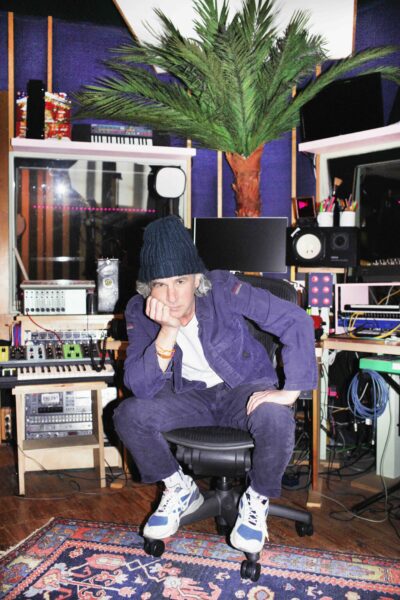

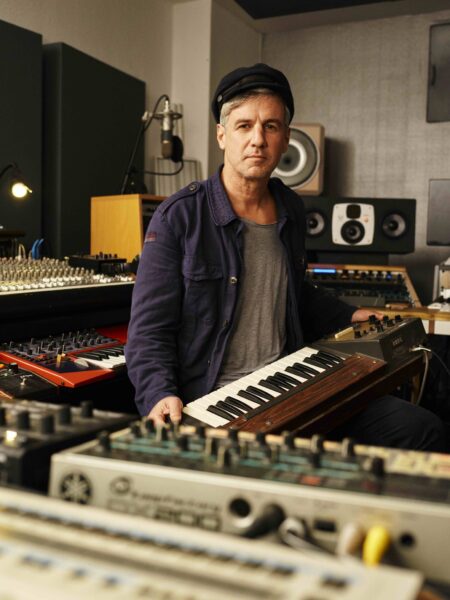

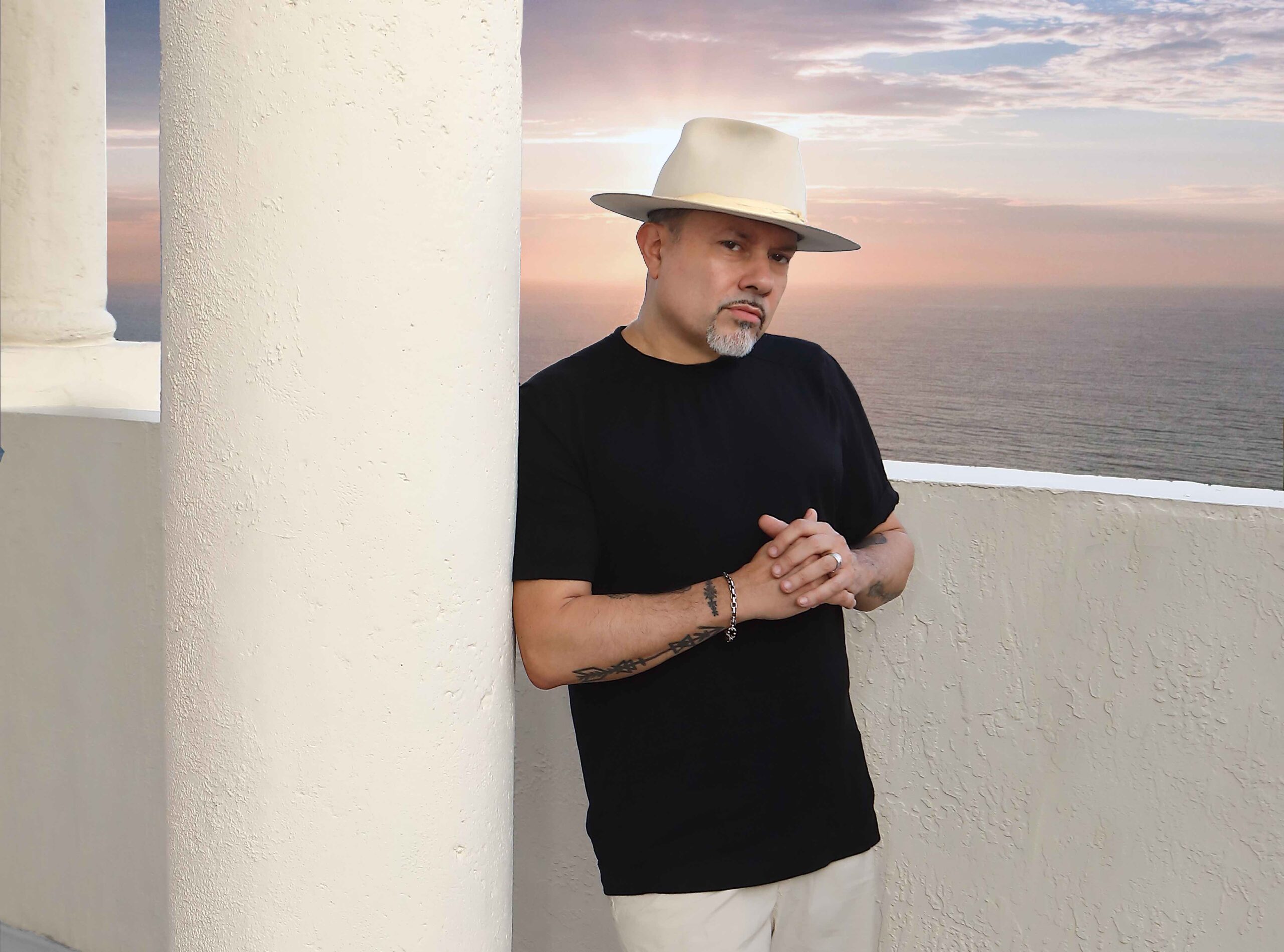

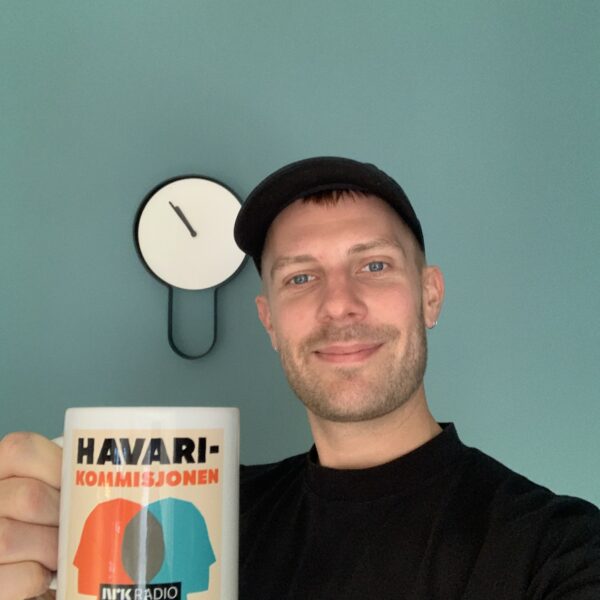

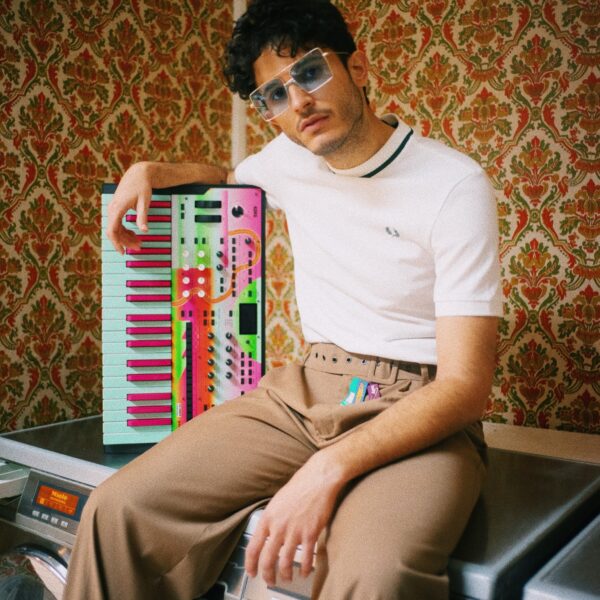

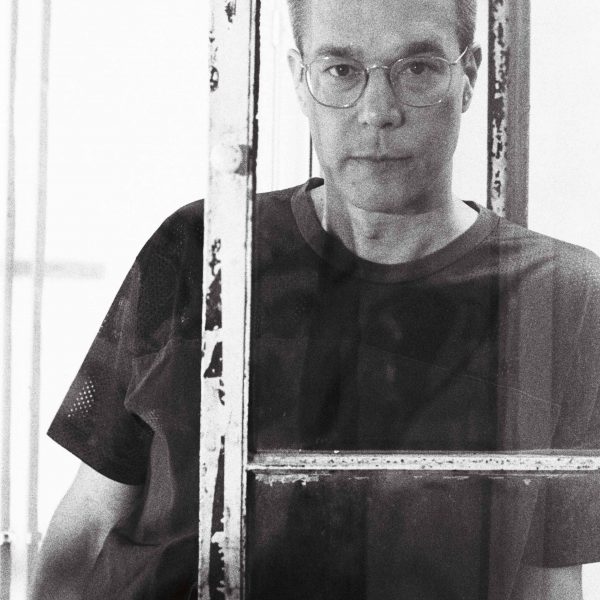

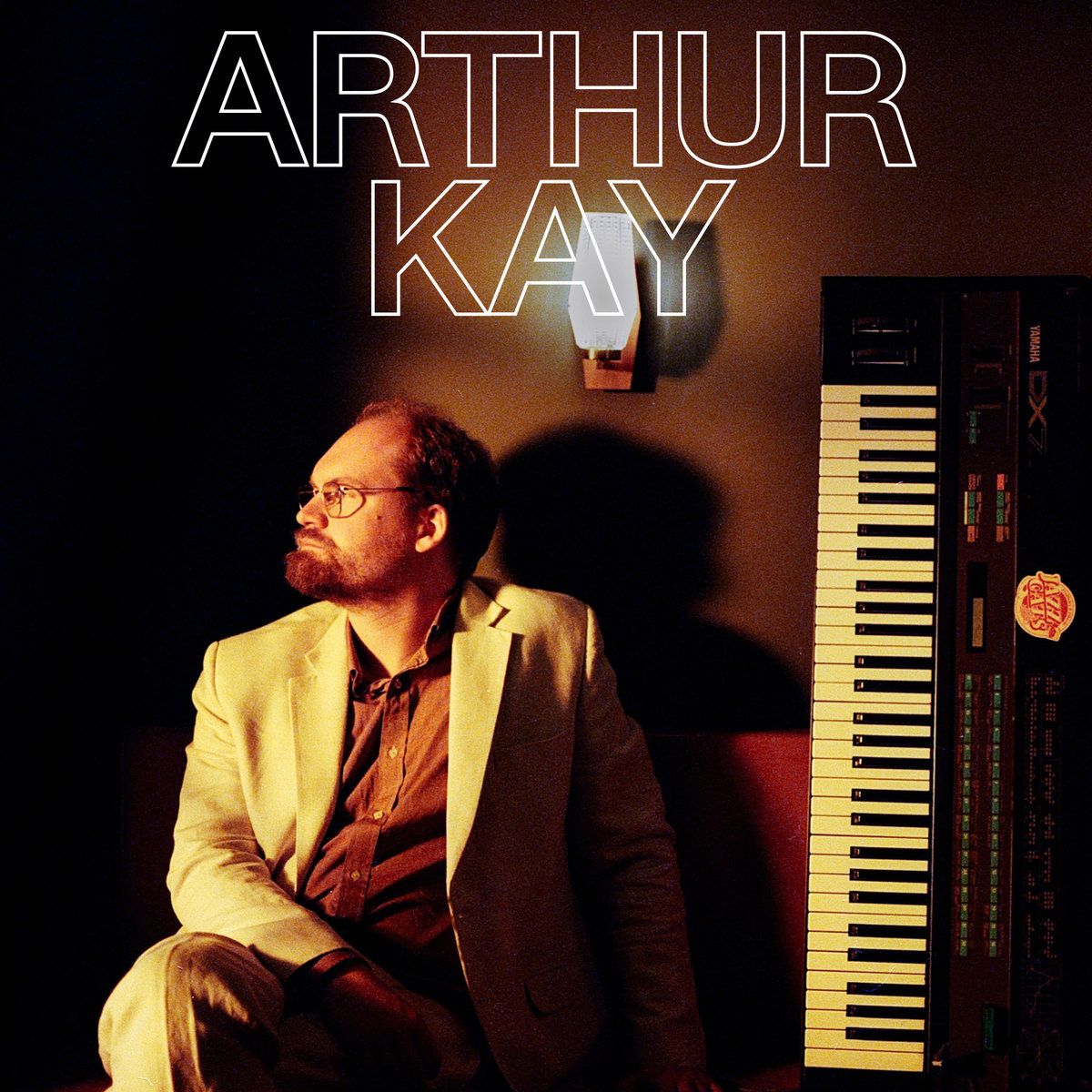

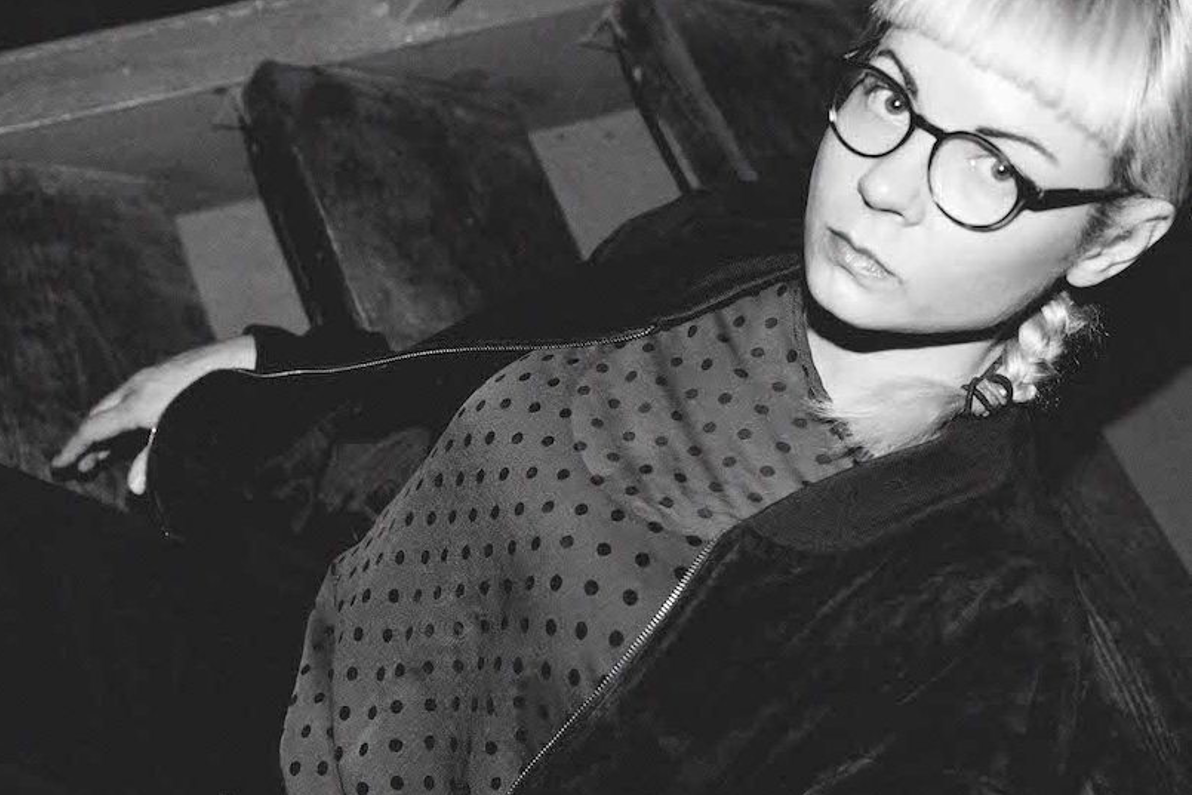

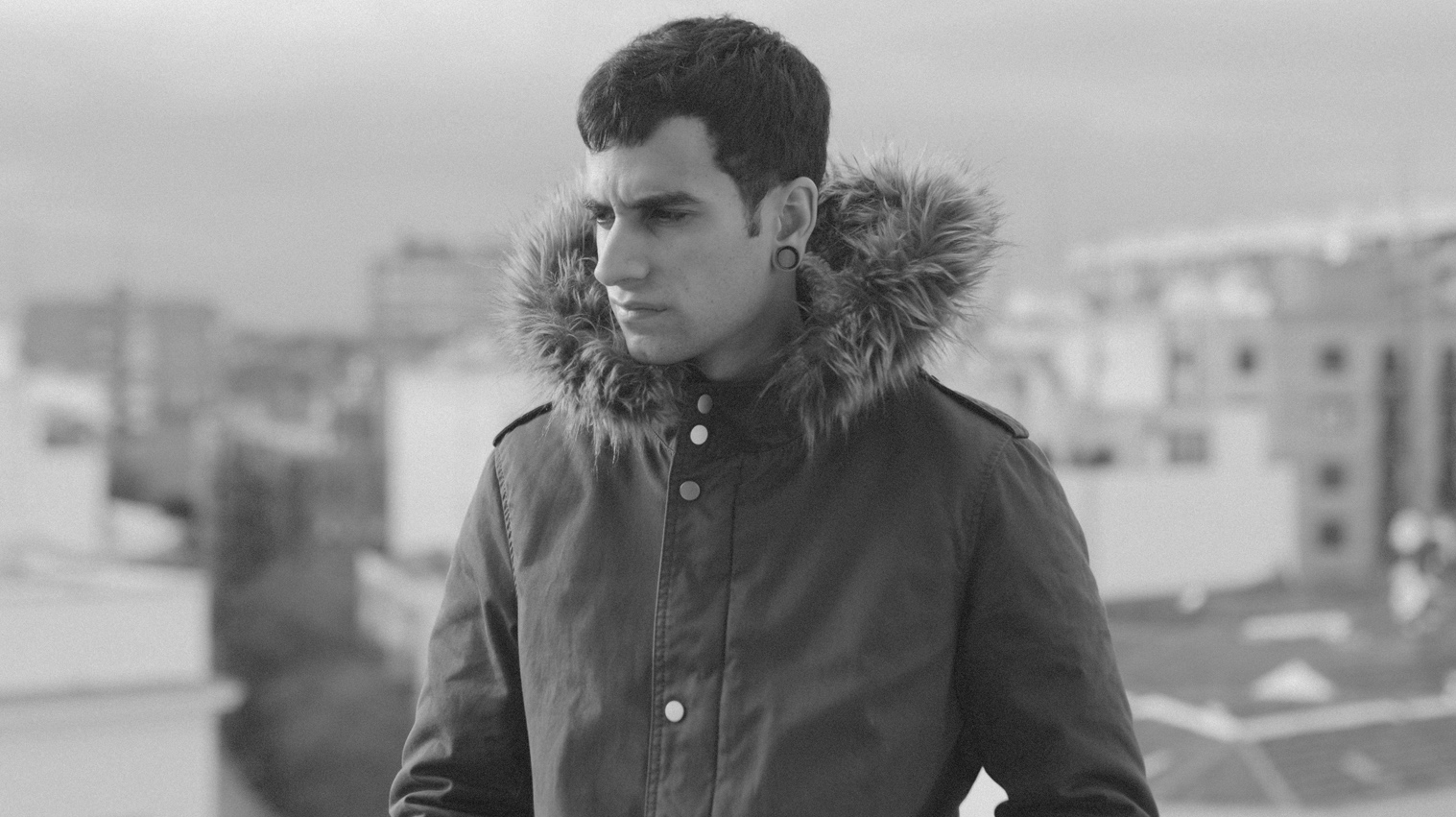

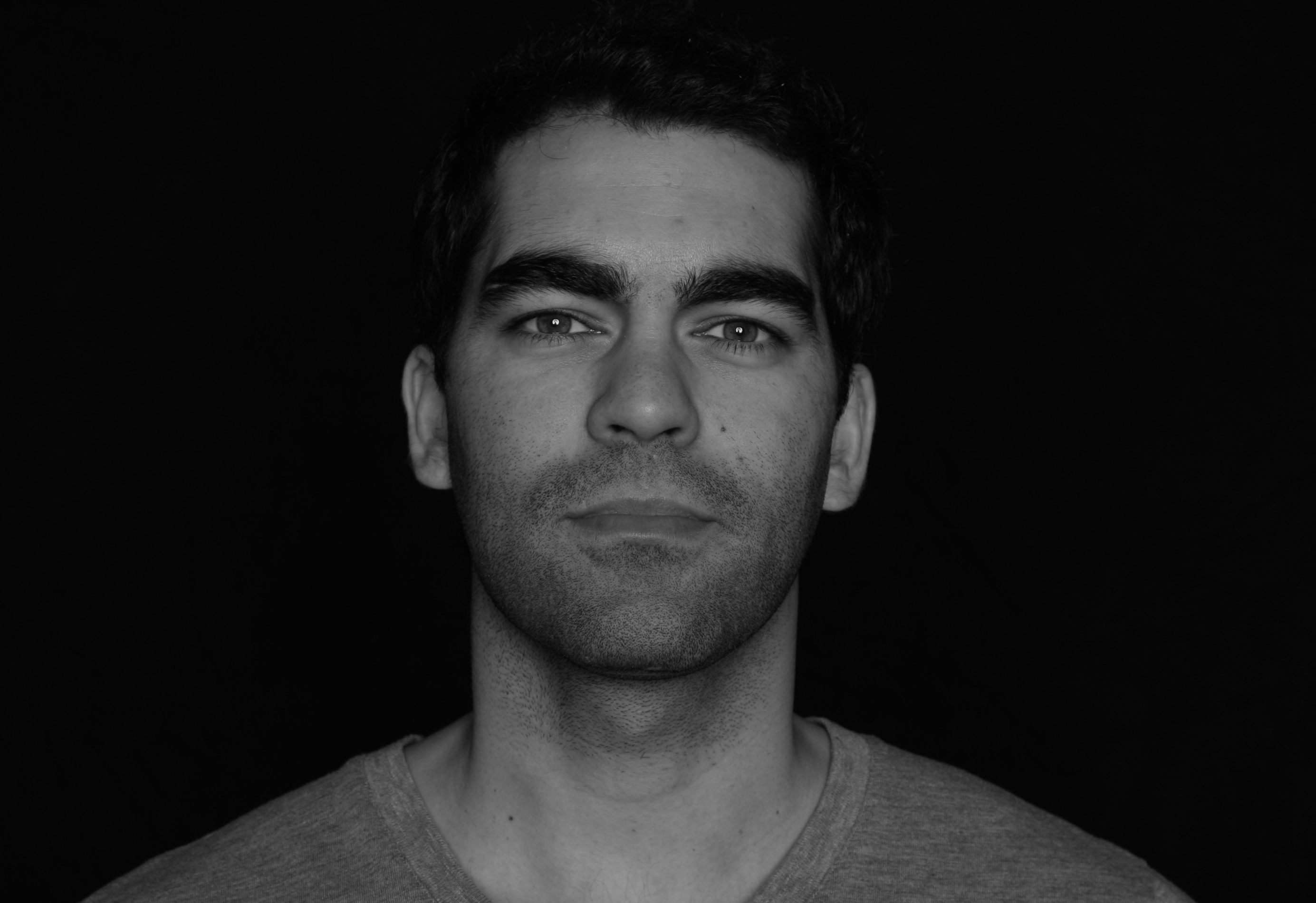

With a new LP,partly conceived at Jaeger and an upcoming show for Musikkfest, it was about time we talk to synth wizard True Cuckoo.

