embracing and indeed welcoming the mixed orientation of the audiences. As more previously rigidly queer spaces and events like Kaos, overwhelmingly welcome mixed audiences, albeit retaining their queer identity, it appears that a mixed philosophy is becoming the acceptable norm. My first thought was that this might be predicated on a regional aspect since in Europe and the UK this music and its culture was first adopted by a heterosexual audience, but this doesn’t really concur with what US DJ Jason Kendig from Honey Soundsystem told me last year during an interview for Jæger’s blog. He put emphasis on the fact that he and the soundsystem’s “first experiences in dance music were not necessarily in queer spaces”.

It seems however that opinion is divided between a high profile DJ like Thaemlitz and the DJs that still work at a local, subcultural level. While a DJ like Thaemlitz is openly opposed to mixed spaces as it heteronormalises the queer aspects of the culture, a younger generation of DJs like Terje Dybdahl and Timothy Wang are embracing and indeed welcoming the mixed orientation of the audiences. As more previously rigidly queer spaces and events like Kaos, overwhelmingly welcome mixed audiences, albeit retaining their queer identity, it appears that a mixed philosophy is becoming the acceptable norm. My first thought was that this might be predicated on a regional aspect since in Europe and the UK this music and its culture was first adopted by a heterosexual audience, but this doesn’t really concur with what US DJ Jason Kendig from Honey Soundsystem told me last year during an interview for Jæger’s blog. He put emphasis on the fact that he and the soundsystem’s “first experiences in dance music were not necessarily in queer spaces”.

Behind every good DJ is that urge to dig deeper and further, and in Christopher it manifested into an obsessive-compulsive habit when a couple of Joey Negro compilations came his way. “A lot of the House music I listened to came from these tracks” explains Christopher and what started in House music moved into Disco, Soul and Boogie’s more obscure corners. “When I hear a sample that I know from somewhere I get totally obsessed about finding it“, says Christopher. The DJ turned collector after a digging session in Berlin. Stumbling on the originals of some of his “favourite” House tracks, Christopher started exploring the outlying regions of Disco through his sets. “Felix (Klein) did exactly the same thing at the same time” and the two DJs “hooked up and started playing Soul, Disco and Boogie together.” Driven by his desire to find the original of a sample from a House track, and looking beyond the obvious, Christopher “started spending all (his) money on records” and Disco lead to Boogie and of course eventually Boogienetter… but first there was Diskotaket.

Behind every good DJ is that urge to dig deeper and further, and in Christopher it manifested into an obsessive-compulsive habit when a couple of Joey Negro compilations came his way. “A lot of the House music I listened to came from these tracks” explains Christopher and what started in House music moved into Disco, Soul and Boogie’s more obscure corners. “When I hear a sample that I know from somewhere I get totally obsessed about finding it“, says Christopher. The DJ turned collector after a digging session in Berlin. Stumbling on the originals of some of his “favourite” House tracks, Christopher started exploring the outlying regions of Disco through his sets. “Felix (Klein) did exactly the same thing at the same time” and the two DJs “hooked up and started playing Soul, Disco and Boogie together.” Driven by his desire to find the original of a sample from a House track, and looking beyond the obvious, Christopher “started spending all (his) money on records” and Disco lead to Boogie and of course eventually Boogienetter… but first there was Diskotaket.

I was raised in the US, and immigrated to Japan – both of which are cultures with nearly zero federal funding for art and music. So while I understand the logic of feeling entitled to a share of public funds created by one’s tax payments, I also am never surprised when those funds go to the most conservative cultural elements – like classical music halls, or galleries for housing old paintings. Similarly, I never forget futurism’s role as the official art of fascist Italy, or social realism’s role in totalitarian Chinese and Soviet regimes, etc. So both my sense of history and personal experience keeps me from ever being excited by news of countries that fund artists.

I was raised in the US, and immigrated to Japan – both of which are cultures with nearly zero federal funding for art and music. So while I understand the logic of feeling entitled to a share of public funds created by one’s tax payments, I also am never surprised when those funds go to the most conservative cultural elements – like classical music halls, or galleries for housing old paintings. Similarly, I never forget futurism’s role as the official art of fascist Italy, or social realism’s role in totalitarian Chinese and Soviet regimes, etc. So both my sense of history and personal experience keeps me from ever being excited by news of countries that fund artists.