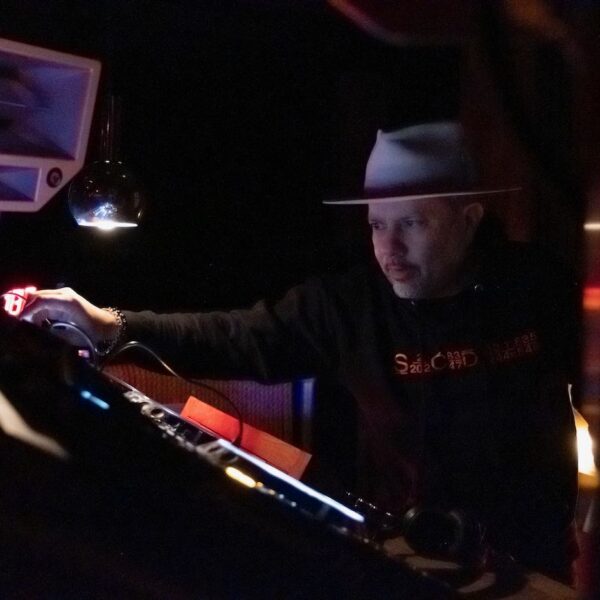

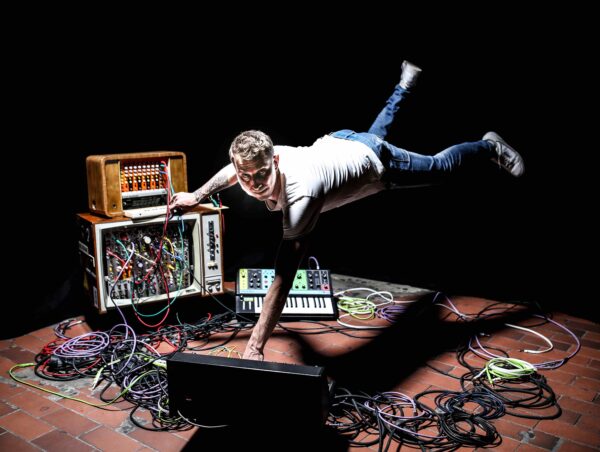

It’s early in Jaeger’s basement and it sounds like I’m trapped in an augmented reality version of Tron. Laser-like sounds cut through the air in syncopated “pews” and “glitches” while a drum machine stutters through its arrangement. Broken beats unfold like whirling dervishes, while rhythm patterns take on unexpected shapes. This is the sound of synth wizard True Cuckoo.

It’s March 2023 and I’m hearing the conception of a new LP; I just don’t know it yet. It’s coming into focus around the bleeps and squeaks dissipating around me, but it’s still in its nascent form, a mere seed of what it would become. Beyond the rumbling drum machines shaking the infrastructure of the Funktion One sound system, there is something familiar about this sound, but I can’t quite put my finger on it…

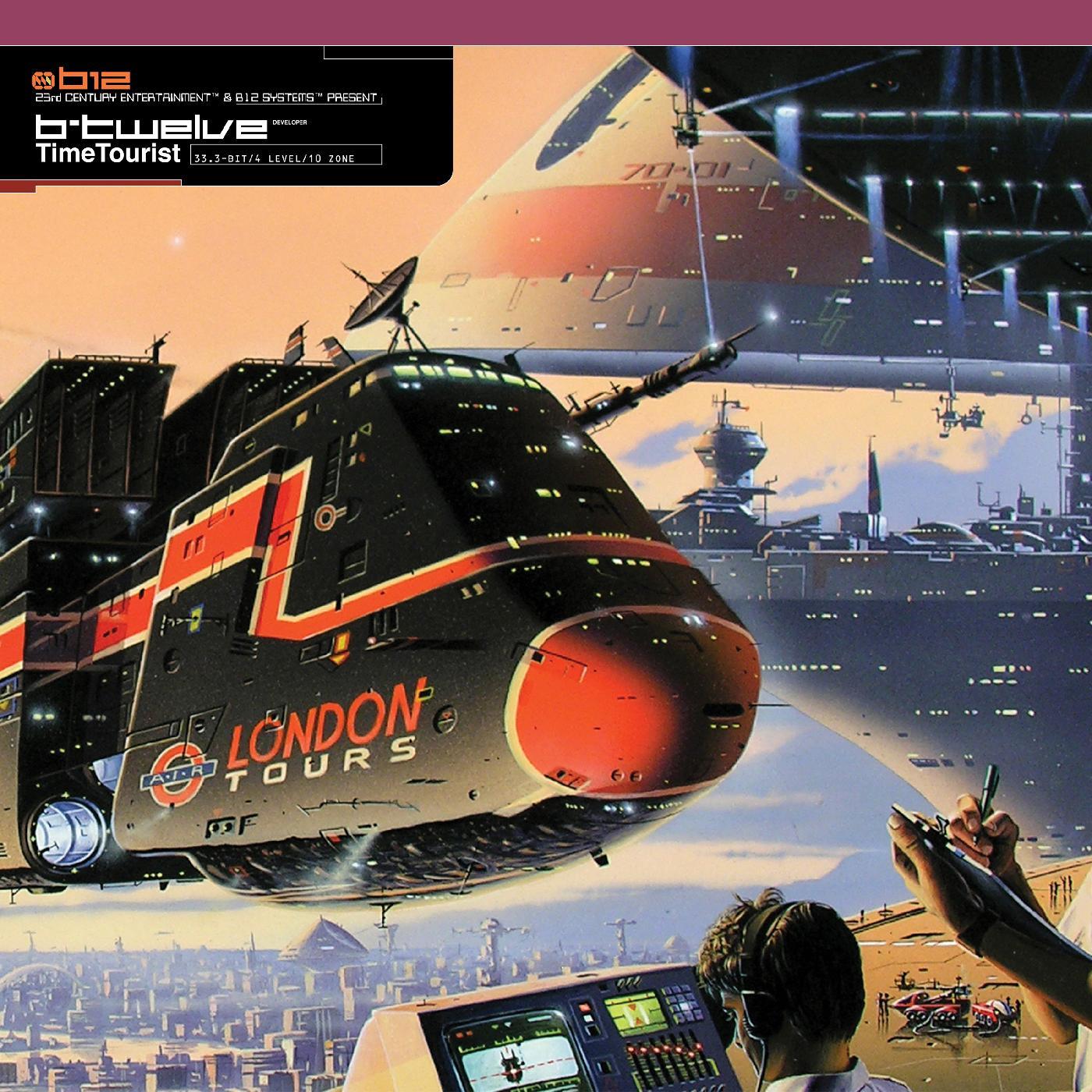

It’s 2025 and I’m listening to Non-Binary Code by True Cuckoo. I’m on the track “Bitcore,” and it’s stirring some core memory. It’s more than just the memory of the artist playing the song a couple of years before. No, it’s more wistful and nostalgic than that. There’s a bouncing melodic theme that resolves into a long sweep and I’m transported back to my youth.

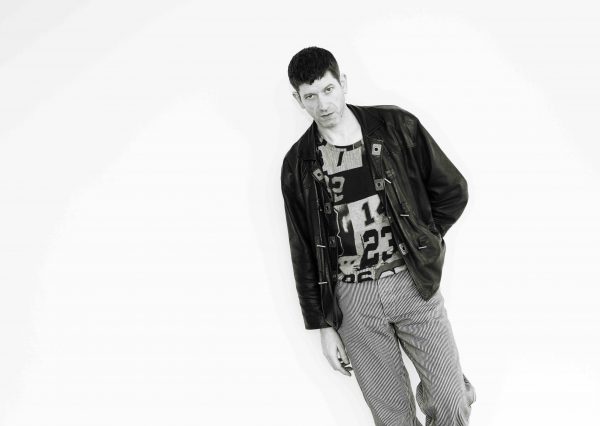

It’s the early nineties and I’m sitting on the floor, with a game console at my feet, and this is the sound of True Cuckoo’s new LP. Andreas Paleologos (True Cuckoo) also “grew up in the era of (Super Nintendo) and Sega Megadrive.” Whereas it’s a faint memory for most of a generation, I’m not surprised that it “inspired” Andreas and even “to this day,” still inspires.

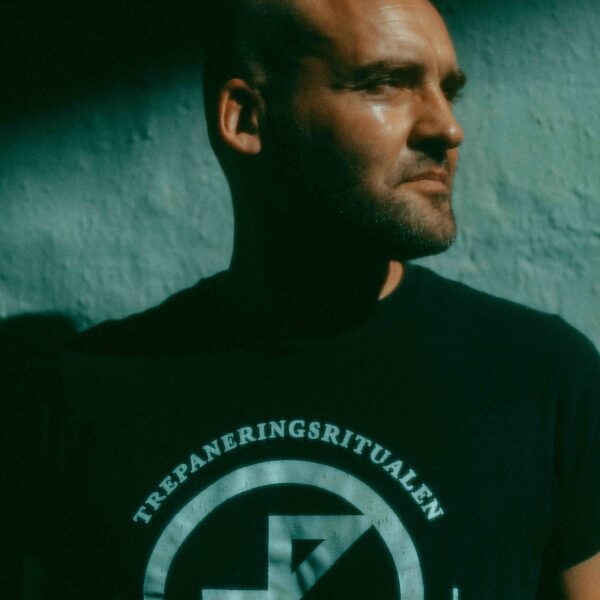

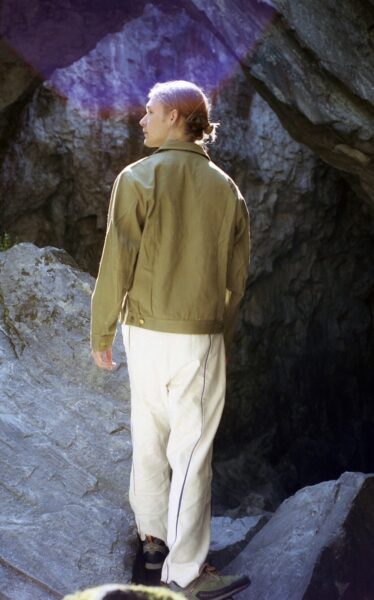

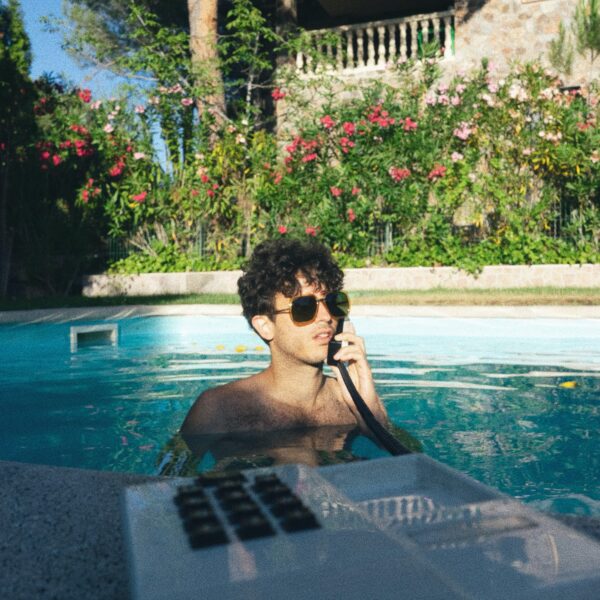

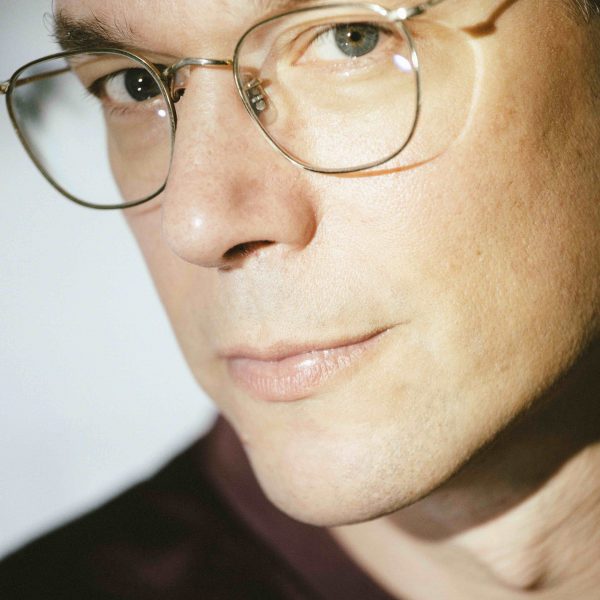

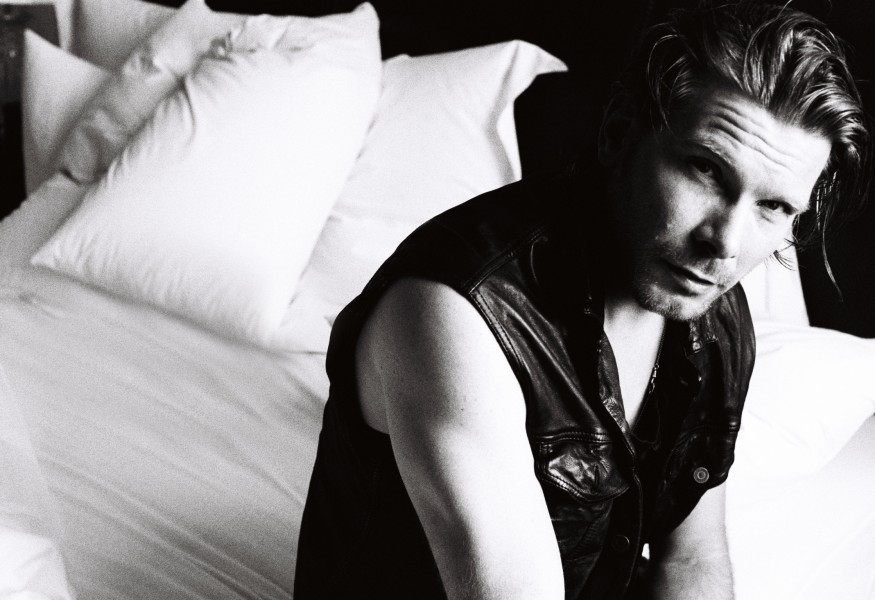

Andreas has a sonorous accent; it’s a blend between his Swedish sing-songy inflections and delicate English pronunciations. He’s just moved out of Oslo city centre, and when I phone him up he’s enjoying a slice of suburban sunshine on an early spring day. His voice lilts like a low frequency oscillator in one of his songs, mimicking a looping crescendo as a game waits for the player to hit start.

“It’s that melodic landscape that I reach into when I create music,” he continues as we get stuck into his latest LP, Non Binary Code. Before the album, Andreas had this sonic image of “a soundtrack to a fictional game that doesn’t exist.”

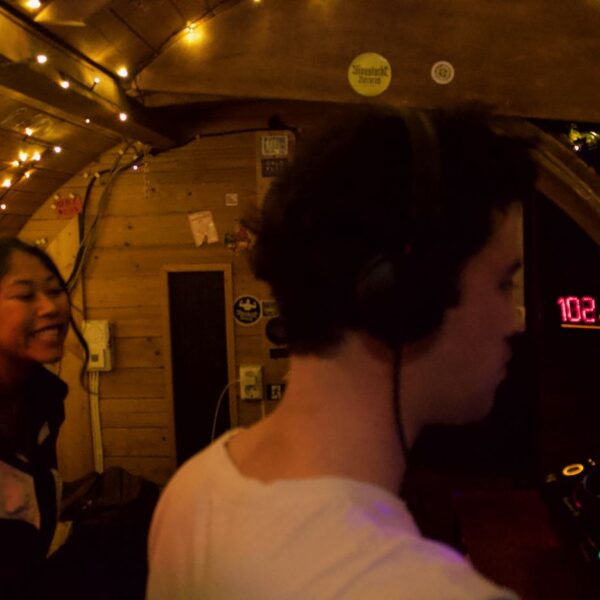

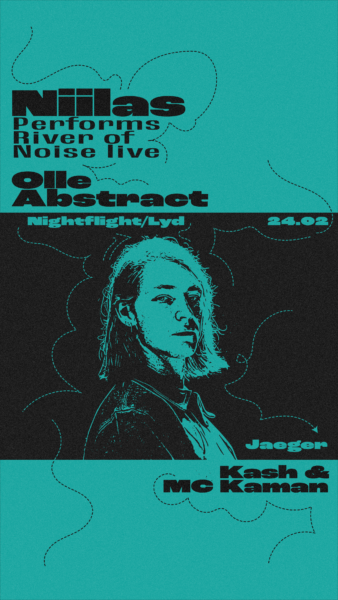

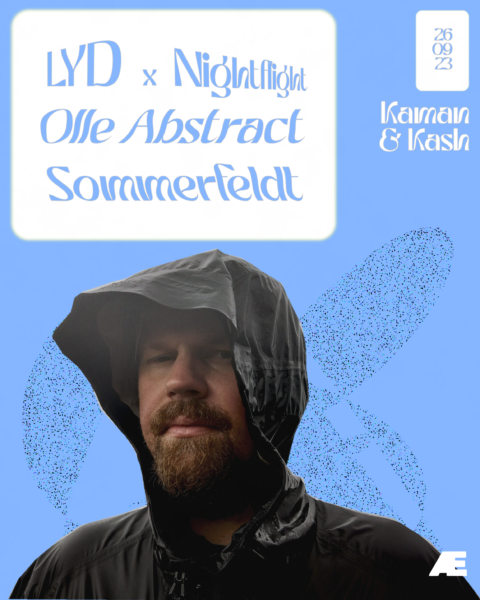

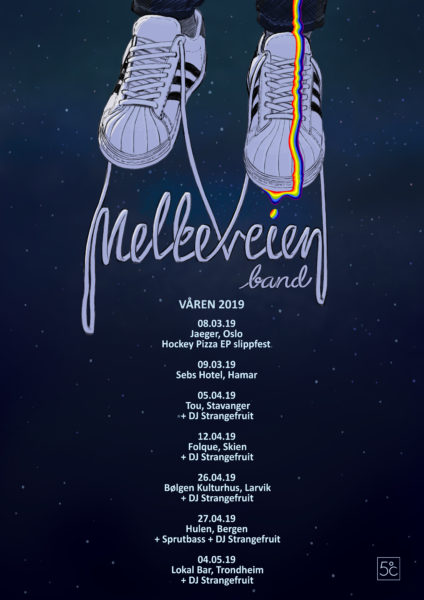

Originally commissioned as a live performance at the Fredrikstad animation festival – as accompaniment to his animation – the show, and eventually the album, found its shape as it was later re-created at Jaeger. At the behest of Kaman Leung, True Cuckoo’s performance at Jaeger in 2023 was the push the show needed to go from vague idea to full-fledged concept.

Faced with the sound system in the basement he thought; “If I’m playing here on this system I need to know what works for this system, because it’s kind of amazing.” He “tried the embryo of this LP,” and was immediately struck by the sound. “This sounds incredible down here,” he exclaimed. The idea for an album then took shape with Andreas realising: “This is what I have to finish.”

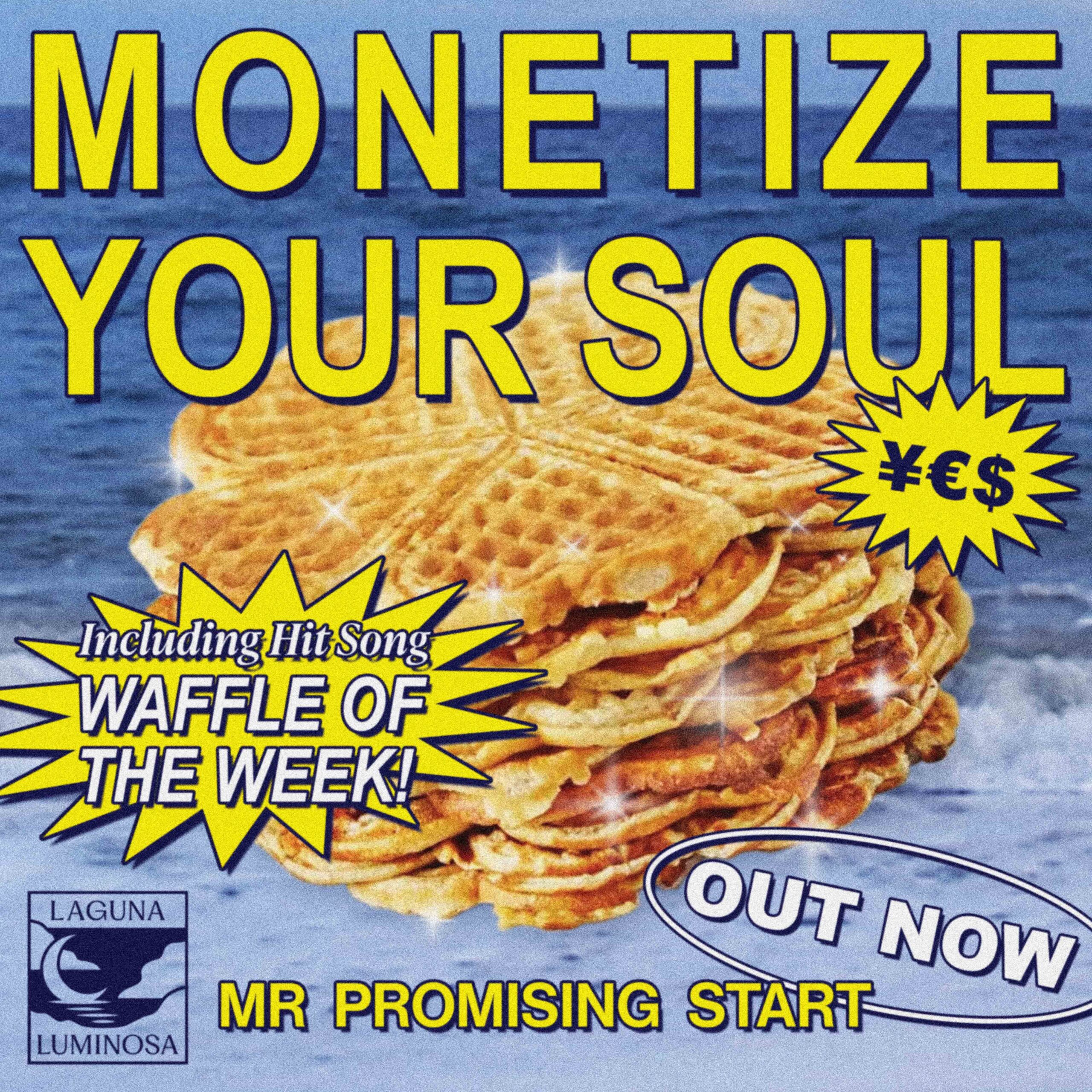

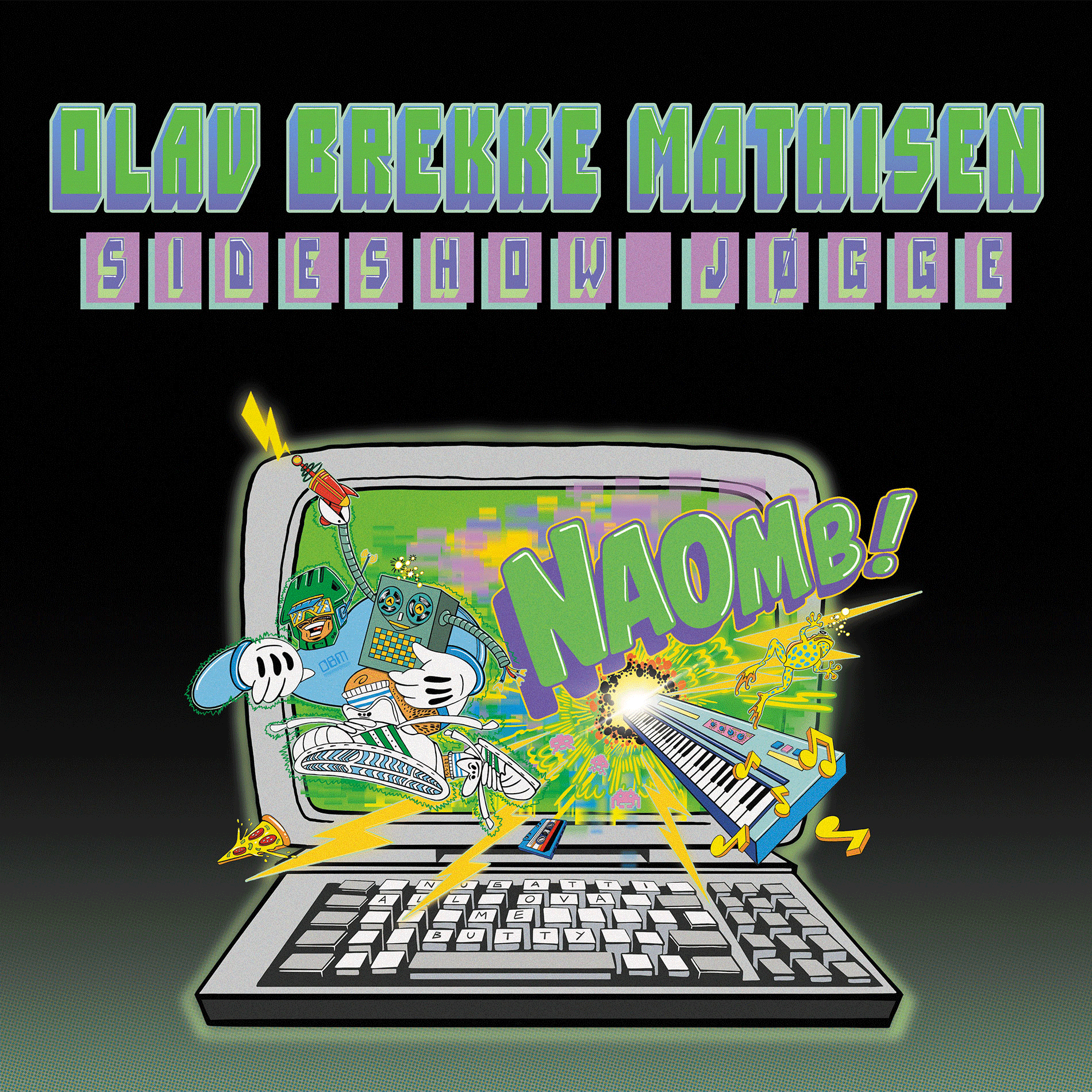

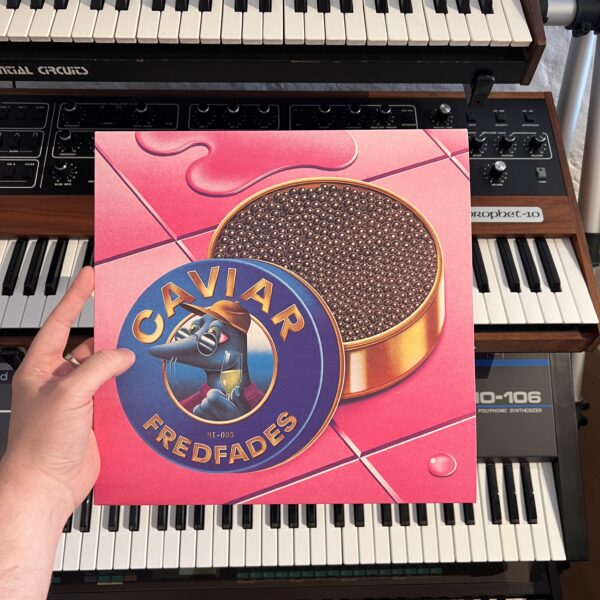

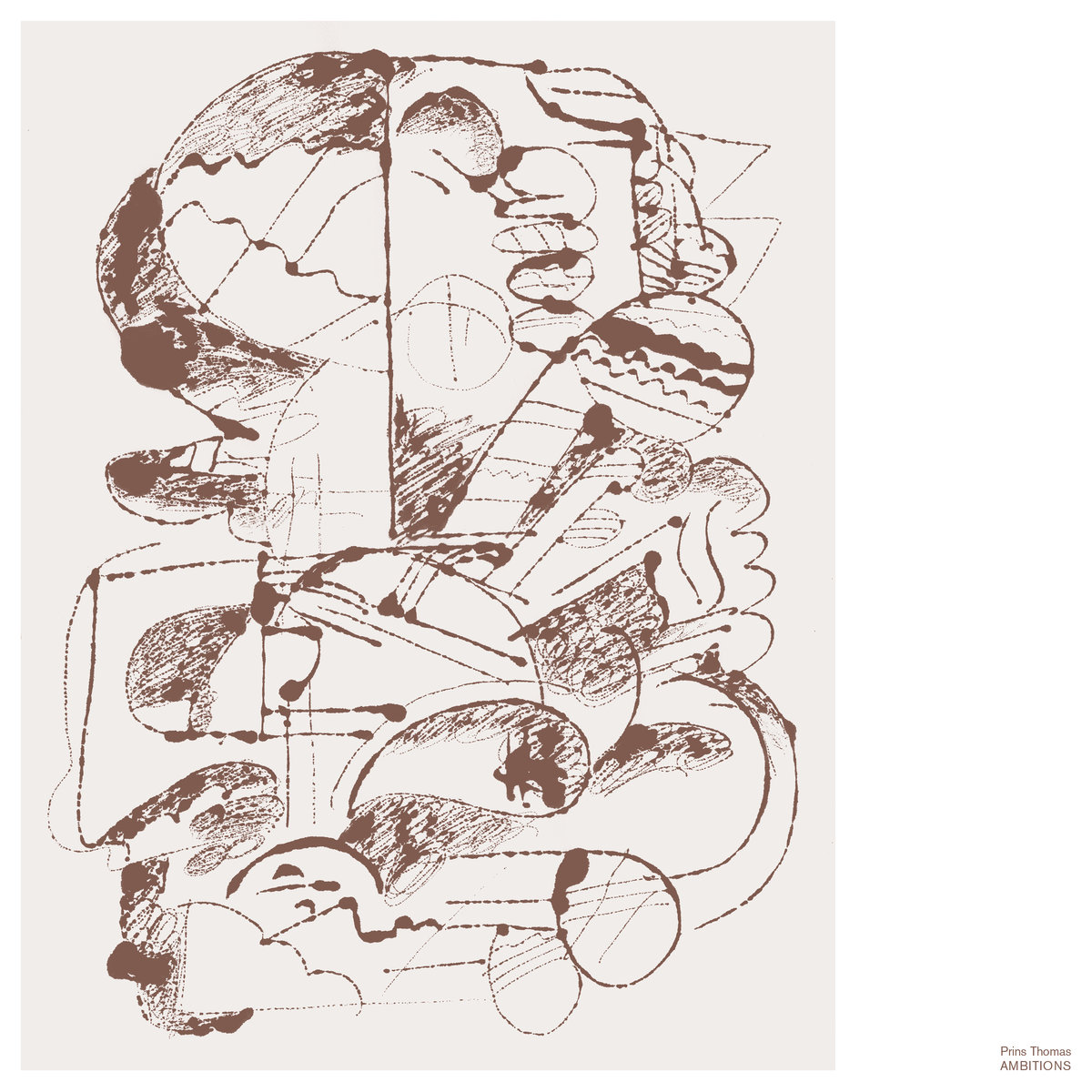

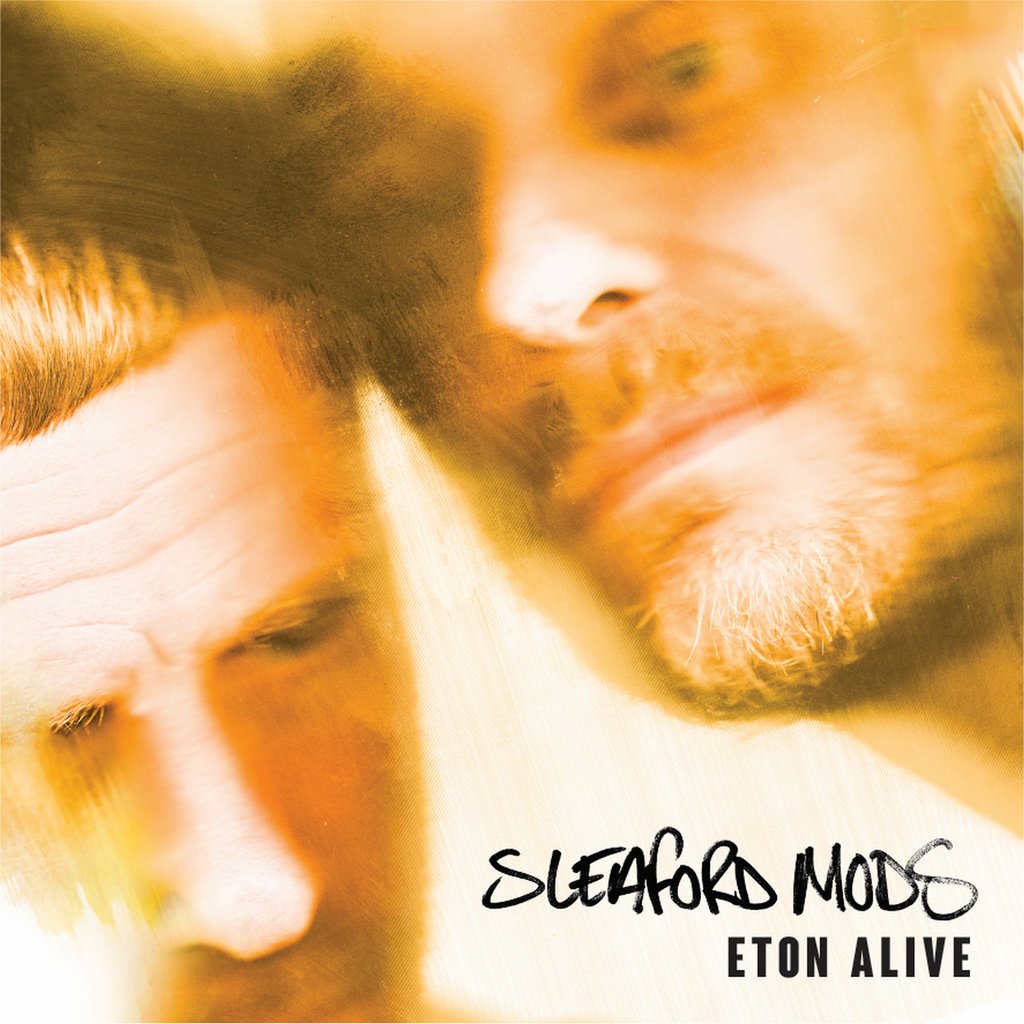

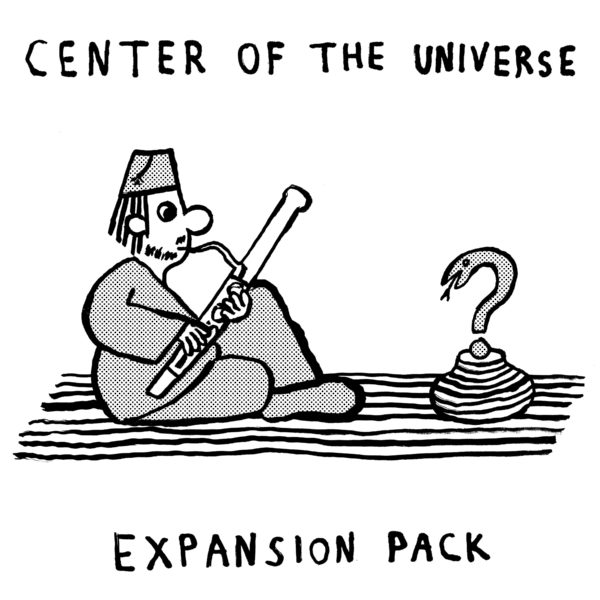

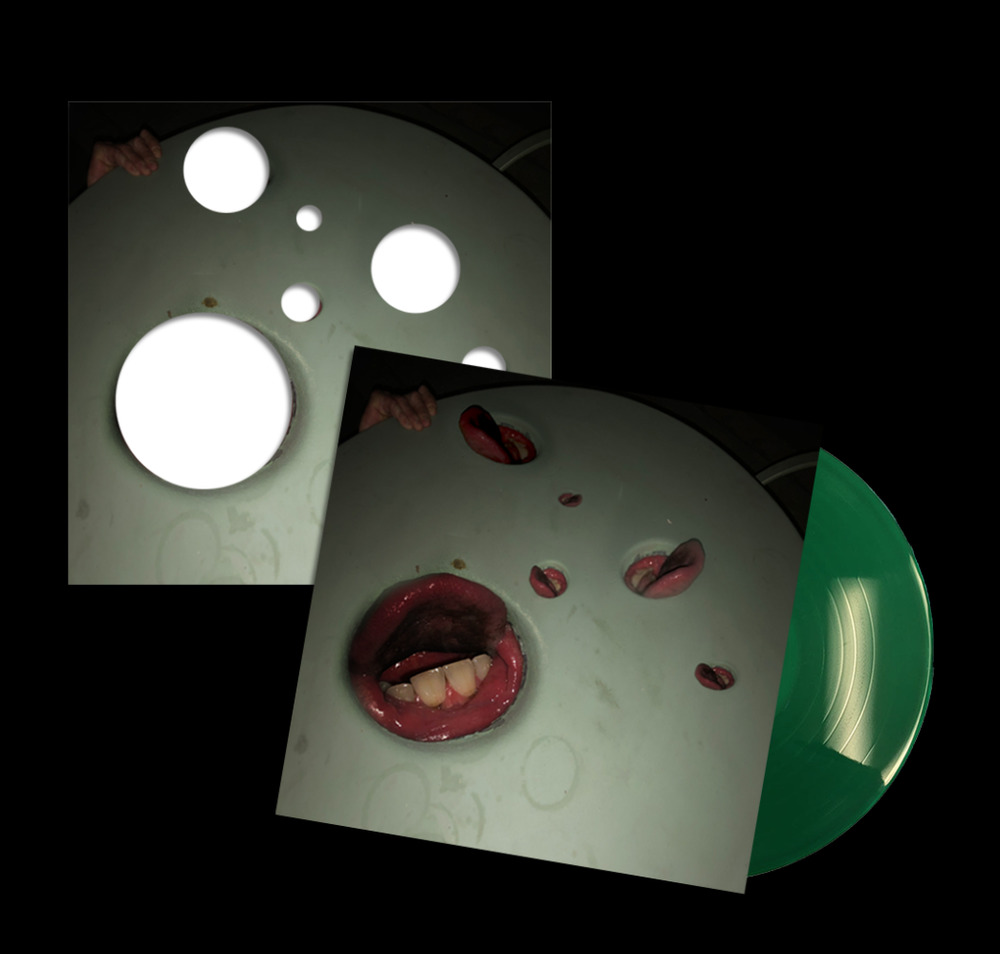

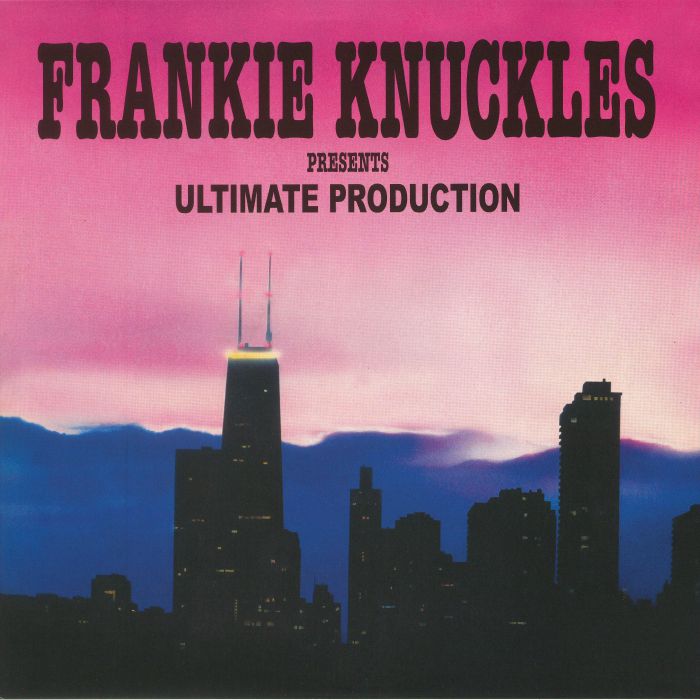

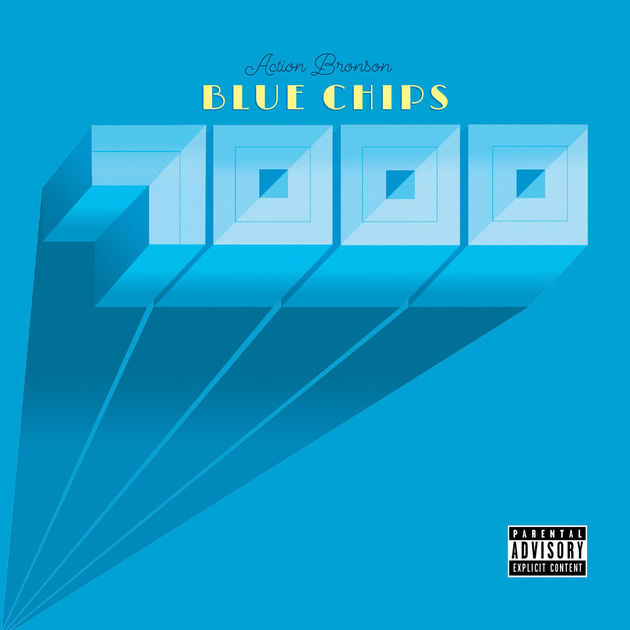

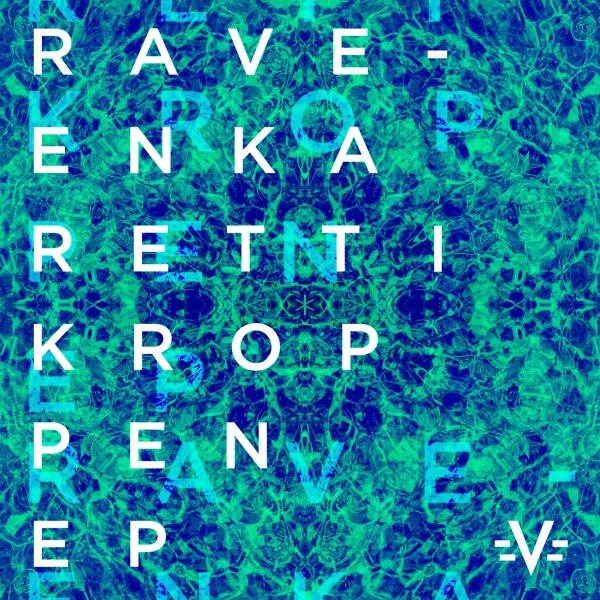

The result is Non Binary Code. Initially released in 2024 for digital platforms, it has recently been re-issued for the vinyl format. The vinyl version includes an immersive comic book gatefold; a two-month endeavour created by the artist as an extension of that conceptual theme behind the record.

Non Binary Code never lost sight of the immersive video game feel, even with certain tracks taking on a more “club-oriented” feel. At its most energetic through “Blitterate” – a brisstling drum and bass arrangement – it stops and breathes at phrases, like a character crossing over the threshold of a new level, or waiting for the boss to arrive in the next frame.

At its most serene, tracks like “Tsuki Ga” or “Mem Leak” touch on esoteric melodic arrangements evoking sonic themes from the likes of Castlevania. It’s something exotic and lovely to break the harshness of the limitations of those early gaming console’s sounds, where Andreas’ own musical interests first took shape.

As a teen, he and a group of friends were early in exploring the new technology of consoles, “aiming to create games for the Commodore Amiga.” He claims he was never really a programmer and that his involvement in these games was more universal, “doing a little bit of everything,” including making the music.

He had always, however, held an interest in music, tinkering with the electric organ at home or playing his Grandma’s piano in rural Sweden. At school he had music classes, and while he would always be playing and writing music, including his early attempts on the Amiga’s tracker software, it never developed much beyond a hobby.

Instead, he took to the animation aspects of these games, eventually working in the video game industry as an animator and “making video games professionally.” Music remained an interest, however, and while he could indulge those interests in the odd compositional contribution to some of the games he worked on, Andreas has always felt it was something he did just “for fun.”

By the mid-2000s, that all changed when he met a young Jenny Hval. “She was called Rockettothesky,” at that point and together with her producer, they put together a “little band,” “travelling Norway, and playing all the festivals,” off the back of her debut LP. Andreas “got so hyped by that,” and decided “this is really what I want to do.” Cuckoo was born, and then later matured to True Cuckoo – “because there turned out to be several bands on Spotify called Cuckoo.” He released his first LP in 2009, but “nothing happened and I got no traction.”

Where most would resign their efforts to the waste bin and go back to their day job, Andreas had something else in mind. He had been an early adopter of YouTube, uploading his animations to the site in the hope that those would “gain some popularity.” As his urge to make and share music grew stronger, however, he thought: “Why don’t I just do this?” and True Cuckoo took to the web.

Today, it’s a channel for people interested in the tools for creating electronic music, but with its esoteric feel dictated by Andreas’ own interests, it’s for those that want to delve deeper. It goes beyond the standard review and the obvious, to instead focus on “a musical goal when explaining how things work.”

Today, the channel has over 200,000 subscribers, but he’s not just another man with beard twiddling knobs on a screen. His slow, patient voice seems to explain with ease even the most exhausting menu dives.

Andreas had always had a knack for these technologically demanding instruments. After learning how to make music on the Amiga’s tracker, he bought his first synthesiser as a teenager. He had clearly found some instinctive knack for the machine, based on his early Amiga experiences and organ tinkering, but watching him perform today either live or on YouTube, it’s clear that Andreas’ knowledge extends to some of the more intimate features of some of the world’s most exotic and peculiar machines.

Today, his YouTube channel is dominated by quirky synthesisers and tools that flip traditional musical creation on its head. Tools like the logic-defying OP-1 or the challenging, manual-craving Elektron Octatrack, and it appears that it’s always these unusual, often scary machines that attract him.

By way of explanation he tells me about a recent visit to the German electronic music instrument messe , Superbooth, where he gravitated towards the Korg Berlin acoustic synthesizer Phase 8. “It’s a supercharged kalimba,” he explains with some delight, “a cool little thing that’s outside of a typical electronic instrument now.”

It’s these kinds of things that will usually show up on his channel and eventually his own music. “It’s always about what I’m finding interesting,” he insists. “I only show stuff that I’m interested in using myself.” He says he is inundated with requests from big manufacturers to feature instruments on his channel, but finds that he has to turn almost all of it down. “It sounds like I’m on my high horse, but for the whole time running my channel, I’ve never considered myself a reviewer.”

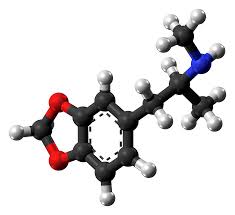

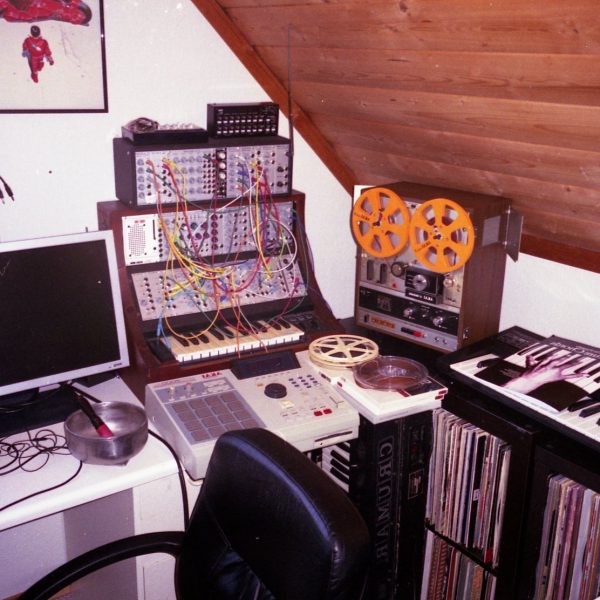

The channel has a tendency to “gravitate towards stuff that I find inspiring.” This is hardly an exaggeration, and in Non Binary Code, he turned exclusively to a machine he’s featured on the channel more than once, the Elektron Digitone. A frequency modulation synthesizer and groovebox, it has the ability to create those exotic organic tones that pluck at the central melodies of themes like “Mem Leak,” or make those erratic bit-crushing sounds of “Bitcore.” “I made everything on this one machine,” he says.