Quarantine made an instant impression on the listener and whether you liked it or loathed it, it was definitely not inadmissible. Critics merely praised it, and accolades for Laurel Halo’s work came in abundance, but public opinion definitely remained divided. “The record’s not meant for everyone”, explained Halo in an interview with the Quietus shortly after the release. “(I)t’s not a pop record in the slightest so I think people expecting that would be disappointed by the vocal tone and production approach.” By the time you get to the second song on the album “Years” you would either be entranced or disenchanted by the beat-less sojourn through Halo’s emotive depths on her debut album. Although Halo’s debut EP, King Felix certainly had ears pricking up everywhere, it would be Quarantine that launched her career, making a vivid statement from the music right through to the artwork, designed by Makota Aira; a colourful and humorous display of Seppuku (ritual Japanese suicide).

Quarantine made an instant impression on the listener and whether you liked it or loathed it, it was definitely not inadmissible. Critics merely praised it, and accolades for Laurel Halo’s work came in abundance, but public opinion definitely remained divided. “The record’s not meant for everyone”, explained Halo in an interview with the Quietus shortly after the release. “(I)t’s not a pop record in the slightest so I think people expecting that would be disappointed by the vocal tone and production approach.” By the time you get to the second song on the album “Years” you would either be entranced or disenchanted by the beat-less sojourn through Halo’s emotive depths on her debut album. Although Halo’s debut EP, King Felix certainly had ears pricking up everywhere, it would be Quarantine that launched her career, making a vivid statement from the music right through to the artwork, designed by Makota Aira; a colourful and humorous display of Seppuku (ritual Japanese suicide).

That was around 2004/5 I guess?

That was around 2004/5 I guess? Roland TR- 909

Roland TR- 909 Oberheim Matrix 12

Oberheim Matrix 12 Roland TB-303

Roland TB-303 Universal Audio Apollo

Universal Audio Apollo A Korg Guy

A Korg Guy

It kind of just happened. I missed working with music, and that was one of the first things I did feel along the trip. I’ve always been heavily interested in making sound recordings. A lot of people that travel, they either blog it or take pictures, and I thought for me, it would be quite natural to make mix tapes of the music we were listening to a lot on the road, and mix it with experiences on the road.

It kind of just happened. I missed working with music, and that was one of the first things I did feel along the trip. I’ve always been heavily interested in making sound recordings. A lot of people that travel, they either blog it or take pictures, and I thought for me, it would be quite natural to make mix tapes of the music we were listening to a lot on the road, and mix it with experiences on the road.  Yes, I’m always collecting music, but it’s not in the way that you think. A lot of people have this romantic idea that I’m going to record stores every week and digging South American gems. First of all it’s not like that at all there, there are not that many record stores there apart from the big cities. I don’t have the space for it and I don’t have a record player on the road. I did consider getting a portable record player, but then I got scared, because half the time you just become a digger instead of travelling and all the other stuff that I enjoy. So I’m just collecting music online.

Yes, I’m always collecting music, but it’s not in the way that you think. A lot of people have this romantic idea that I’m going to record stores every week and digging South American gems. First of all it’s not like that at all there, there are not that many record stores there apart from the big cities. I don’t have the space for it and I don’t have a record player on the road. I did consider getting a portable record player, but then I got scared, because half the time you just become a digger instead of travelling and all the other stuff that I enjoy. So I’m just collecting music online.  You mentioned diversity there and I must admit hew first place I really picked up on an eclecticism in the booth becoming popular was at Trouw. Do you think that was a part of the legacy it left on the DJ scene?

You mentioned diversity there and I must admit hew first place I really picked up on an eclecticism in the booth becoming popular was at Trouw. Do you think that was a part of the legacy it left on the DJ scene?

T

T

There’s a lot of emphasis on a visual presentation. What do you hope the visual accompaniment brings to the releases away from the music?

There’s a lot of emphasis on a visual presentation. What do you hope the visual accompaniment brings to the releases away from the music?