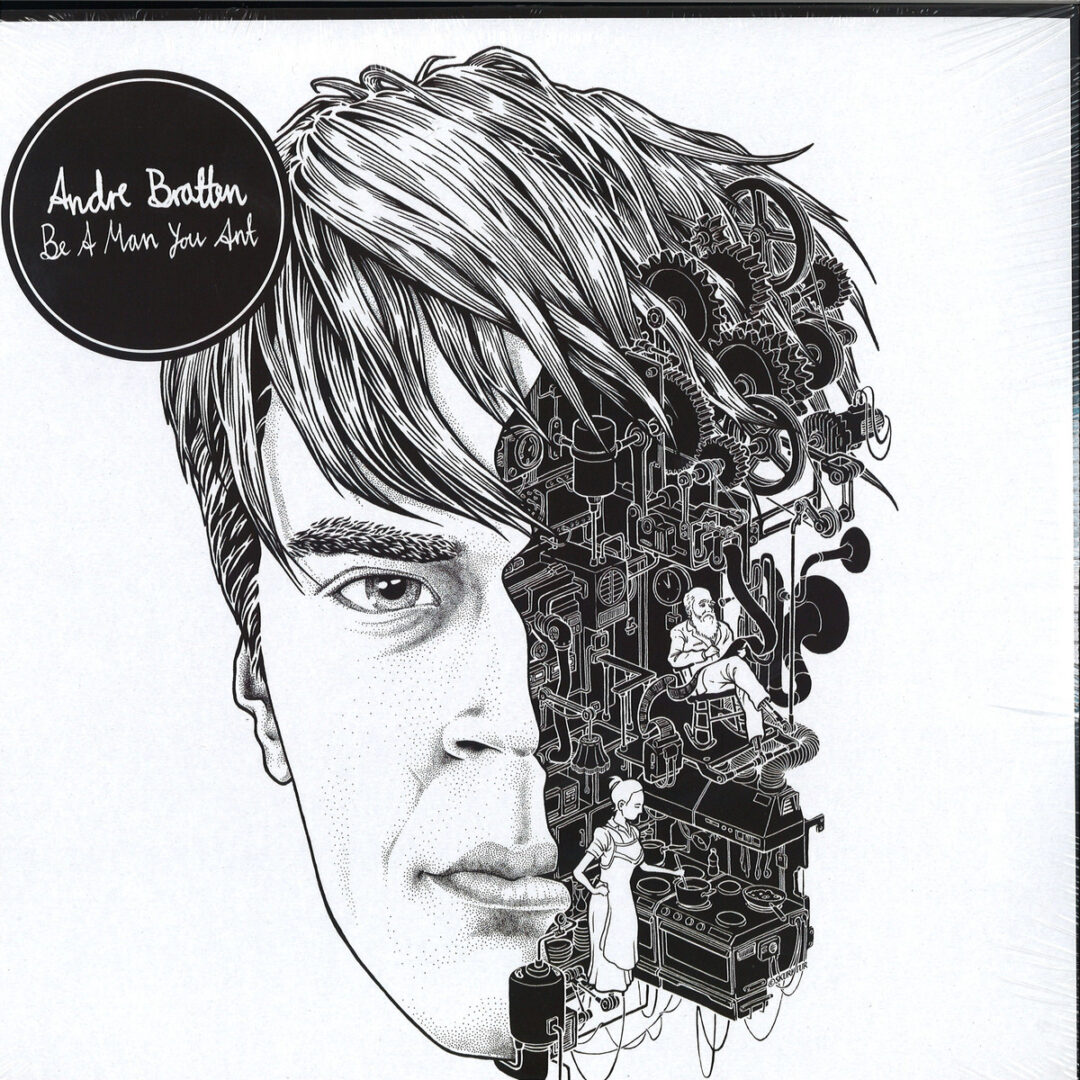

He was particularly drawn to the “algorithms that are extremely close to the Sega Megadrive,” as the video game concept manifested in his mind. Even though these thematic ideas are very strong on Non Binary Code, there is still something of a sound to True Cuckoo’s music. This album is very much a continuation in sonic aesthetic from his last two albums, I’m Not a DJ and Not Pop, and the glitchy, erratic expressions are central to his appeal.

As True Cuckoo, Andreas avoids any dogmatic or stylistic traits in what is a truly preternatural sound. There is no preset or obvious generic cue, and everything he does sounds experimental; not in some naïve and puerile sense of exploration, but in a knowledgeable and considered approach.

“I enjoy taking other adventures and arriving at new sounds,” says Andreas of his approach. He doesn’t always have to be making music either. He’s quite happy just exploring the limits of his equipment in search of new sounds. “I really like to create my own sounds from scratch,” and although he makes those sounds available to anybody through his sample packs, you won’t find many taking those machines in these directions.

It’s easy to get stuck into the finer details of synthesizers and music machines with Andreas. He engages with his topics like a teacher to young children, and can make sense of even the most obscure machines. Our conversation starts to sound like one of his YouTube videos as we turn to his current love affair with UDO Audio synths.

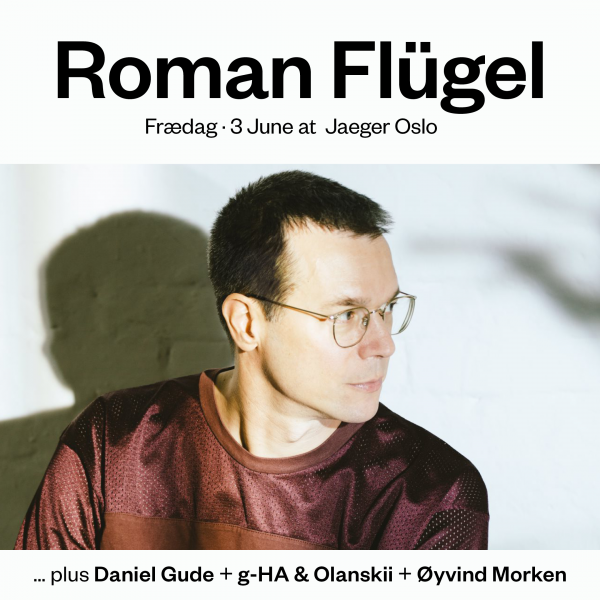

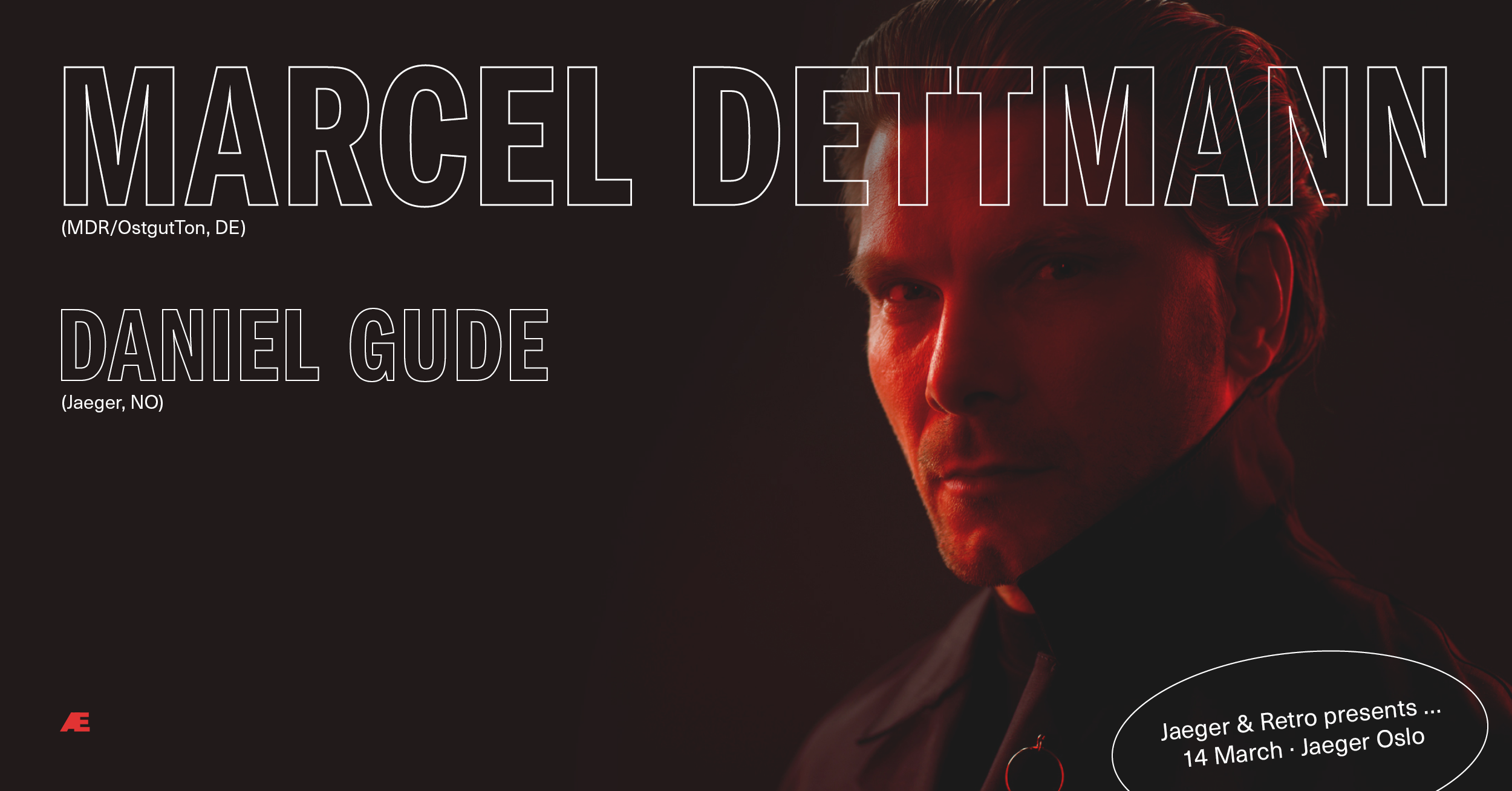

While he won’t be bringing that particular slab of synthesizer out to his next appearance at Jaeger’s for Musikkfest, he is threatening to bring “two devices.” He’ll expand on the album and “play some of the new stuff.” In a way it’s kind of a homecoming for Non Binary Code as an LP partly conceived at Jaeger, as it comes full circle, but it’s also an opportunity to take a new adventure into other sounds.

“That’ll bring closure for sure…” he says about performing Non Binary Code pieces at Jaeger, but you get the sense he’s already looking towards the next album. Who knows, maybe we’ll hear the first echoes of something new.

How has it informed your work beyond the DJ booth and in the studio?

How has it informed your work beyond the DJ booth and in the studio?

What do you remember of the nights at Space @ Bar Rumba?

What do you remember of the nights at Space @ Bar Rumba? How did you and Honey start working together?

How did you and Honey start working together?

You mentioned, Garage was big when you were teenagers. Is that around the same time you started to make music?

You mentioned, Garage was big when you were teenagers. Is that around the same time you started to make music?

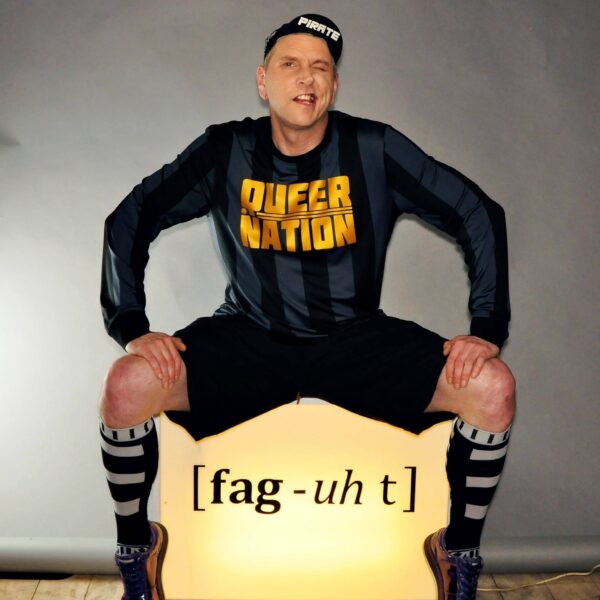

James doesn’t feel queer is a “sexual statement,” but rather an ideology. “I know cis straight woman who identify as queer,” he says as an example. For James, queer is about a “rejection of patriarchy” and a the celebration of “alternative lifestyles” on dance floors. “As long as they bring love and joy to the dance, then everybody is welcome,” insists James. Even though the party they “do in New York is a different crowd to the one in London and the one in Berlin is different to both of those,” that queer element remains at its core and James “love

James doesn’t feel queer is a “sexual statement,” but rather an ideology. “I know cis straight woman who identify as queer,” he says as an example. For James, queer is about a “rejection of patriarchy” and a the celebration of “alternative lifestyles” on dance floors. “As long as they bring love and joy to the dance, then everybody is welcome,” insists James. Even though the party they “do in New York is a different crowd to the one in London and the one in Berlin is different to both of those,” that queer element remains at its core and James “love

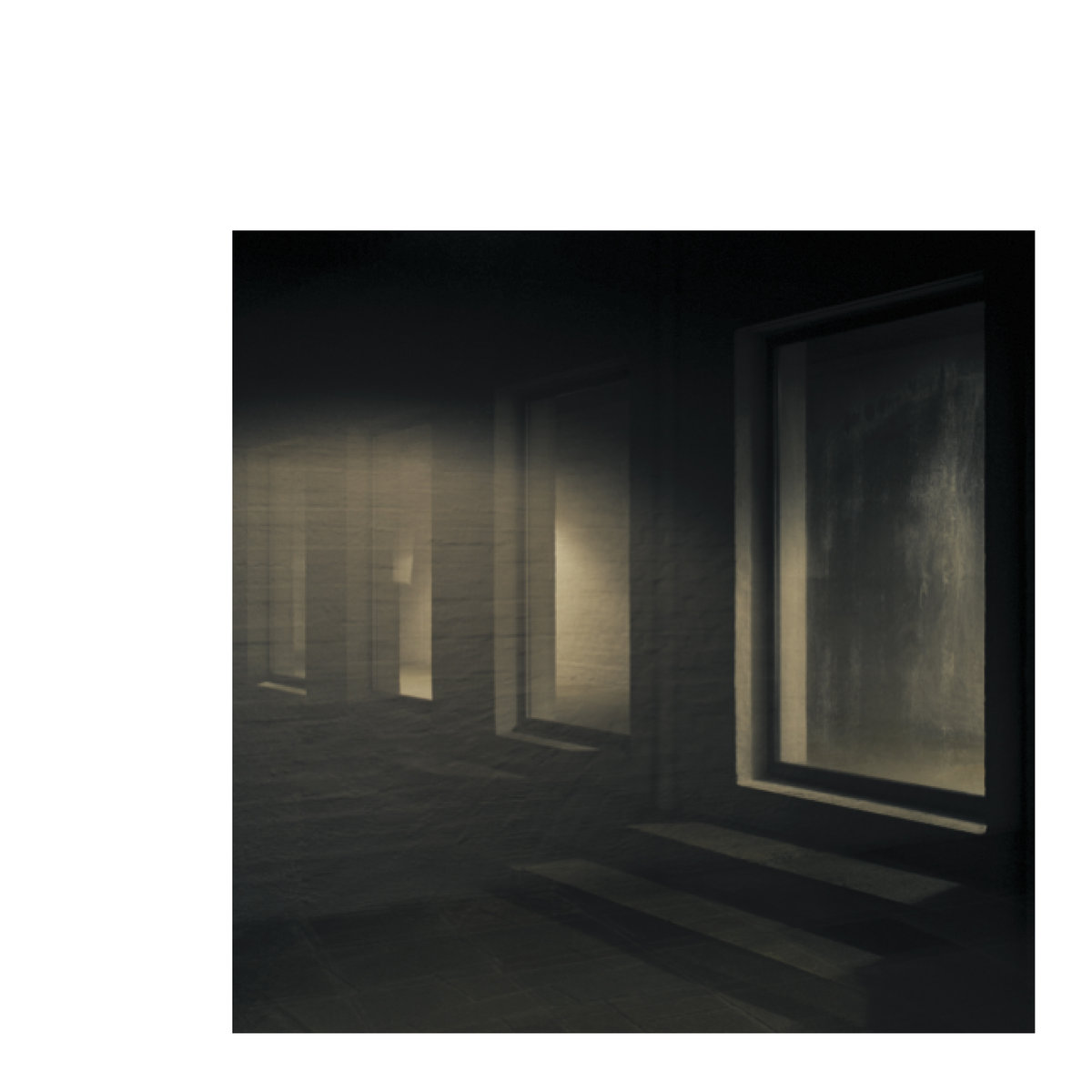

Tell me about WINDOWS. Is it an album and/or a live show?

Tell me about WINDOWS. Is it an album and/or a live show?

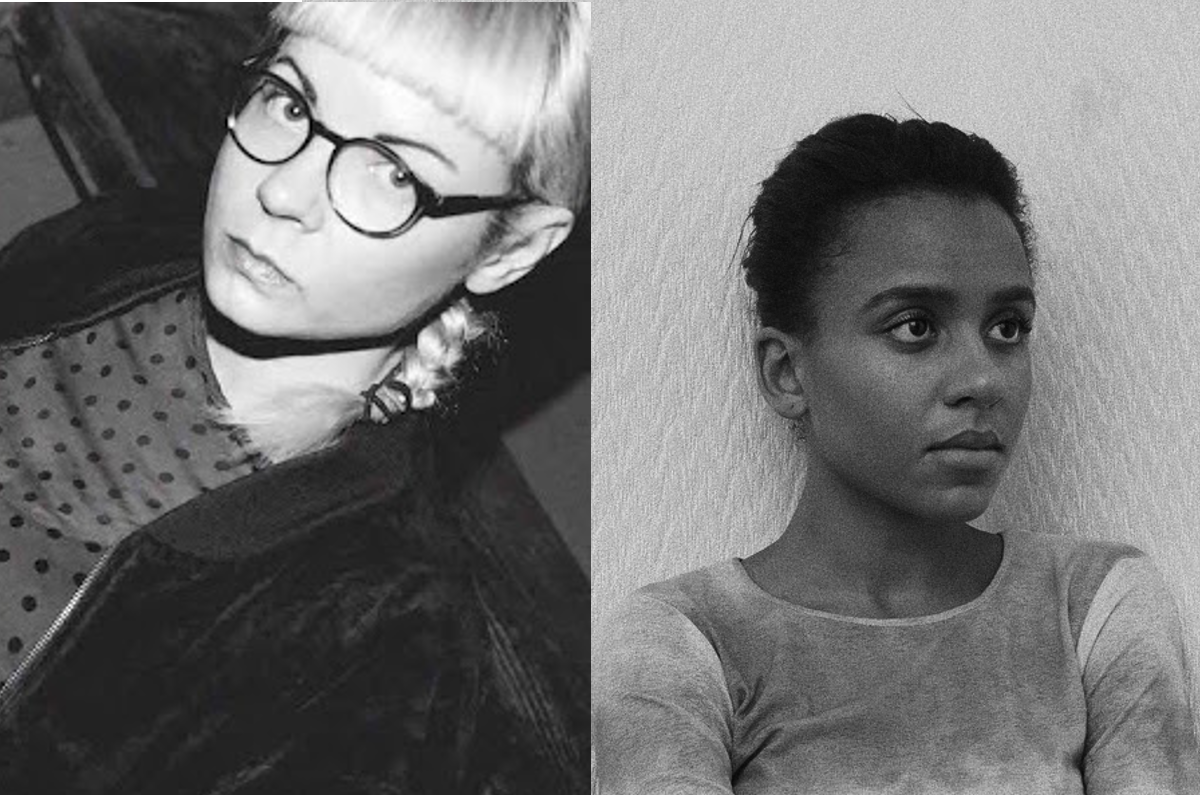

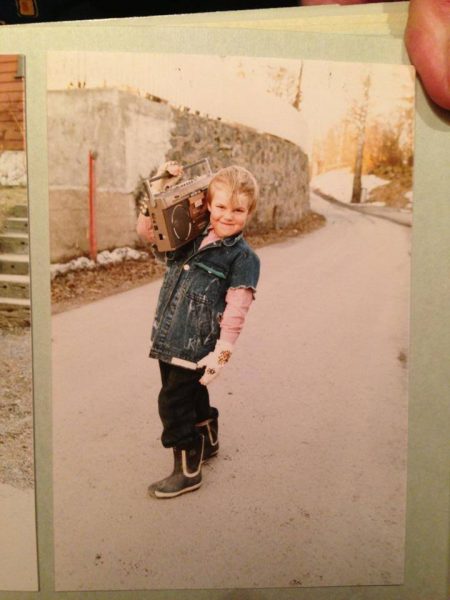

Ida and Naomi both grew up in what they consider a “small town” called Sandefjord. Both had taken an early interest in music albeit from different points of view. While Ida was “drawn into singing very early,” Naomi was an avid listener, consuming all she can from Beyonce to Dimmu Borgir. At around the age of 11 Naomi’s dad built her a dance studio in the basement with “some cheap speakers and different kinds of disco lights” encouraging the impressionable youth towards electronic dance music. She would be “dancing like a crazy person to Benny Benassi” in her basement enclave she remembers fondly today.

Ida and Naomi both grew up in what they consider a “small town” called Sandefjord. Both had taken an early interest in music albeit from different points of view. While Ida was “drawn into singing very early,” Naomi was an avid listener, consuming all she can from Beyonce to Dimmu Borgir. At around the age of 11 Naomi’s dad built her a dance studio in the basement with “some cheap speakers and different kinds of disco lights” encouraging the impressionable youth towards electronic dance music. She would be “dancing like a crazy person to Benny Benassi” in her basement enclave she remembers fondly today.

You’re talking about the early nineties?

You’re talking about the early nineties?

Wilkes

Wilkes 13 years is still a long time for a club night, especially at that time, when everybody was going from one thing to the next quite quickly. How did you maintain that excitement around it for so long?

13 years is still a long time for a club night, especially at that time, when everybody was going from one thing to the next quite quickly. How did you maintain that excitement around it for so long?

You got pigeonholed as a DJ, somewhat unfairly, in that Deep House trend after “Your Everything.” What effect did it have on what you would do next and how did you eventually sidestep it as a DJ?

You got pigeonholed as a DJ, somewhat unfairly, in that Deep House trend after “Your Everything.” What effect did it have on what you would do next and how did you eventually sidestep it as a DJ?

Who is that?

Who is that?

Lars grew up in the

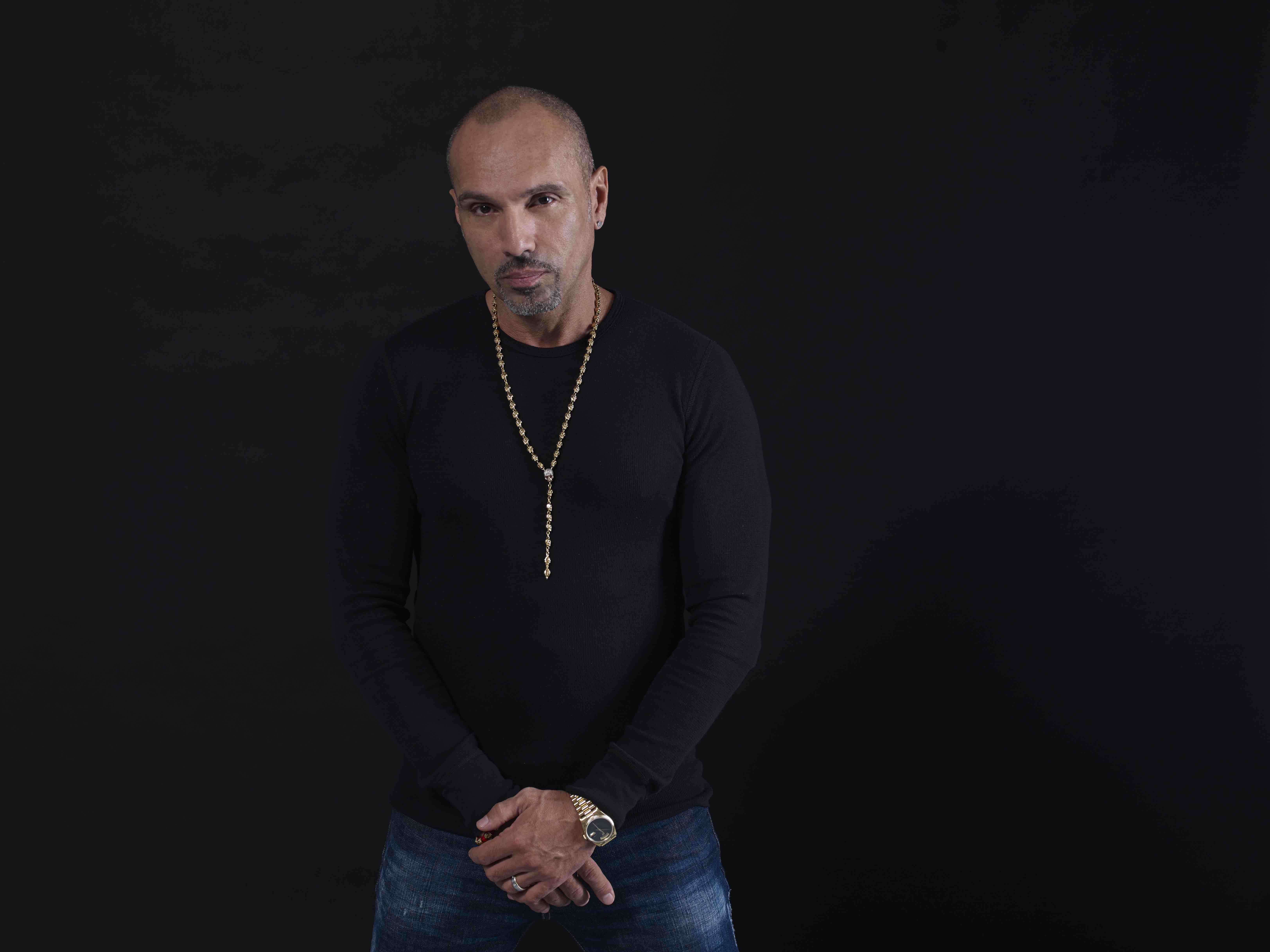

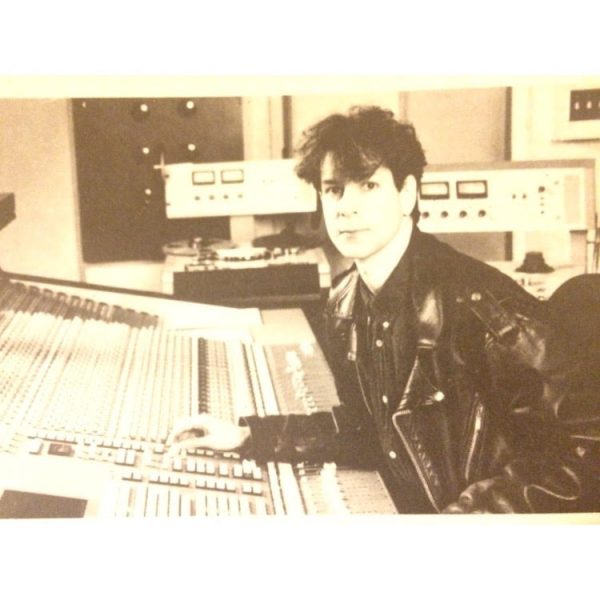

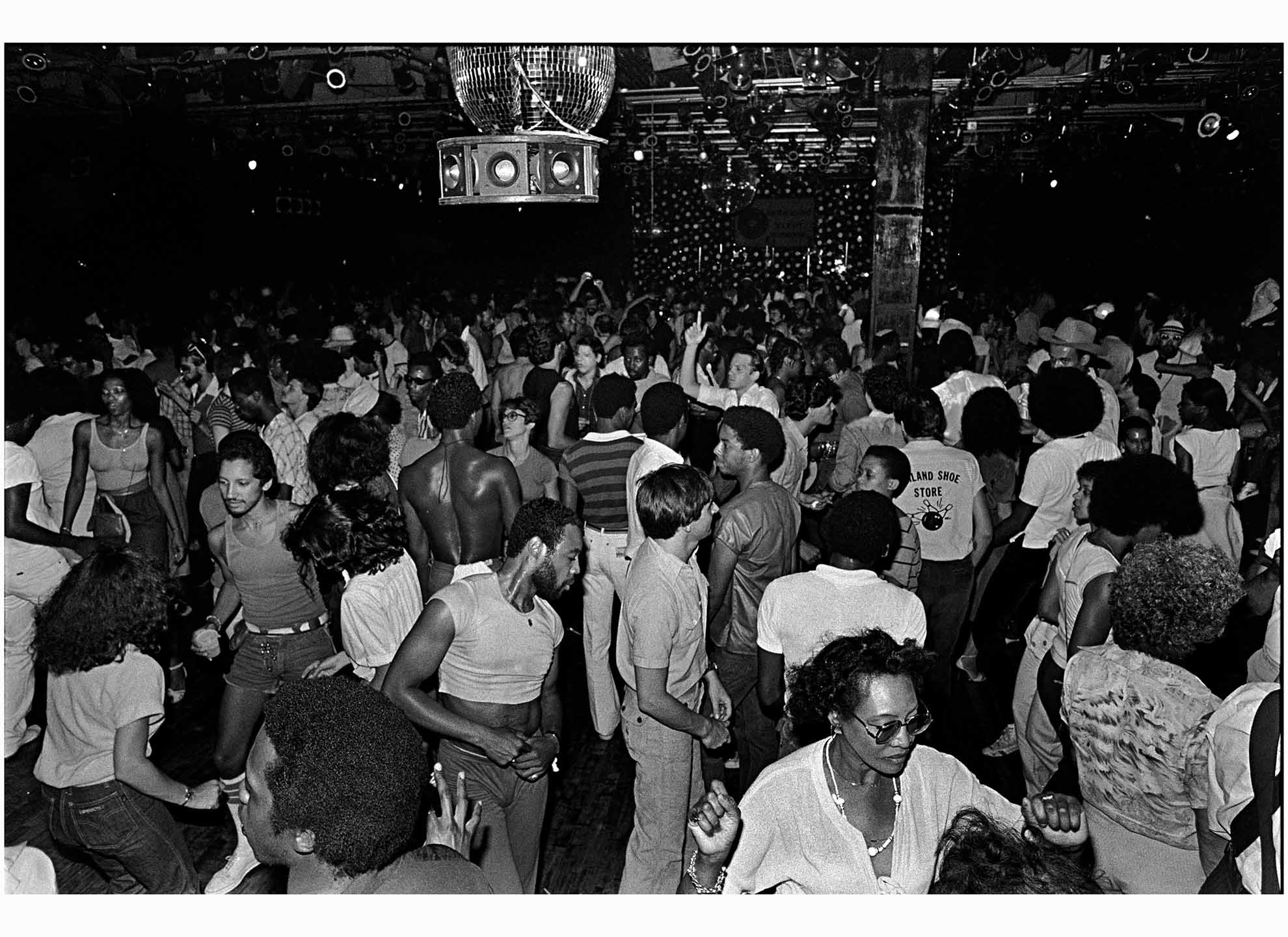

Lars grew up in the At 13 he had heard his first DJ playing Disco records consecutively, and by 15 he went to his first club and bought “Ten Percent“ on Salsoul. The speaker hanging out the window soon developed into a party in his apartment, and requests to play at other people’s house parties followed as he became a local mobile Disco music of some repute. “I just loved the music, it was just everything for me,” he remembers. At 18 he had made something of a career out of it, playing mostly commercial music, before somebody dropped “a stack of what they called Loft records” at his feet. “I was like ‘Whoa, what is this sound?’” It was a selection of expensive, limited press- and imported records, the kind of which they had been playing not only at the Loft, but also Paradise Garage. Although Morales had not yet been to either club, since they were strictly private clubs, he started making inroads as a dancer frequenting venues like Paradise Garage and the Loft through acquaintances with memberships, and eventually befriending people like Mancusso and DJ Kenny Carpenter. It was through Carpenter that he was inducted into a record pool, the first organisations that supplied DJs with new, unreleased music for the club, and it was through this pool that he would have his first major break as DJ.

At 13 he had heard his first DJ playing Disco records consecutively, and by 15 he went to his first club and bought “Ten Percent“ on Salsoul. The speaker hanging out the window soon developed into a party in his apartment, and requests to play at other people’s house parties followed as he became a local mobile Disco music of some repute. “I just loved the music, it was just everything for me,” he remembers. At 18 he had made something of a career out of it, playing mostly commercial music, before somebody dropped “a stack of what they called Loft records” at his feet. “I was like ‘Whoa, what is this sound?’” It was a selection of expensive, limited press- and imported records, the kind of which they had been playing not only at the Loft, but also Paradise Garage. Although Morales had not yet been to either club, since they were strictly private clubs, he started making inroads as a dancer frequenting venues like Paradise Garage and the Loft through acquaintances with memberships, and eventually befriending people like Mancusso and DJ Kenny Carpenter. It was through Carpenter that he was inducted into a record pool, the first organisations that supplied DJs with new, unreleased music for the club, and it was through this pool that he would have his first major break as DJ.

The first release on the label came via KiNK, with the aptly titled “Home,” and in that record we find similarities to KiNK’s music from “Under Destruction” as tracks play on similar rhythmic and melodic themes, distilled down from traditional music, with titles like The Clock and The Grid redefining the concepts contained in their titles for western ears. Accompanying the release and future releases from a small, but dedicated community of artists, are a series of photos – most of which taken on phone – from Bulgarian DJ legend DJ Valentine. Alongside the music it consolidates a label that for the first time will distill some of that Bulgarian traditions into a contemporary platform.

The first release on the label came via KiNK, with the aptly titled “Home,” and in that record we find similarities to KiNK’s music from “Under Destruction” as tracks play on similar rhythmic and melodic themes, distilled down from traditional music, with titles like The Clock and The Grid redefining the concepts contained in their titles for western ears. Accompanying the release and future releases from a small, but dedicated community of artists, are a series of photos – most of which taken on phone – from Bulgarian DJ legend DJ Valentine. Alongside the music it consolidates a label that for the first time will distill some of that Bulgarian traditions into a contemporary platform.

They had known they “had something by the first record” , the rather wordy “some, but not all Cheese comes from the moon.” That record, released on Planet Noise in 2004 had put Ost & Kjex on the map in Norway, but it was when they “sent the first tracks to Crosstown Rebels and they called back” they had something special according to Petter. “When Crosstown Rebels called up, we knew the outside world was listening” reiterates Tore and by the time of Cajun Lunch their sound was truly established.

They had known they “had something by the first record” , the rather wordy “some, but not all Cheese comes from the moon.” That record, released on Planet Noise in 2004 had put Ost & Kjex on the map in Norway, but it was when they “sent the first tracks to Crosstown Rebels and they called back” they had something special according to Petter. “When Crosstown Rebels called up, we knew the outside world was listening” reiterates Tore and by the time of Cajun Lunch their sound was truly established.

Do you remember a specific moment or track that inspired you to first mix two songs together?

Do you remember a specific moment or track that inspired you to first mix two songs together?

Tell me about going to the Loft.

Tell me about going to the Loft. Did he just play on Blå’s soundsystem?

Did he just play on Blå’s soundsystem? Did you ever talk to him about the peak era of the Loft?

Did you ever talk to him about the peak era of the Loft?

She gives my a side glance before answering; “Obviously there is a correlation… do I need to follow that…. A bit if I want to, but not really.” It’s understandable why she won’t acquiesce to the archetypes that dominate DJ culture today. As she insists, she

She gives my a side glance before answering; “Obviously there is a correlation… do I need to follow that…. A bit if I want to, but not really.” It’s understandable why she won’t acquiesce to the archetypes that dominate DJ culture today. As she insists, she

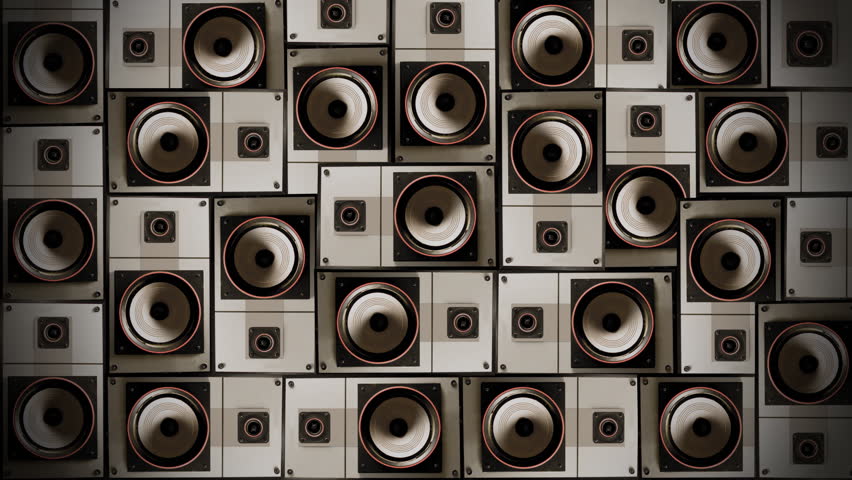

That was my introduction to Jaeger’s “Diskon sound” as I came to know it and throughout my tenure here, the sound system kept growing, shrinking and moving in a constant evolution that owner and resident Ola Smith-Simonsen (Olanskii) still refers to as a ”work in progress.” It’s been in a constant state of flux that has taken a life of its own as the venue, the DJs and the audience kept changing around it and as it kept retreating further into the structural makeup of the room and the dance floor it’s allure is indistinguishable between these elements. And as Ola starts talking about the next phase of the system and the recently-installed bass traps settle into the walls, it’s an evolution in sound that refuses to come to any natural conclusion.

That was my introduction to Jaeger’s “Diskon sound” as I came to know it and throughout my tenure here, the sound system kept growing, shrinking and moving in a constant evolution that owner and resident Ola Smith-Simonsen (Olanskii) still refers to as a ”work in progress.” It’s been in a constant state of flux that has taken a life of its own as the venue, the DJs and the audience kept changing around it and as it kept retreating further into the structural makeup of the room and the dance floor it’s allure is indistinguishable between these elements. And as Ola starts talking about the next phase of the system and the recently-installed bass traps settle into the walls, it’s an evolution in sound that refuses to come to any natural conclusion.

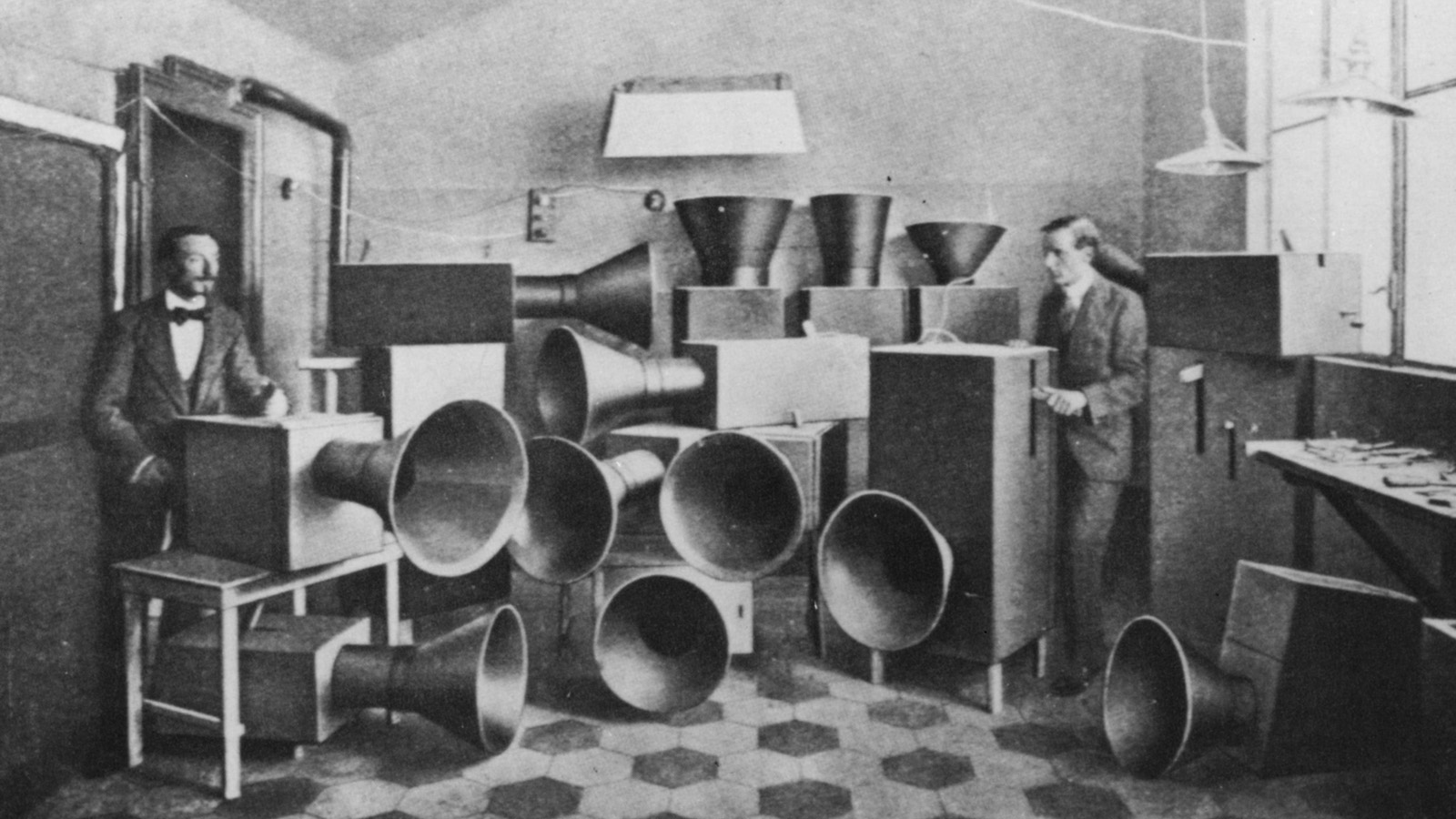

“It’s like money,” collates Rosner in a RBMA lecture; ”you can never have too much because you know you can give some of it away. Loudspeakers can never be too big, because you can always turn the volume down.” In one of Rosner and Mancuso’s crowning achievements at the Loft their combined efforts resulted in creating a tweeter-array system that helped spread those higher sonic frequencies more evenly and further across the room, so that even the person sitting in the back could hear every element in the music rather than just the bass frequencies, which naturally has the longest reach. Even though Rosner didn’t initially agree with Mancuso’s tweeter array idea, he soon came around when he discerned ”the more you have up there the better.” It’s a sonic philosophy that’s still noticeably adopted today when you see towers of horns jutting out high above the DJ somewhere like stalagmites on a cave wall, but while it’s certainly helpful having all that sound on tap, it’s pretty pointless if it’s not pointed in the right direction.

“It’s like money,” collates Rosner in a RBMA lecture; ”you can never have too much because you know you can give some of it away. Loudspeakers can never be too big, because you can always turn the volume down.” In one of Rosner and Mancuso’s crowning achievements at the Loft their combined efforts resulted in creating a tweeter-array system that helped spread those higher sonic frequencies more evenly and further across the room, so that even the person sitting in the back could hear every element in the music rather than just the bass frequencies, which naturally has the longest reach. Even though Rosner didn’t initially agree with Mancuso’s tweeter array idea, he soon came around when he discerned ”the more you have up there the better.” It’s a sonic philosophy that’s still noticeably adopted today when you see towers of horns jutting out high above the DJ somewhere like stalagmites on a cave wall, but while it’s certainly helpful having all that sound on tap, it’s pretty pointless if it’s not pointed in the right direction. It was Alex Rosner that introduced Long to this world, as a kind of fixer for his sound systems and it would be Rosner that would also inadvertently put him into business. In “Last night a DJ saved my life,” Francis Grasso described an incident where Rosner sent Long out on a job, and Long usurped his boss by outbidding him on the same job as an independent contractor. Rosner remembers it differently in the RBMA documentary. According to Rosner, John Addison (Studio 54) had phoned Rosner up in the middle of the night to ask about doing some work for him. Rosner swiftly hung up on Addison, noting the lateness of the call in what I assume was short conversation littered with expletives. Addison in all his ‘70s cocaine-fuelled cock-sured fury was not a person you would hang the receiver up on likely and put his next call in to Rosner’s budding apprentice effectively putting Richard Long and associates into business.

It was Alex Rosner that introduced Long to this world, as a kind of fixer for his sound systems and it would be Rosner that would also inadvertently put him into business. In “Last night a DJ saved my life,” Francis Grasso described an incident where Rosner sent Long out on a job, and Long usurped his boss by outbidding him on the same job as an independent contractor. Rosner remembers it differently in the RBMA documentary. According to Rosner, John Addison (Studio 54) had phoned Rosner up in the middle of the night to ask about doing some work for him. Rosner swiftly hung up on Addison, noting the lateness of the call in what I assume was short conversation littered with expletives. Addison in all his ‘70s cocaine-fuelled cock-sured fury was not a person you would hang the receiver up on likely and put his next call in to Rosner’s budding apprentice effectively putting Richard Long and associates into business.

“Drugs, nothing more,” says Tornike, but “when they raided the club, no-one was arrested for dealing drugs and they couldn’t find any drug dealers inside the club, only finding 2 or 3 grams” on individuals. The club owners were arrested too, without a warrant on some overblown claims of obstruction, which never resulted in any charges brought forward, but what happened directly after the raid, was a force of solidarity in a clubbing community that we haven’t seen since the time of the criminal justice and public order act. People like Tornike, who had started gathering outside Bassiani as the police were carting off their friends and colleagues, were protesting the arrests. “We were trying to figure out what was happening,” explains Tornike who “didn’t even know which Police station they took them to” at the time.

“Drugs, nothing more,” says Tornike, but “when they raided the club, no-one was arrested for dealing drugs and they couldn’t find any drug dealers inside the club, only finding 2 or 3 grams” on individuals. The club owners were arrested too, without a warrant on some overblown claims of obstruction, which never resulted in any charges brought forward, but what happened directly after the raid, was a force of solidarity in a clubbing community that we haven’t seen since the time of the criminal justice and public order act. People like Tornike, who had started gathering outside Bassiani as the police were carting off their friends and colleagues, were protesting the arrests. “We were trying to figure out what was happening,” explains Tornike who “didn’t even know which Police station they took them to” at the time.