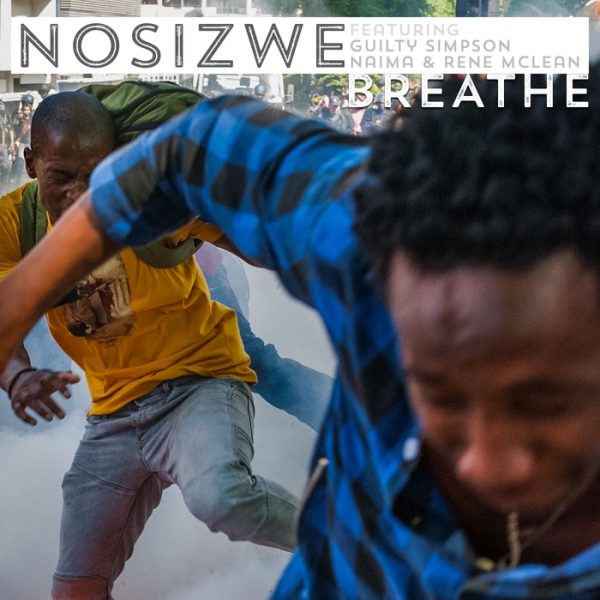

She’s vocal, yet fair on these issues and obviously very conscious of what’s going on in South Africa, and when I ask how much these issues inform her music she offers an example from “In Fragments”, the song Breathe, which she “wrote and dedicated to the student uprising.” The visual accompaniment to the single, a picture of two boys running away from a smoke grenade, which removed out of context looks like two younger men dancing, which Nosizwe brings back to the reality of the situation through her lyrics for Breathe. “I can’t breathe, I can’t see the sun for the light of day”, does not talk of a joyous occasion and after really studying the picture everything falls into its perspective. But as much as that song is about the student uprising, something that “deeply impacted” the artist, it also works in the context of American politics: “That song was definitely a reflection of the politics of SA, but also the United States with all the cop killings and the black lives matter movement.” Political issues are also moments of hope and encouragement for the artist, translated into acknowledgement and a deep seated respect in her music as inspired by the people of South Africa. “Hiya” from the album speaks of feminism and spirituality, not as a “pseudo philosophical” construct, but as a message of an openness that reflects an ingrained history between the people and the earth in South Africa and in the subtext it’s about empowerment. That “song was a thank you to my deeply spiritual and hippy sisterhood” explains Nosizwe. It is a “completely different access and entry to spirituality” for the singer and one that makes it “totally acceptable that you can acknowledge the ancestors on Saturday, go to church on Sunday and smoke weed on top of Devil’s peak on Sunday” with no contradiction between those spiritual elements, much like her album pieces together different, often contrasting things to make a whole.

She’s vocal, yet fair on these issues and obviously very conscious of what’s going on in South Africa, and when I ask how much these issues inform her music she offers an example from “In Fragments”, the song Breathe, which she “wrote and dedicated to the student uprising.” The visual accompaniment to the single, a picture of two boys running away from a smoke grenade, which removed out of context looks like two younger men dancing, which Nosizwe brings back to the reality of the situation through her lyrics for Breathe. “I can’t breathe, I can’t see the sun for the light of day”, does not talk of a joyous occasion and after really studying the picture everything falls into its perspective. But as much as that song is about the student uprising, something that “deeply impacted” the artist, it also works in the context of American politics: “That song was definitely a reflection of the politics of SA, but also the United States with all the cop killings and the black lives matter movement.” Political issues are also moments of hope and encouragement for the artist, translated into acknowledgement and a deep seated respect in her music as inspired by the people of South Africa. “Hiya” from the album speaks of feminism and spirituality, not as a “pseudo philosophical” construct, but as a message of an openness that reflects an ingrained history between the people and the earth in South Africa and in the subtext it’s about empowerment. That “song was a thank you to my deeply spiritual and hippy sisterhood” explains Nosizwe. It is a “completely different access and entry to spirituality” for the singer and one that makes it “totally acceptable that you can acknowledge the ancestors on Saturday, go to church on Sunday and smoke weed on top of Devil’s peak on Sunday” with no contradiction between those spiritual elements, much like her album pieces together different, often contrasting things to make a whole.