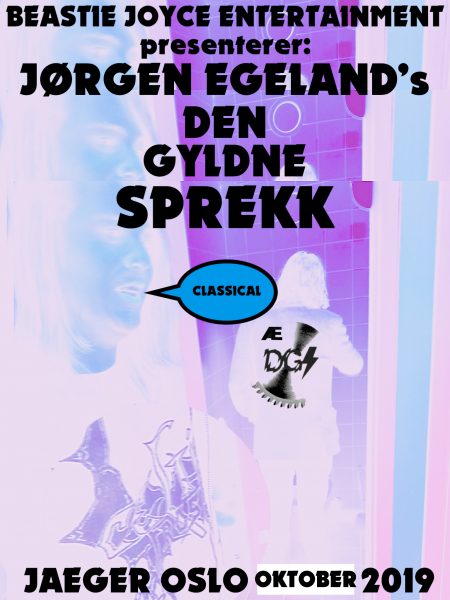

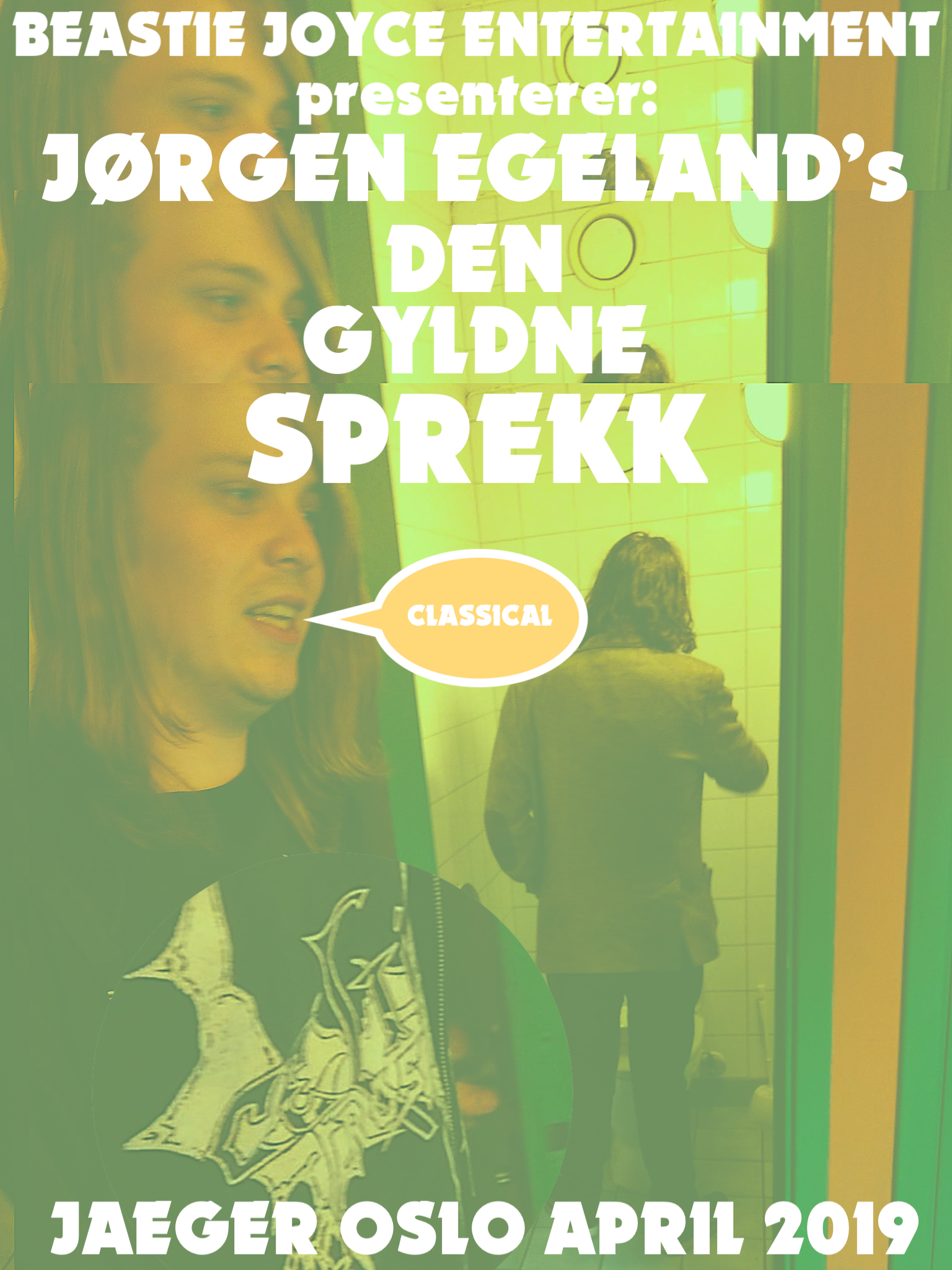

In the month of October, DJ Lekkerman hands over the reigns of his weekly residency to a couple of stalwarts on Den Gyldne Sprekk roster, and two DJs and music enthusiasts that know the concept inside out. Beastie Joyce and Jørgen Egeland host another month of Den Gyldne Sprekk at Jaeger with a series of concepts that go from another KIZZ pøb to the blood-curdling sounds of Memphis Rap for Halloween as the pair resurrect their Funk Boys alias to invite a host of kindred spirits to the lineup for October.

In the month of October, DJ Lekkerman hands over the reigns of his weekly residency to a couple of stalwarts on Den Gyldne Sprekk roster, and two DJs and music enthusiasts that know the concept inside out. Beastie Joyce and Jørgen Egeland host another month of Den Gyldne Sprekk at Jaeger with a series of concepts that go from another KIZZ pøb to the blood-curdling sounds of Memphis Rap for Halloween as the pair resurrect their Funk Boys alias to invite a host of kindred spirits to the lineup for October.  KIZZ PØB returns! What is it about the band in your opinion that continues to draw old and new fans to their music?

KIZZ PØB returns! What is it about the band in your opinion that continues to draw old and new fans to their music?

How did you feel your set at Jaeger went?

How did you feel your set at Jaeger went? Do you consider yourself a veteran of the scene in that respect?

Do you consider yourself a veteran of the scene in that respect?

The music you guys make on Rebound to me sounds like its all built on a foundation of House, but there’s also that frosty Norwegian sonic element in there. What conscious steps do you take in creating that sound?

The music you guys make on Rebound to me sounds like its all built on a foundation of House, but there’s also that frosty Norwegian sonic element in there. What conscious steps do you take in creating that sound?

I spoke to Carl Craig recently and he told me that DJing was the day job to afford the passion of making music. But I have a sneaking suspicion that’s the other way around for you, that DJing is the true passion?

I spoke to Carl Craig recently and he told me that DJing was the day job to afford the passion of making music. But I have a sneaking suspicion that’s the other way around for you, that DJing is the true passion?

I think it would’ve been that way. I know DJs who just don’t have the attention span to make music. Some guys from Detroit I would really like to see out here, more. They are excellent DJs, but just don’t get the opportunity because they don’t have the patience to sit around and programme music.

I think it would’ve been that way. I know DJs who just don’t have the attention span to make music. Some guys from Detroit I would really like to see out here, more. They are excellent DJs, but just don’t get the opportunity because they don’t have the patience to sit around and programme music.

Jann Dahle started making music in 1992 in Tromsø when he moved there to study law. It was a fortuitous time to be making music in Tromsø as the critical point for a burgeoning Disco and House scene that would eventually spread around the globe. “I met Rune (Linbæk), Bjørn (Torske) and Kolbjørn (Lyslo aka Doc L Junior) and I started professionally DJing back then,” remembers Dahle. “There was a lot of buzz about Norwegian Disco at that moment, because of Bjørn,” but Tromsø being a small city, Dahle “got to know everybody” involved in music and landed a job at Brygge Radio alongside Bjørn, Rune, and Geir Jenssen (aka Biosphere).

Jann Dahle started making music in 1992 in Tromsø when he moved there to study law. It was a fortuitous time to be making music in Tromsø as the critical point for a burgeoning Disco and House scene that would eventually spread around the globe. “I met Rune (Linbæk), Bjørn (Torske) and Kolbjørn (Lyslo aka Doc L Junior) and I started professionally DJing back then,” remembers Dahle. “There was a lot of buzz about Norwegian Disco at that moment, because of Bjørn,” but Tromsø being a small city, Dahle “got to know everybody” involved in music and landed a job at Brygge Radio alongside Bjørn, Rune, and Geir Jenssen (aka Biosphere).

When and how did Techno exactly come into your life and what drew you to the genre?

When and how did Techno exactly come into your life and what drew you to the genre? What do you look for in a Techno track to make it into your sets?

What do you look for in a Techno track to make it into your sets?

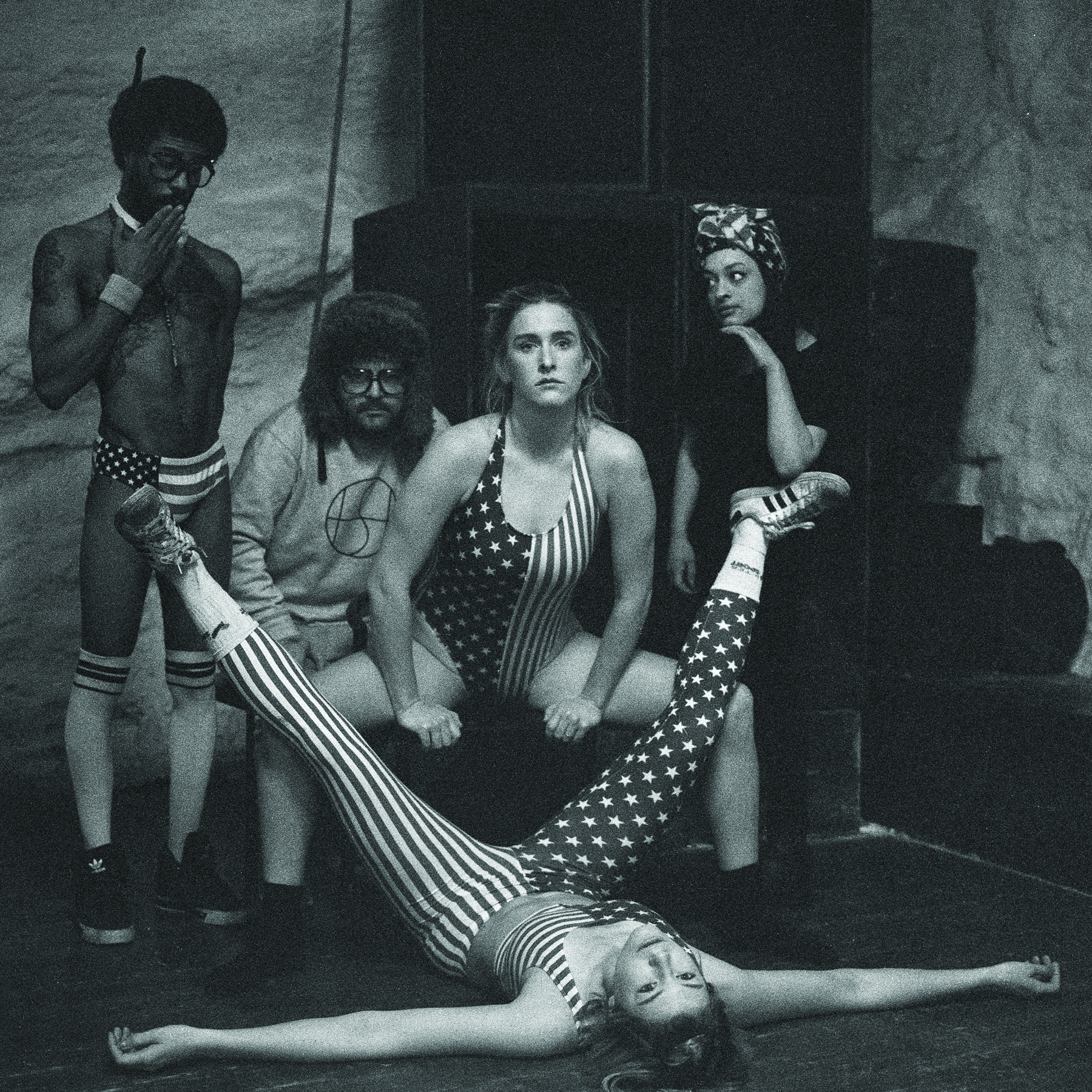

Channeling that experience of touring and playing live into this record, Dave Harrington Group favour an uninhibited approach on “Pure Imagination, No Country” as they capture that raw intensity and power of a live band in the studio. Nick Murphy emphasises this energy through post production, which on their previous LP, favoured a slicker, more refined approach. Dave Harrington’s guitar takes more of a central role on the LP, where it appears mostly unprocessed in its natural state taking the stage front and centre in the production across the album.

Channeling that experience of touring and playing live into this record, Dave Harrington Group favour an uninhibited approach on “Pure Imagination, No Country” as they capture that raw intensity and power of a live band in the studio. Nick Murphy emphasises this energy through post production, which on their previous LP, favoured a slicker, more refined approach. Dave Harrington’s guitar takes more of a central role on the LP, where it appears mostly unprocessed in its natural state taking the stage front and centre in the production across the album.

Working with TB Arthur and people like BMG, do you think It’s changed the way you make music?

Working with TB Arthur and people like BMG, do you think It’s changed the way you make music? Like every DJ out there today you have an agent that takes care of your bookings, but do you have the final say where you’ll play?

Like every DJ out there today you have an agent that takes care of your bookings, but do you have the final say where you’ll play?

Why these particular remix artists?

Why these particular remix artists?

I’ve read that your philosophy is about exporting the Black Motion, and in extension the South African sound to the wider world.

I’ve read that your philosophy is about exporting the Black Motion, and in extension the South African sound to the wider world.

“It’s really simple,” he explains. Some of his “family lives in Hamburg” and he would often visit them there. He became familiar with the label through the music of Kasper Bjørke and sent them the demo for “To Grieve”. Two weeks later HFN answered “yes, it’s cool, we want to release it,” but y then the idea of an album had started to take shape, and Karol would only give them the single if they released the album. The acquiesced and “Truth” was born.

“It’s really simple,” he explains. Some of his “family lives in Hamburg” and he would often visit them there. He became familiar with the label through the music of Kasper Bjørke and sent them the demo for “To Grieve”. Two weeks later HFN answered “yes, it’s cool, we want to release it,” but y then the idea of an album had started to take shape, and Karol would only give them the single if they released the album. The acquiesced and “Truth” was born.

The idea of dugnadsånden is also how Ra-Shidi had her start as a DJ. “I just went up to the manager at Circa and asked if I could play there, and he just said, ‘yeah sure’.” Unfortunately, Circa is coming to an end in two months, and Ra-Shidi is hoping Storgata Camping will carry the beacon for the clubbing community, with more reserved bookings but with a bigger impact to attract the larger audience to fill the dance floor.

The idea of dugnadsånden is also how Ra-Shidi had her start as a DJ. “I just went up to the manager at Circa and asked if I could play there, and he just said, ‘yeah sure’.” Unfortunately, Circa is coming to an end in two months, and Ra-Shidi is hoping Storgata Camping will carry the beacon for the clubbing community, with more reserved bookings but with a bigger impact to attract the larger audience to fill the dance floor.

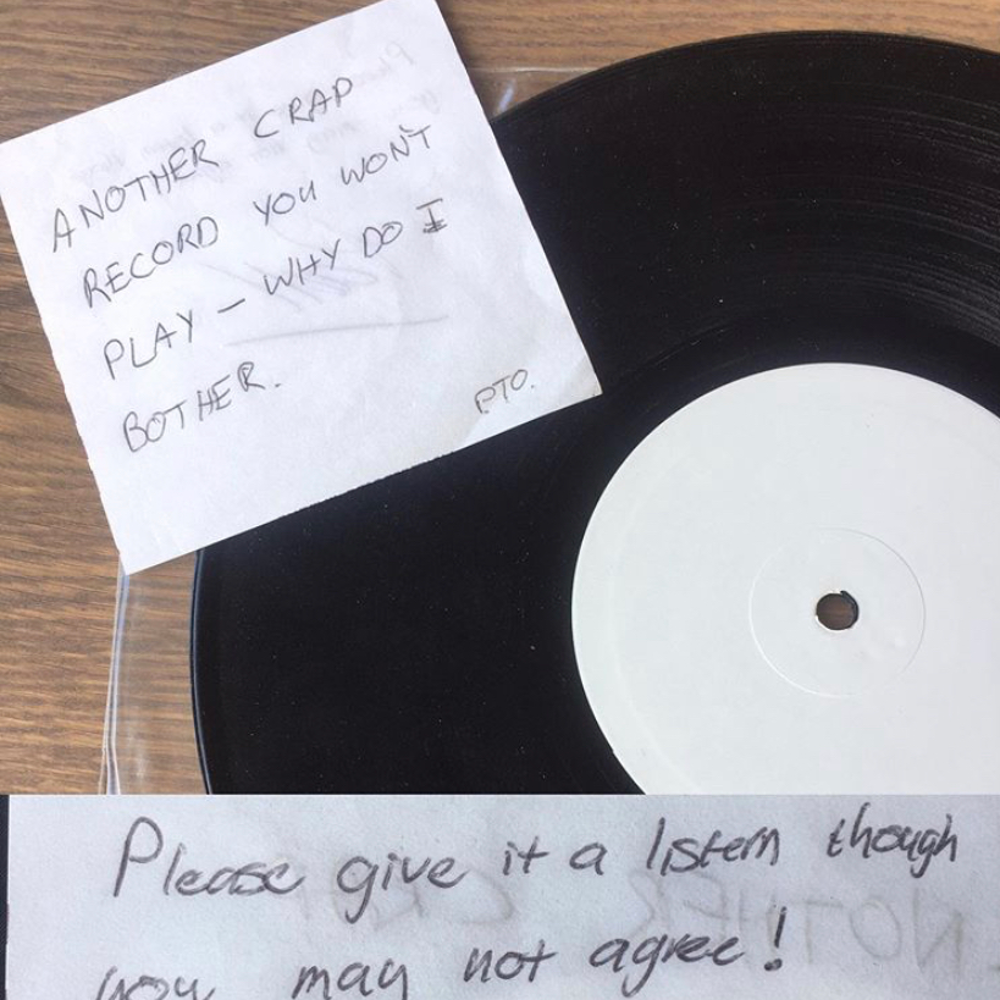

We just can’t get too much of a good thing, and while many of us are still reeling from Mr. G performance in Jæger’s basement from last Friday, Filter Musikk sneaked in a copy of That Cold Sweat EP to keep the momentum going. It’s a limited release produced specifically for record store day and if you were in our basement, you might remember one or two tracks from his set.

We just can’t get too much of a good thing, and while many of us are still reeling from Mr. G performance in Jæger’s basement from last Friday, Filter Musikk sneaked in a copy of That Cold Sweat EP to keep the momentum going. It’s a limited release produced specifically for record store day and if you were in our basement, you might remember one or two tracks from his set.

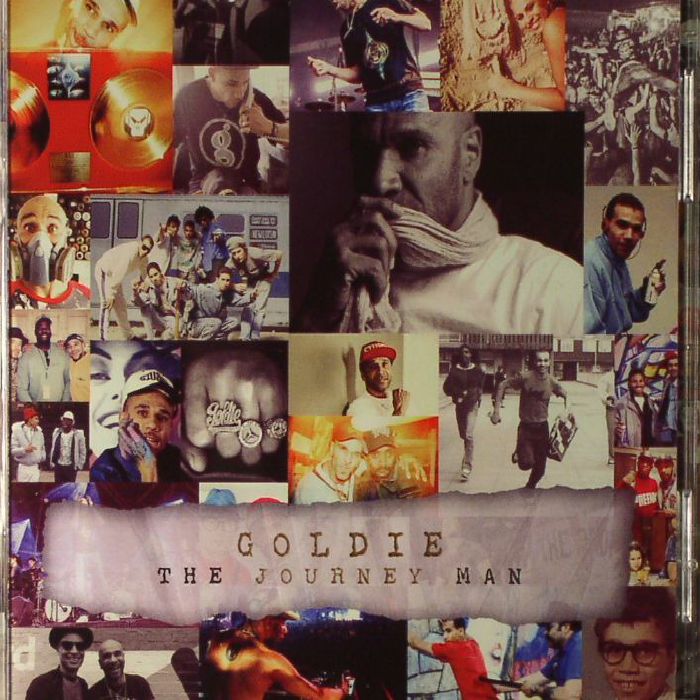

Drum and Bass producers make great music, no doubt. DnB might the genre they are known for, but loads of the artists also make supercharged beats that carry on that vibe of the genre, but at a more reserved pace. Drum and Bass is a genre that co-opted the technology back in the 90s in the UK and the result was a whole new style of music that paved the way for much of today’s electronic music, beyond that singular genre. Think IDM, hardcore, dubstep, Techno… no…Yes. Drum and Bass is everywhere, you here an amen break or a saw tooth wave bass, and one label in partcular has played a significant part in spreading that gospel, Metalheadz.

Drum and Bass producers make great music, no doubt. DnB might the genre they are known for, but loads of the artists also make supercharged beats that carry on that vibe of the genre, but at a more reserved pace. Drum and Bass is a genre that co-opted the technology back in the 90s in the UK and the result was a whole new style of music that paved the way for much of today’s electronic music, beyond that singular genre. Think IDM, hardcore, dubstep, Techno… no…Yes. Drum and Bass is everywhere, you here an amen break or a saw tooth wave bass, and one label in partcular has played a significant part in spreading that gospel, Metalheadz.

The way you explained it was that the shop, Afro Synth is very much a labour of love for you. Can you tell me a bit more about what inspired you to start and run the shop?

The way you explained it was that the shop, Afro Synth is very much a labour of love for you. Can you tell me a bit more about what inspired you to start and run the shop?

The origins of Techno

The origins of Techno

That all changed with the New Jackson / Elliot Lion split, Cin Cin 006. The label achieved a visual identity with that release that extends up to the most recent release, Cin Cin 010. Featuring artwork from Arnau Bi Ponany, the look of the label was largely influenced by Greene’s tastes and his admiration for the aesthetic of labels like Whities and Live at Robert Johnson according to an exchange between Tillett and Greene on Thump.

That all changed with the New Jackson / Elliot Lion split, Cin Cin 006. The label achieved a visual identity with that release that extends up to the most recent release, Cin Cin 010. Featuring artwork from Arnau Bi Ponany, the look of the label was largely influenced by Greene’s tastes and his admiration for the aesthetic of labels like Whities and Live at Robert Johnson according to an exchange between Tillett and Greene on Thump.

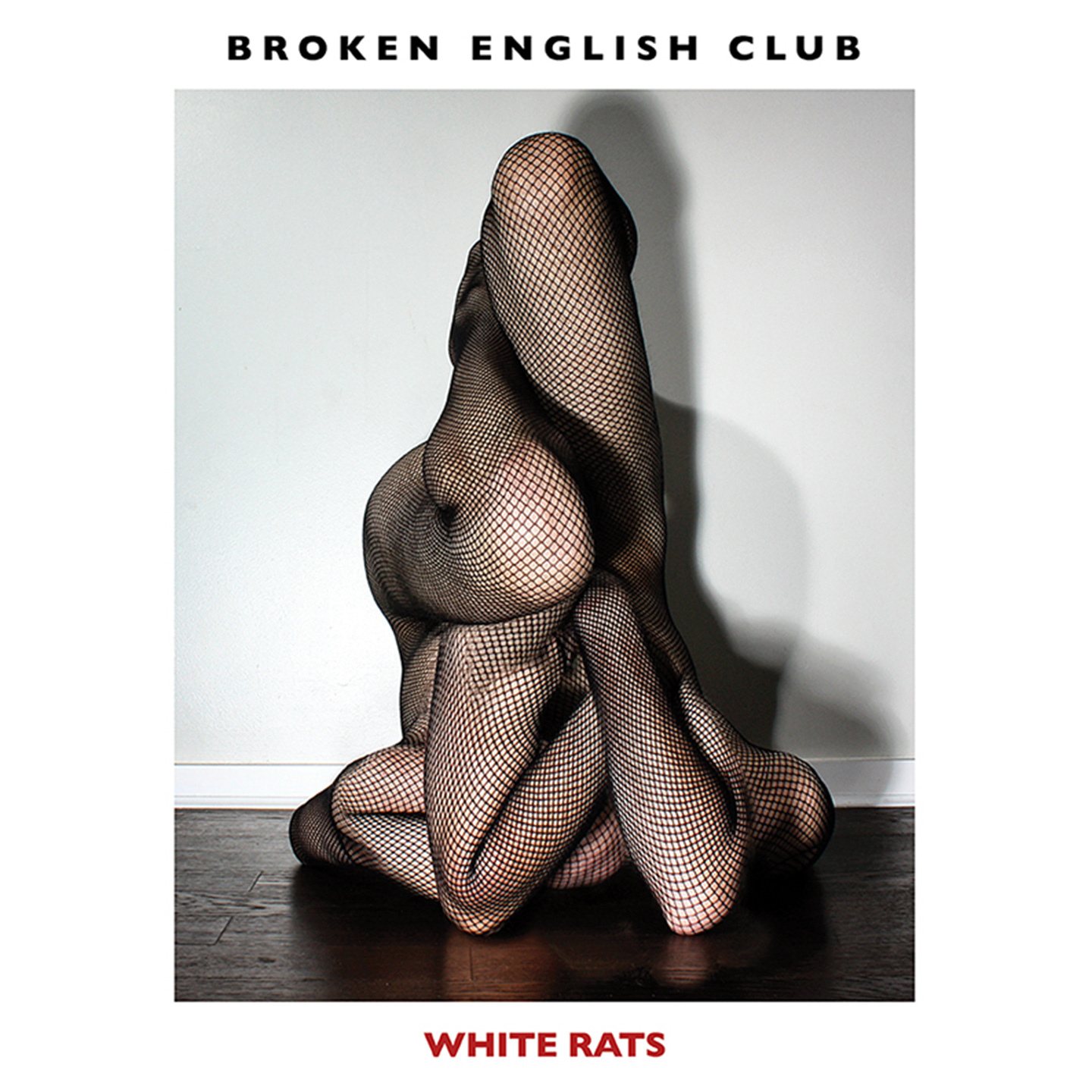

Issue no. sixteen with Broken English Club (Oliver Ho) comes to mind. Ho’s known obsession with JG Ballard and especially the novel Crash is brought to real life through the photograph on the cover. A human torso at the wheel of a car takes on the form of a mannequin (perhaps a reference to Mannequin records) in a flesh-body suit that compliments to blue hue of the automobile interior perfectly. “I wanted to embody that, mix it up a bit,” he explained in Resident Advisor. “Something like Eyes Without Face meets Crash.” He continues: “I wanted it to have this androgynous, non-sexual feeling. That’s why I used the tin body suit with medical braces. I wanted to push my design off the table top.”

Issue no. sixteen with Broken English Club (Oliver Ho) comes to mind. Ho’s known obsession with JG Ballard and especially the novel Crash is brought to real life through the photograph on the cover. A human torso at the wheel of a car takes on the form of a mannequin (perhaps a reference to Mannequin records) in a flesh-body suit that compliments to blue hue of the automobile interior perfectly. “I wanted to embody that, mix it up a bit,” he explained in Resident Advisor. “Something like Eyes Without Face meets Crash.” He continues: “I wanted it to have this androgynous, non-sexual feeling. That’s why I used the tin body suit with medical braces. I wanted to push my design off the table top.”

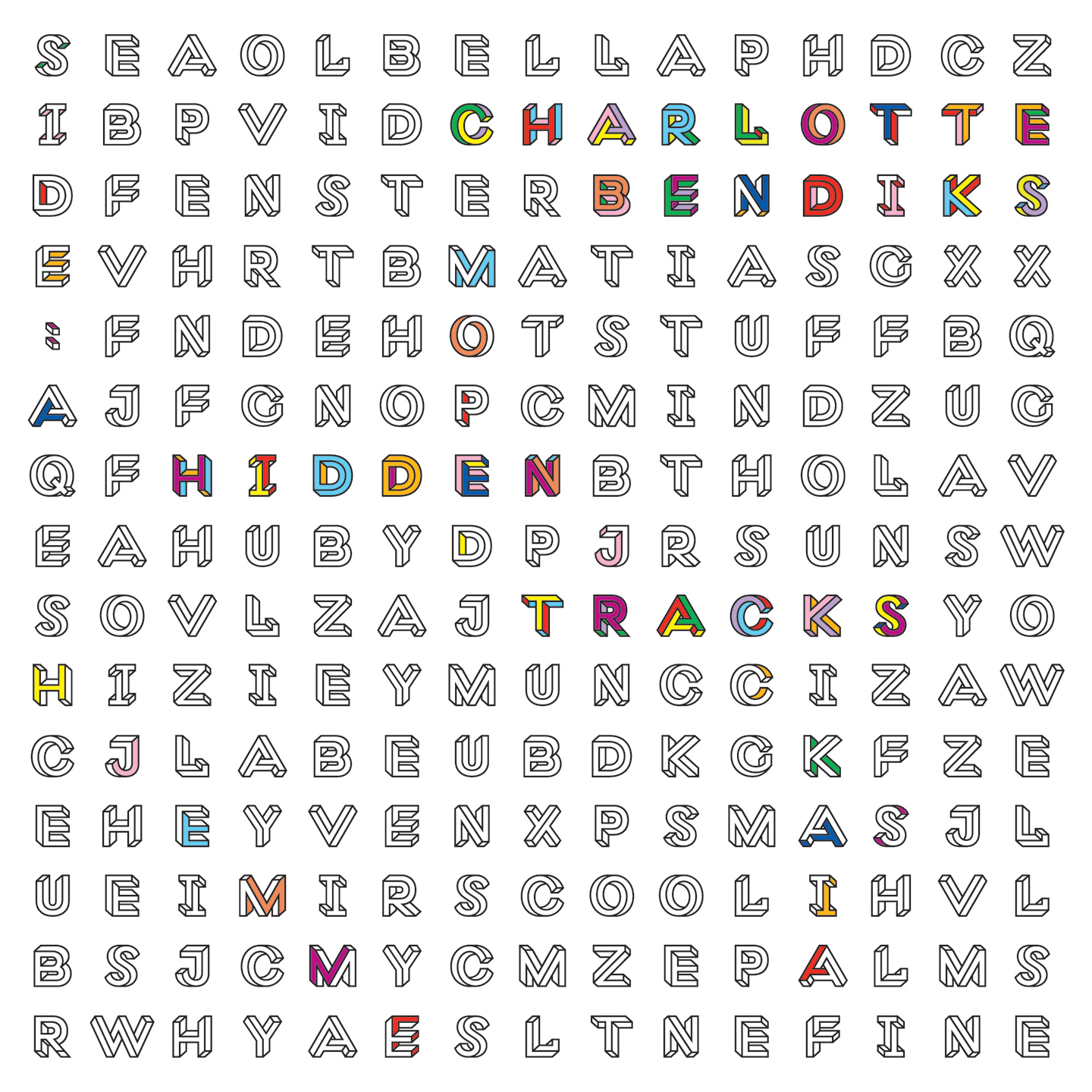

“After DJing for six years, it became pretty obvious to most people that I actually was a woman, not a man”, she told XLR8R. Raving George started to “lose its purpose” and she “didn’t feel the need to hide behind a male alter ego anymore.” A changing landscape in the electronic music world and Raving George’s services were no longer required, with Charlotte de Witte free to make this an eponymous career free of prejudices. “This is who I am; I am a woman, playing and producing music, and I’m bloody well proud of it too.

“After DJing for six years, it became pretty obvious to most people that I actually was a woman, not a man”, she told XLR8R. Raving George started to “lose its purpose” and she “didn’t feel the need to hide behind a male alter ego anymore.” A changing landscape in the electronic music world and Raving George’s services were no longer required, with Charlotte de Witte free to make this an eponymous career free of prejudices. “This is who I am; I am a woman, playing and producing music, and I’m bloody well proud of it too.

Mikrometeorittene’s closest descendant is Mechanized World, but offering a much more contemporary approach to the Techno genre. I wonder if it is down to an evolution in their work, but Truls suggests not. “I feel in a way we go in a circle” and redefining the parameters between the projects has allowed them more freedom to explore these more purest forms of their cavernous electronic music interests. KSMISK is a “different vibe in general” according to Robin who also believes they should’ve separated these different sounds “years ago”.

Mikrometeorittene’s closest descendant is Mechanized World, but offering a much more contemporary approach to the Techno genre. I wonder if it is down to an evolution in their work, but Truls suggests not. “I feel in a way we go in a circle” and redefining the parameters between the projects has allowed them more freedom to explore these more purest forms of their cavernous electronic music interests. KSMISK is a “different vibe in general” according to Robin who also believes they should’ve separated these different sounds “years ago”.

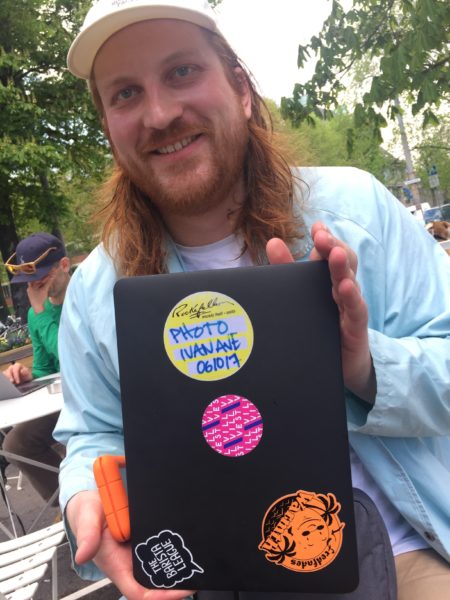

Olav packs his computer away. The pristine cover is a mesh of colourful stickers, hinting in no subtle way to his affiliation with the Mutual Intentions crew.

Olav packs his computer away. The pristine cover is a mesh of colourful stickers, hinting in no subtle way to his affiliation with the Mutual Intentions crew.

Fredrik didn’t go straight from metal to Techno however, but drumming played an integral role in th DJ prowess he displayed early on. Fredrik’s acute ear for rhythm took to DJing very naturally and as a tram goes by in the background by way of serendipitous illumination, Fredrik explains; “I can hear the tram go by and I can immediately feel the rhythm.” He “always knew what DJing was about” because of his older brothers and when he turned 18 and “started partying” DJing came from Fredrik’s desire “to perform music”. He bought “some cheap decks” and through a period of “listening to commercial, shit music” started DJing.

Fredrik didn’t go straight from metal to Techno however, but drumming played an integral role in th DJ prowess he displayed early on. Fredrik’s acute ear for rhythm took to DJing very naturally and as a tram goes by in the background by way of serendipitous illumination, Fredrik explains; “I can hear the tram go by and I can immediately feel the rhythm.” He “always knew what DJing was about” because of his older brothers and when he turned 18 and “started partying” DJing came from Fredrik’s desire “to perform music”. He bought “some cheap decks” and through a period of “listening to commercial, shit music” started DJing.

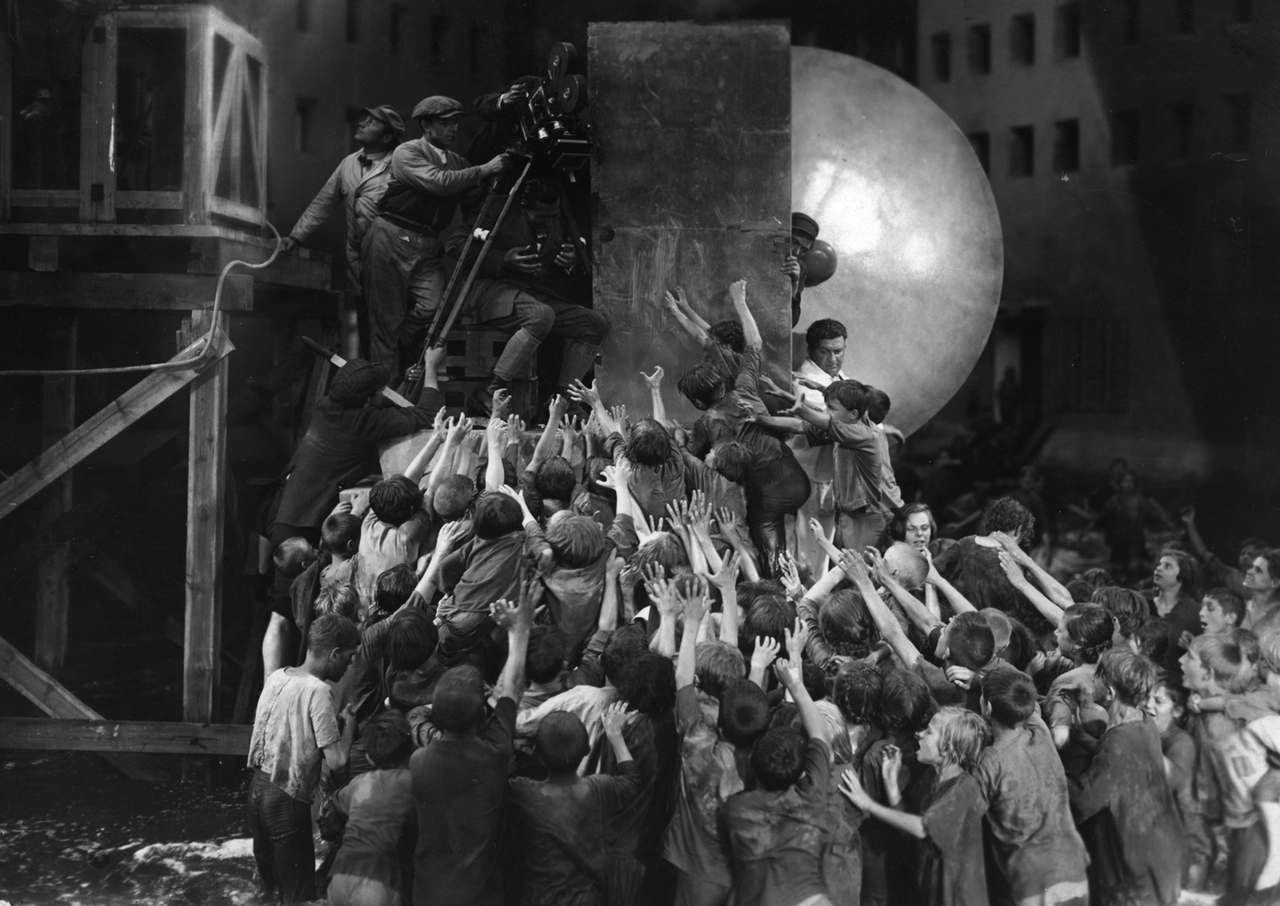

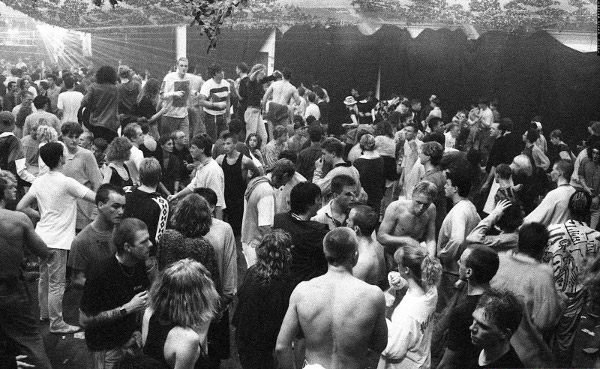

Later that evening after our interview the energy is electric in Jæger’s backyard, peaking at excessive levels, and then suddenly a drop in the bottom end. A wispy melody of some unknown origins builds tension and the whole crowd lurches forward, towards the booth as one. There’s a moment of inextricable pause… it’s nearly silent… and then an exhilarated whoop from the audience as the bass and drums kick back in to the pulse of the dance floor.

Later that evening after our interview the energy is electric in Jæger’s backyard, peaking at excessive levels, and then suddenly a drop in the bottom end. A wispy melody of some unknown origins builds tension and the whole crowd lurches forward, towards the booth as one. There’s a moment of inextricable pause… it’s nearly silent… and then an exhilarated whoop from the audience as the bass and drums kick back in to the pulse of the dance floor.

It seems however that opinion is divided between a high profile DJ like Thaemlitz and the DJs that still work at a local, subcultural level. While a DJ like Thaemlitz is openly opposed to mixed spaces as it heteronormalises the queer aspects of the culture, a younger generation of DJs like Terje Dybdahl and Timothy Wang are embracing and indeed welcoming the mixed orientation of the audiences. As more previously rigidly queer spaces and events like Kaos, overwhelmingly welcome mixed audiences, albeit retaining their queer identity, it appears that a mixed philosophy is becoming the acceptable norm. My first thought was that this might be predicated on a regional aspect since in Europe and the UK this music and its culture was first adopted by a heterosexual audience, but this doesn’t really concur with what US DJ Jason Kendig from Honey Soundsystem told me last year during an interview for Jæger’s blog. He put emphasis on the fact that he and the soundsystem’s “first experiences in dance music were not necessarily in queer spaces”.

It seems however that opinion is divided between a high profile DJ like Thaemlitz and the DJs that still work at a local, subcultural level. While a DJ like Thaemlitz is openly opposed to mixed spaces as it heteronormalises the queer aspects of the culture, a younger generation of DJs like Terje Dybdahl and Timothy Wang are embracing and indeed welcoming the mixed orientation of the audiences. As more previously rigidly queer spaces and events like Kaos, overwhelmingly welcome mixed audiences, albeit retaining their queer identity, it appears that a mixed philosophy is becoming the acceptable norm. My first thought was that this might be predicated on a regional aspect since in Europe and the UK this music and its culture was first adopted by a heterosexual audience, but this doesn’t really concur with what US DJ Jason Kendig from Honey Soundsystem told me last year during an interview for Jæger’s blog. He put emphasis on the fact that he and the soundsystem’s “first experiences in dance music were not necessarily in queer spaces”.

Behind every good DJ is that urge to dig deeper and further, and in Christopher it manifested into an obsessive-compulsive habit when a couple of Joey Negro compilations came his way. “A lot of the House music I listened to came from these tracks” explains Christopher and what started in House music moved into Disco, Soul and Boogie’s more obscure corners. “When I hear a sample that I know from somewhere I get totally obsessed about finding it“, says Christopher. The DJ turned collector after a digging session in Berlin. Stumbling on the originals of some of his “favourite” House tracks, Christopher started exploring the outlying regions of Disco through his sets. “Felix (Klein) did exactly the same thing at the same time” and the two DJs “hooked up and started playing Soul, Disco and Boogie together.” Driven by his desire to find the original of a sample from a House track, and looking beyond the obvious, Christopher “started spending all (his) money on records” and Disco lead to Boogie and of course eventually Boogienetter… but first there was Diskotaket.

Behind every good DJ is that urge to dig deeper and further, and in Christopher it manifested into an obsessive-compulsive habit when a couple of Joey Negro compilations came his way. “A lot of the House music I listened to came from these tracks” explains Christopher and what started in House music moved into Disco, Soul and Boogie’s more obscure corners. “When I hear a sample that I know from somewhere I get totally obsessed about finding it“, says Christopher. The DJ turned collector after a digging session in Berlin. Stumbling on the originals of some of his “favourite” House tracks, Christopher started exploring the outlying regions of Disco through his sets. “Felix (Klein) did exactly the same thing at the same time” and the two DJs “hooked up and started playing Soul, Disco and Boogie together.” Driven by his desire to find the original of a sample from a House track, and looking beyond the obvious, Christopher “started spending all (his) money on records” and Disco lead to Boogie and of course eventually Boogienetter… but first there was Diskotaket.

Give us an introduction

Give us an introduction

Meanwhile, even at the core, we in the First World internalize a slave ethic of mandatory participation in labor until old age. There is an insistence that we all “socially contribute” (in terms that dominant culture recognizes as contribution), and an incredible pressure not to “exploit” or rely upon the few social services that are available to us. Those who cannot earn enough to afford living in a First World culture are socially punished, sued, evicted, deported or incarcerated. Those who refuse to work are the most dreaded of all. Non-participation is such a taboo that the majority of us immediately rule it out as a possibility – yet who among us ever asked to be born into this shit world? Again, the sophistication and complexity of this hornet’s nest makes our own slavery appear to be something else. Something distant in time or location, or perhaps even something that has been overcome. This is delusion. And even if one refuses to identify one’s own working ethic as rooted in a model of slavery, any realist should easily be able to list off at least two or three types of unquestionable slavery within their own local economy. Just start by identifying the types of labor available to people without proper legal status or protections. Sex work is an easy one to get the list going… Meanwhile, how many “democracies” continue to have royal families? I believe that is also part of the Nordic Model.

Meanwhile, even at the core, we in the First World internalize a slave ethic of mandatory participation in labor until old age. There is an insistence that we all “socially contribute” (in terms that dominant culture recognizes as contribution), and an incredible pressure not to “exploit” or rely upon the few social services that are available to us. Those who cannot earn enough to afford living in a First World culture are socially punished, sued, evicted, deported or incarcerated. Those who refuse to work are the most dreaded of all. Non-participation is such a taboo that the majority of us immediately rule it out as a possibility – yet who among us ever asked to be born into this shit world? Again, the sophistication and complexity of this hornet’s nest makes our own slavery appear to be something else. Something distant in time or location, or perhaps even something that has been overcome. This is delusion. And even if one refuses to identify one’s own working ethic as rooted in a model of slavery, any realist should easily be able to list off at least two or three types of unquestionable slavery within their own local economy. Just start by identifying the types of labor available to people without proper legal status or protections. Sex work is an easy one to get the list going… Meanwhile, how many “democracies” continue to have royal families? I believe that is also part of the Nordic Model.

I was raised in the US, and immigrated to Japan – both of which are cultures with nearly zero federal funding for art and music. So while I understand the logic of feeling entitled to a share of public funds created by one’s tax payments, I also am never surprised when those funds go to the most conservative cultural elements – like classical music halls, or galleries for housing old paintings. Similarly, I never forget futurism’s role as the official art of fascist Italy, or social realism’s role in totalitarian Chinese and Soviet regimes, etc. So both my sense of history and personal experience keeps me from ever being excited by news of countries that fund artists.

I was raised in the US, and immigrated to Japan – both of which are cultures with nearly zero federal funding for art and music. So while I understand the logic of feeling entitled to a share of public funds created by one’s tax payments, I also am never surprised when those funds go to the most conservative cultural elements – like classical music halls, or galleries for housing old paintings. Similarly, I never forget futurism’s role as the official art of fascist Italy, or social realism’s role in totalitarian Chinese and Soviet regimes, etc. So both my sense of history and personal experience keeps me from ever being excited by news of countries that fund artists.

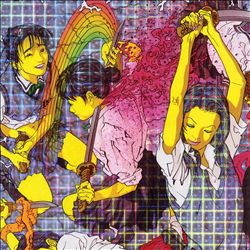

Quarantine made an instant impression on the listener and whether you liked it or loathed it, it was definitely not inadmissible. Critics merely praised it, and accolades for Laurel Halo’s work came in abundance, but public opinion definitely remained divided. “The record’s not meant for everyone”, explained Halo in an interview with the Quietus shortly after the release. “(I)t’s not a pop record in the slightest so I think people expecting that would be disappointed by the vocal tone and production approach.” By the time you get to the second song on the album “Years” you would either be entranced or disenchanted by the beat-less sojourn through Halo’s emotive depths on her debut album. Although Halo’s debut EP, King Felix certainly had ears pricking up everywhere, it would be Quarantine that launched her career, making a vivid statement from the music right through to the artwork, designed by Makota Aira; a colourful and humorous display of Seppuku (ritual Japanese suicide).

Quarantine made an instant impression on the listener and whether you liked it or loathed it, it was definitely not inadmissible. Critics merely praised it, and accolades for Laurel Halo’s work came in abundance, but public opinion definitely remained divided. “The record’s not meant for everyone”, explained Halo in an interview with the Quietus shortly after the release. “(I)t’s not a pop record in the slightest so I think people expecting that would be disappointed by the vocal tone and production approach.” By the time you get to the second song on the album “Years” you would either be entranced or disenchanted by the beat-less sojourn through Halo’s emotive depths on her debut album. Although Halo’s debut EP, King Felix certainly had ears pricking up everywhere, it would be Quarantine that launched her career, making a vivid statement from the music right through to the artwork, designed by Makota Aira; a colourful and humorous display of Seppuku (ritual Japanese suicide).

Hannevold’s moniker undoubtedly takes its name from the transliteration of the Chinese city Taxkorgan, a major stop along the original silk road with an oriental flavour informing the signature sound of this project. Bamboo flutes, oriental scales and plucked strings echo the lost sounds of an age-old culture, transposing them into a modern dialect through electronic means and re-establishing them in an avant-pop context. Merging these oriental flavours with elements of fringe-rock, Taxgorkhan creates a kind of pseudo new-age music without the pretence or irony that’s usually associated with that music.

Hannevold’s moniker undoubtedly takes its name from the transliteration of the Chinese city Taxkorgan, a major stop along the original silk road with an oriental flavour informing the signature sound of this project. Bamboo flutes, oriental scales and plucked strings echo the lost sounds of an age-old culture, transposing them into a modern dialect through electronic means and re-establishing them in an avant-pop context. Merging these oriental flavours with elements of fringe-rock, Taxgorkhan creates a kind of pseudo new-age music without the pretence or irony that’s usually associated with that music.

That was around 2004/5 I guess?