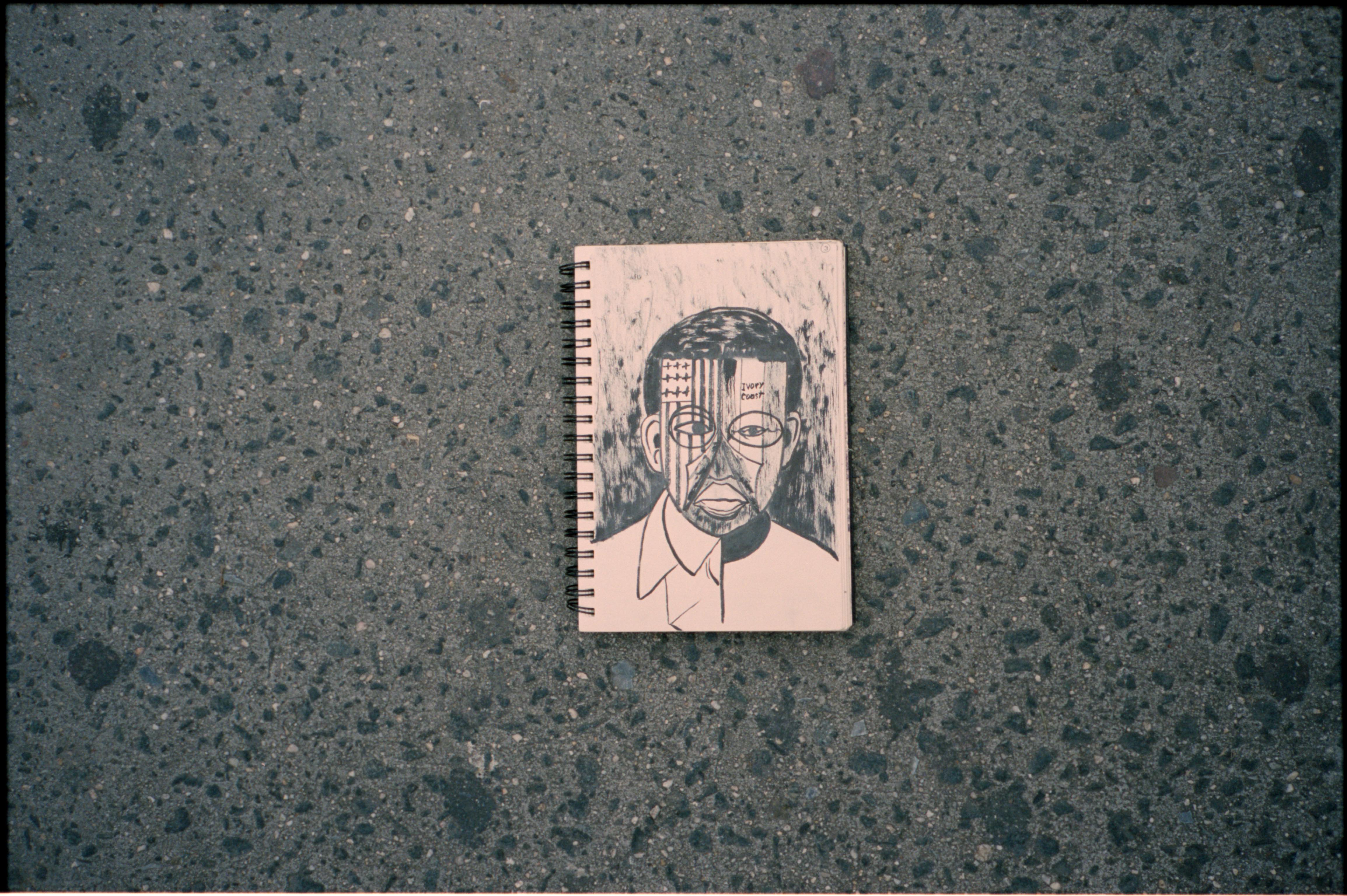

A talented young artist from the Ivory Coast, Mr. Sompohi found himself in Rome and then Bergen on scholarships to study sculpture in the eighties. It was in Norway where he would have the significant encounter with Caroline Baardsen that brought Andrew into the world, but it’s also here where he expounded on his lifelong work; delving into the concepts of the African mask through a thoroughly western image.“He found the African mask at Sagene kirke”, explains Andrew, “where he saw the mask in the church door, and he saw the parallel between the African mask and western society.” He calls the concept Gla, shortened from Glalogy. “Gla is the manifestation of the African spirit tradition, African society”, explains Mr. Sompohi during an interlude on Oslo-Harlem, his voice a rich mixture of French accentuation and a booming African tenor. “Gla is the music, Gla is the fine art, Gla is the everything” and the artist focuses all these elements through the aesthetic of the African mask. Visually, the results are striking works of immense proportions with concepts that go deeper and deeper with each idea revealing the next in conceptually dense works of art with the mask as foreground. “There’s always something” says Andrew of his father’s work, work that’s consumed “45 years” of the artist’s life, which Andrew feels he has barely scratched the surface of.

A talented young artist from the Ivory Coast, Mr. Sompohi found himself in Rome and then Bergen on scholarships to study sculpture in the eighties. It was in Norway where he would have the significant encounter with Caroline Baardsen that brought Andrew into the world, but it’s also here where he expounded on his lifelong work; delving into the concepts of the African mask through a thoroughly western image.“He found the African mask at Sagene kirke”, explains Andrew, “where he saw the mask in the church door, and he saw the parallel between the African mask and western society.” He calls the concept Gla, shortened from Glalogy. “Gla is the manifestation of the African spirit tradition, African society”, explains Mr. Sompohi during an interlude on Oslo-Harlem, his voice a rich mixture of French accentuation and a booming African tenor. “Gla is the music, Gla is the fine art, Gla is the everything” and the artist focuses all these elements through the aesthetic of the African mask. Visually, the results are striking works of immense proportions with concepts that go deeper and deeper with each idea revealing the next in conceptually dense works of art with the mask as foreground. “There’s always something” says Andrew of his father’s work, work that’s consumed “45 years” of the artist’s life, which Andrew feels he has barely scratched the surface of.

Like Mr. Sompohi’s work that finds this parallel between western society and the African mask, Baya’s music draws parallels between various aspects of music and of course the theme of the mask through Oslo-Harlem. “I’m excited for this record to have this face” says Andrew of this visual element to the album. It will also be a theme running through the live shows I learn, as Andrew collaborated with his father and Red Bull to create masks that will form the backdrop to the stage, an experience Andrew quite “inspiring”. “It was like going to art school for a week.”

Like Mr. Sompohi’s work that finds this parallel between western society and the African mask, Baya’s music draws parallels between various aspects of music and of course the theme of the mask through Oslo-Harlem. “I’m excited for this record to have this face” says Andrew of this visual element to the album. It will also be a theme running through the live shows I learn, as Andrew collaborated with his father and Red Bull to create masks that will form the backdrop to the stage, an experience Andrew quite “inspiring”. “It was like going to art school for a week.”

Rave-Enka (Ravi Burnsvik from the Fantastiske To) is on the cusp of releasing his sophomore effort on Paper Recordings, following 2015’s Påfulgen. It continues the machine aesthetic set forth on that release where musical sensibilities are transposed to the machine aesthetic, bridging the gap between genres to find Rave-Enka’s instinctive talent behind the tracks. It sees Rave-Enka go from strength to strength through three tracks with a polished production hand and an effervescent energy. In the following article we go track by track with Ravi while you listen to Rett-i-Kroppen in this exclusive stream.

Rave-Enka (Ravi Burnsvik from the Fantastiske To) is on the cusp of releasing his sophomore effort on Paper Recordings, following 2015’s Påfulgen. It continues the machine aesthetic set forth on that release where musical sensibilities are transposed to the machine aesthetic, bridging the gap between genres to find Rave-Enka’s instinctive talent behind the tracks. It sees Rave-Enka go from strength to strength through three tracks with a polished production hand and an effervescent energy. In the following article we go track by track with Ravi while you listen to Rett-i-Kroppen in this exclusive stream.