That was around 2004/5 I guess? Roland TR- 909

Roland TR- 909 Oberheim Matrix 12

Oberheim Matrix 12 Roland TB-303

Roland TB-303 Universal Audio Apollo

Universal Audio Apollo A Korg Guy

A Korg Guy

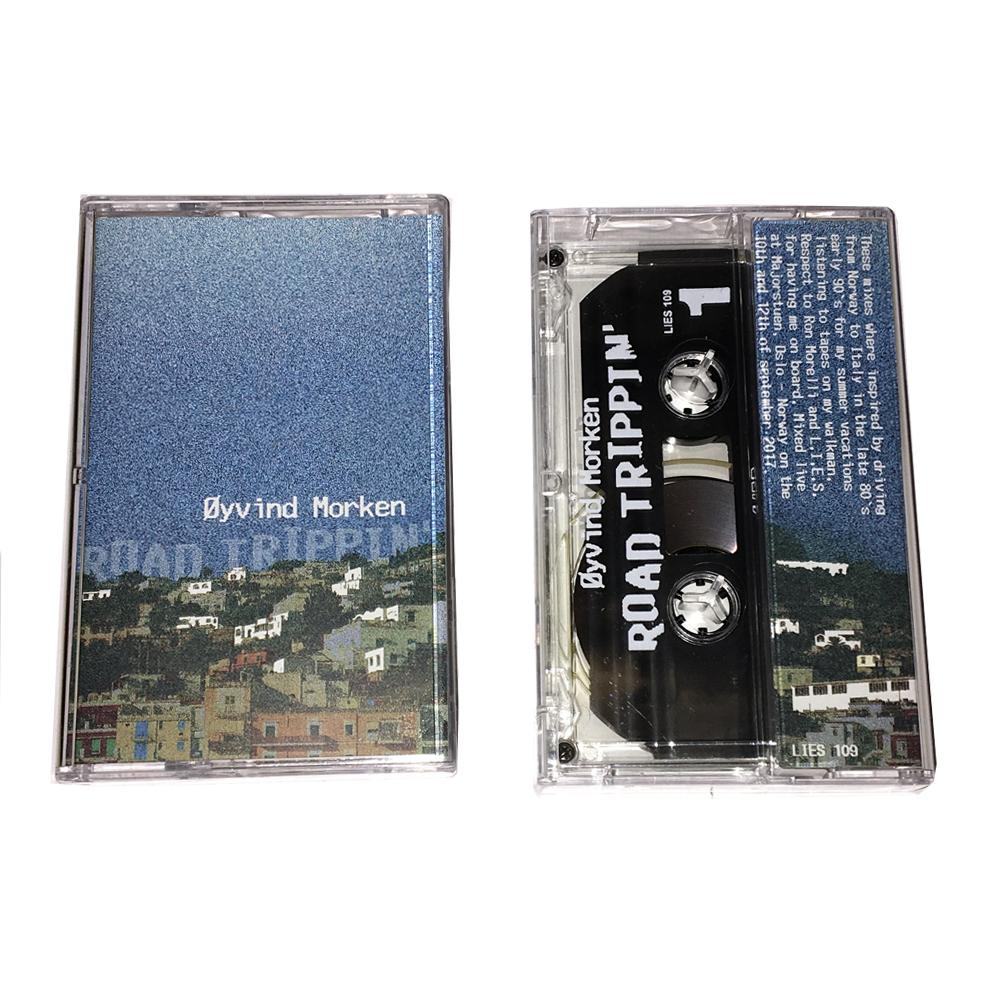

It kind of just happened. I missed working with music, and that was one of the first things I did feel along the trip. I’ve always been heavily interested in making sound recordings. A lot of people that travel, they either blog it or take pictures, and I thought for me, it would be quite natural to make mix tapes of the music we were listening to a lot on the road, and mix it with experiences on the road.

It kind of just happened. I missed working with music, and that was one of the first things I did feel along the trip. I’ve always been heavily interested in making sound recordings. A lot of people that travel, they either blog it or take pictures, and I thought for me, it would be quite natural to make mix tapes of the music we were listening to a lot on the road, and mix it with experiences on the road.  Yes, I’m always collecting music, but it’s not in the way that you think. A lot of people have this romantic idea that I’m going to record stores every week and digging South American gems. First of all it’s not like that at all there, there are not that many record stores there apart from the big cities. I don’t have the space for it and I don’t have a record player on the road. I did consider getting a portable record player, but then I got scared, because half the time you just become a digger instead of travelling and all the other stuff that I enjoy. So I’m just collecting music online.

Yes, I’m always collecting music, but it’s not in the way that you think. A lot of people have this romantic idea that I’m going to record stores every week and digging South American gems. First of all it’s not like that at all there, there are not that many record stores there apart from the big cities. I don’t have the space for it and I don’t have a record player on the road. I did consider getting a portable record player, but then I got scared, because half the time you just become a digger instead of travelling and all the other stuff that I enjoy. So I’m just collecting music online.  You mentioned diversity there and I must admit hew first place I really picked up on an eclecticism in the booth becoming popular was at Trouw. Do you think that was a part of the legacy it left on the DJ scene?

You mentioned diversity there and I must admit hew first place I really picked up on an eclecticism in the booth becoming popular was at Trouw. Do you think that was a part of the legacy it left on the DJ scene?

T

T

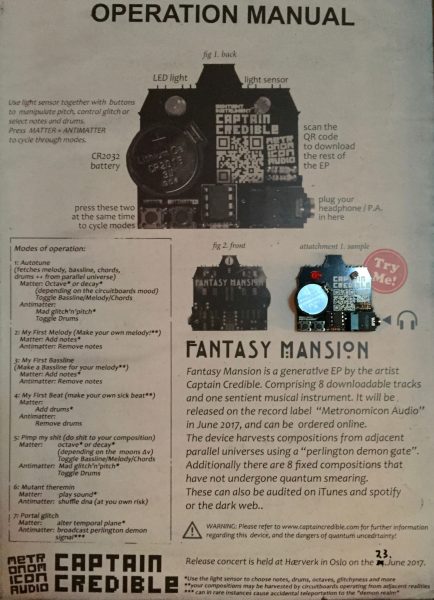

I’ve been playing around on your “EP” at Jæger.

I’ve been playing around on your “EP” at Jæger.

Possibly the first EP to ever be released on PCB, Fantasy Mansion by Captain Credible has been installed Jæger this week for a preview. Part album preview, part art installation, part musical instrument, the album is now up at Jæger for your listening pleasure. Channeling elements of Aphex Twin and Otto Von Schirach, Captain Credible describes his music as “punk-electronica”. At times intense cacophony at other’s serene innocence, Fantasy Mansion is an EP that lives in its own dimension. “The physical manifestation of this EP is a circuit board with buttons, a light sensor and a headphone jack. This circuit board can be played as a musical instrument, and the user can easily compose his or her own melodies. It will also generate its own beats and melodies and even occasionally modify those made by the user. It will also synchronize to external hardware like drum machines or sequencers. This EP is therefore not a finished work, but instead a starting point for further experimentation and expression by the user.” The PCB will be up in our landing leading down to our basement, so bring a set of headphones and experience it for yourself, before it’s official release date on the 16th of June.

Possibly the first EP to ever be released on PCB, Fantasy Mansion by Captain Credible has been installed Jæger this week for a preview. Part album preview, part art installation, part musical instrument, the album is now up at Jæger for your listening pleasure. Channeling elements of Aphex Twin and Otto Von Schirach, Captain Credible describes his music as “punk-electronica”. At times intense cacophony at other’s serene innocence, Fantasy Mansion is an EP that lives in its own dimension. “The physical manifestation of this EP is a circuit board with buttons, a light sensor and a headphone jack. This circuit board can be played as a musical instrument, and the user can easily compose his or her own melodies. It will also generate its own beats and melodies and even occasionally modify those made by the user. It will also synchronize to external hardware like drum machines or sequencers. This EP is therefore not a finished work, but instead a starting point for further experimentation and expression by the user.” The PCB will be up in our landing leading down to our basement, so bring a set of headphones and experience it for yourself, before it’s official release date on the 16th of June.

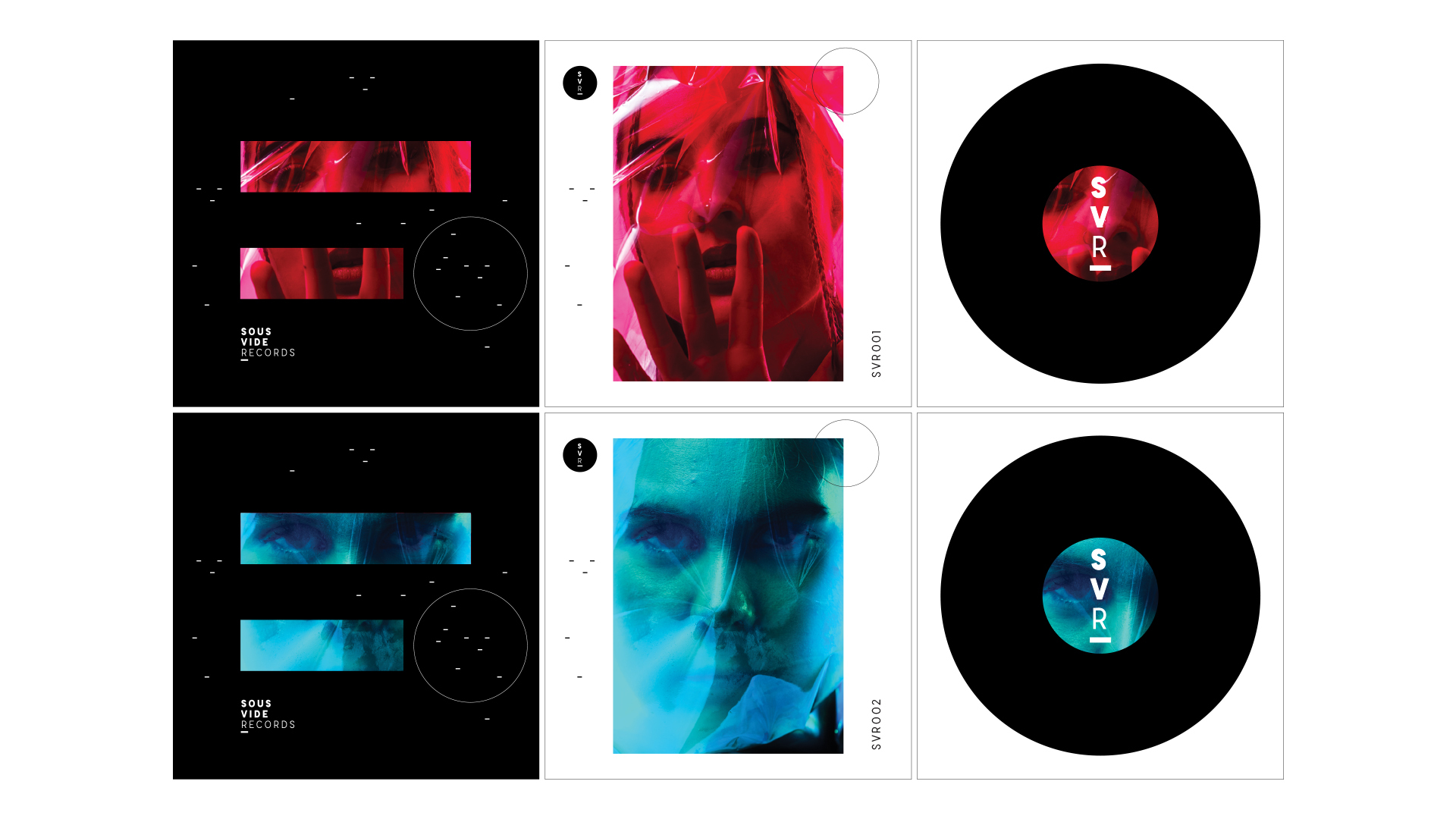

There’s a lot of emphasis on a visual presentation. What do you hope the visual accompaniment brings to the releases away from the music?

There’s a lot of emphasis on a visual presentation. What do you hope the visual accompaniment brings to the releases away from the music?

Karina

Karina

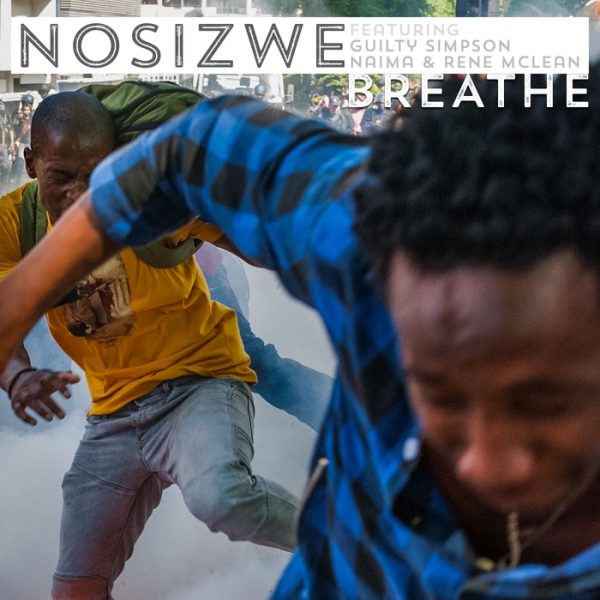

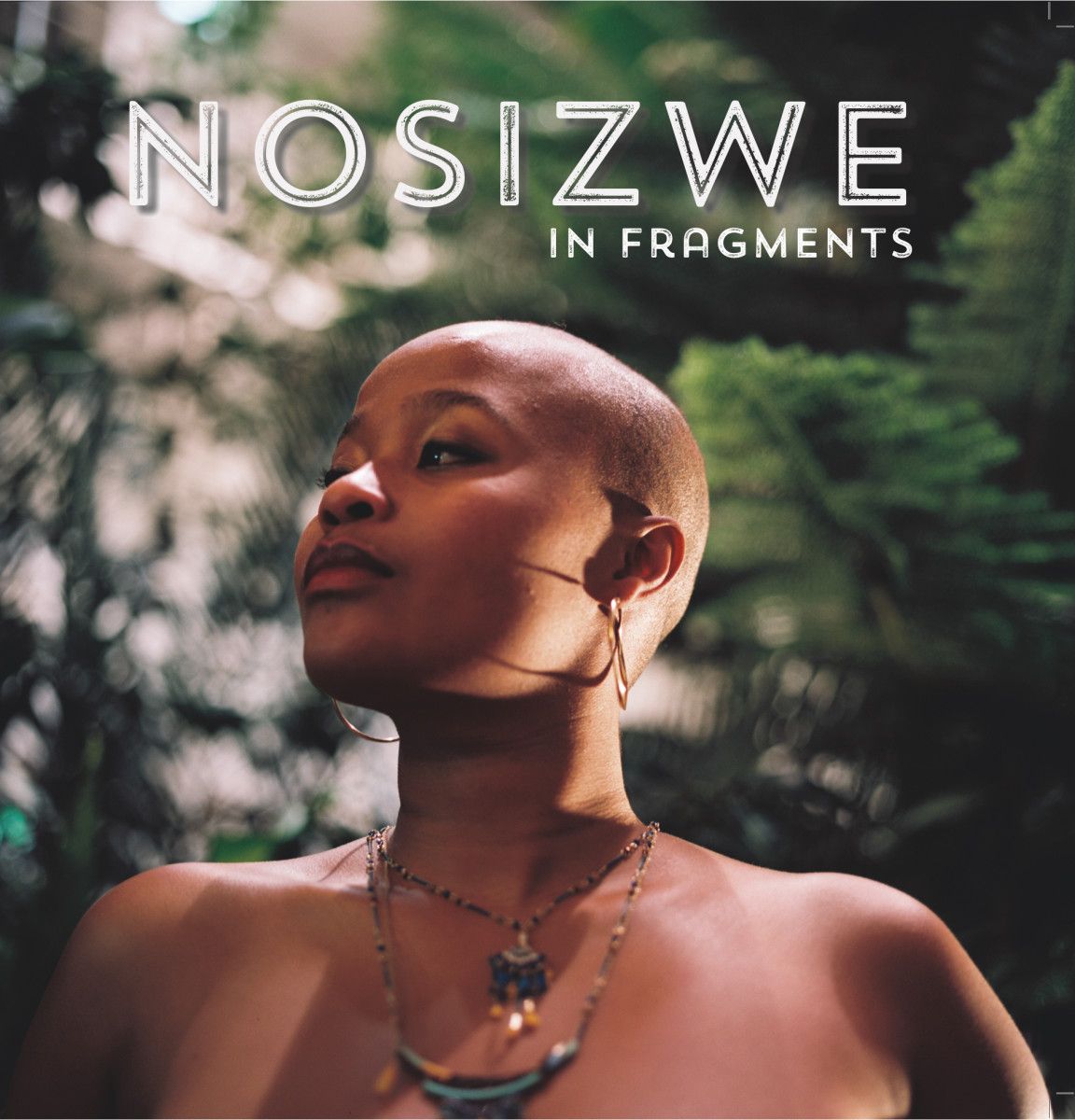

She’s vocal, yet fair on these issues and obviously very conscious of what’s going on in South Africa, and when I ask how much these issues inform her music she offers an example from “In Fragments”, the song Breathe, which she “wrote and dedicated to the student uprising.” The visual accompaniment to the single, a picture of two boys running away from a smoke grenade, which removed out of context looks like two younger men dancing, which Nosizwe brings back to the reality of the situation through her lyrics for Breathe. “I can’t breathe, I can’t see the sun for the light of day”, does not talk of a joyous occasion and after really studying the picture everything falls into its perspective. But as much as that song is about the student uprising, something that “deeply impacted” the artist, it also works in the context of American politics: “That song was definitely a reflection of the politics of SA, but also the United States with all the cop killings and the black lives matter movement.” Political issues are also moments of hope and encouragement for the artist, translated into acknowledgement and a deep seated respect in her music as inspired by the people of South Africa. “Hiya” from the album speaks of feminism and spirituality, not as a “pseudo philosophical” construct, but as a message of an openness that reflects an ingrained history between the people and the earth in South Africa and in the subtext it’s about empowerment. That “song was a thank you to my deeply spiritual and hippy sisterhood” explains Nosizwe. It is a “completely different access and entry to spirituality” for the singer and one that makes it “totally acceptable that you can acknowledge the ancestors on Saturday, go to church on Sunday and smoke weed on top of Devil’s peak on Sunday” with no contradiction between those spiritual elements, much like her album pieces together different, often contrasting things to make a whole.

She’s vocal, yet fair on these issues and obviously very conscious of what’s going on in South Africa, and when I ask how much these issues inform her music she offers an example from “In Fragments”, the song Breathe, which she “wrote and dedicated to the student uprising.” The visual accompaniment to the single, a picture of two boys running away from a smoke grenade, which removed out of context looks like two younger men dancing, which Nosizwe brings back to the reality of the situation through her lyrics for Breathe. “I can’t breathe, I can’t see the sun for the light of day”, does not talk of a joyous occasion and after really studying the picture everything falls into its perspective. But as much as that song is about the student uprising, something that “deeply impacted” the artist, it also works in the context of American politics: “That song was definitely a reflection of the politics of SA, but also the United States with all the cop killings and the black lives matter movement.” Political issues are also moments of hope and encouragement for the artist, translated into acknowledgement and a deep seated respect in her music as inspired by the people of South Africa. “Hiya” from the album speaks of feminism and spirituality, not as a “pseudo philosophical” construct, but as a message of an openness that reflects an ingrained history between the people and the earth in South Africa and in the subtext it’s about empowerment. That “song was a thank you to my deeply spiritual and hippy sisterhood” explains Nosizwe. It is a “completely different access and entry to spirituality” for the singer and one that makes it “totally acceptable that you can acknowledge the ancestors on Saturday, go to church on Sunday and smoke weed on top of Devil’s peak on Sunday” with no contradiction between those spiritual elements, much like her album pieces together different, often contrasting things to make a whole.

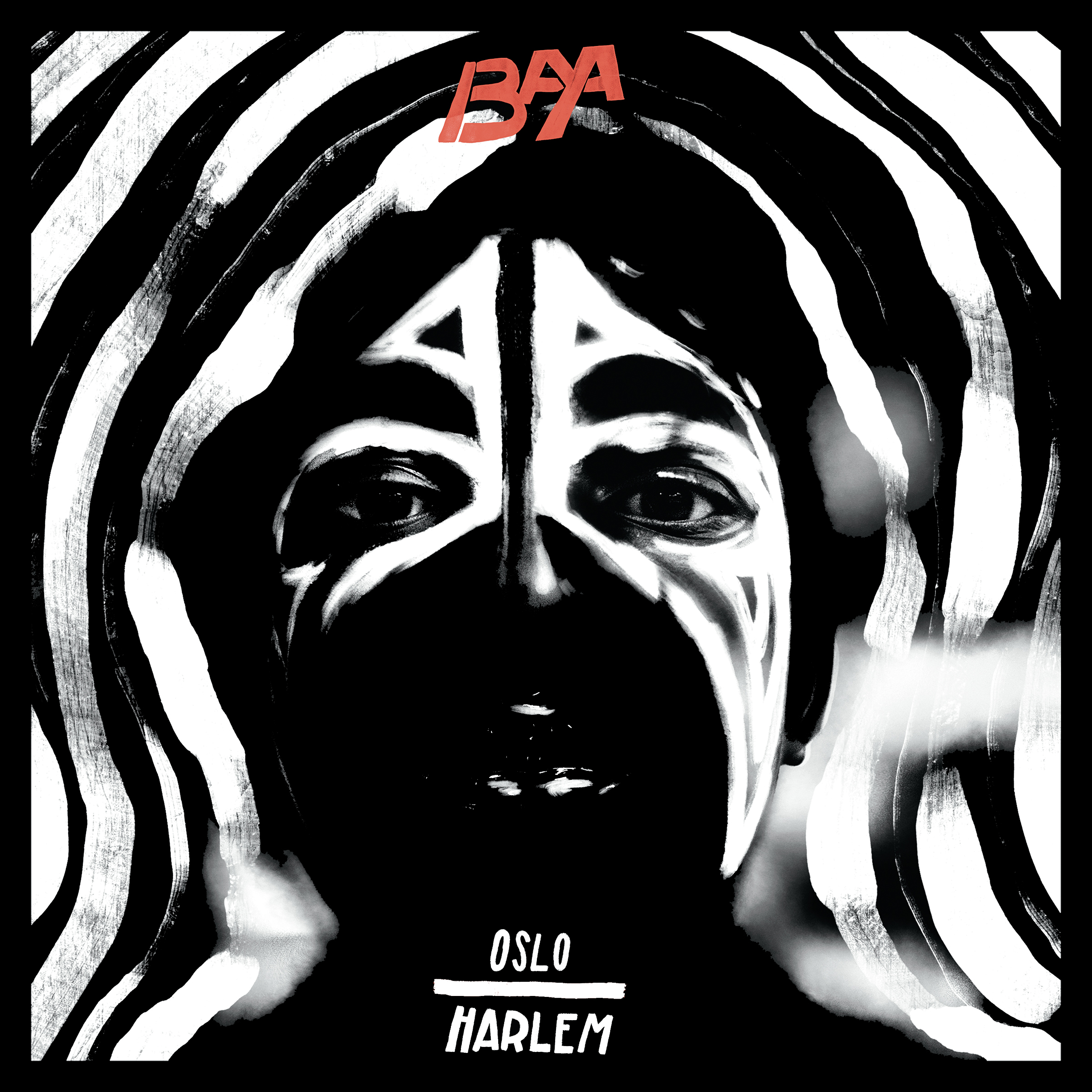

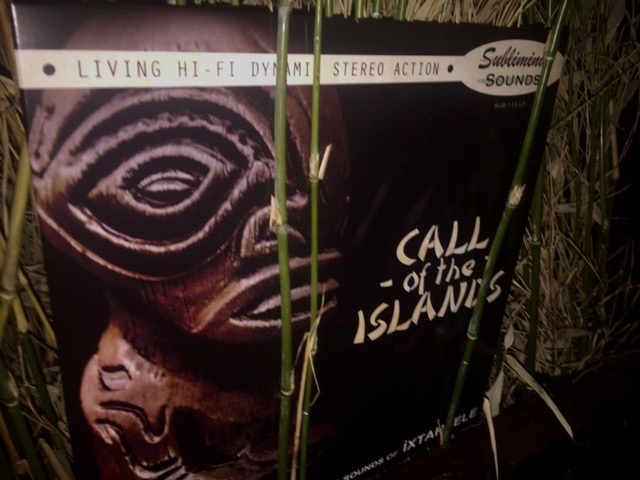

A talented young artist from the Ivory Coast, Mr. Sompohi found himself in Rome and then Bergen on scholarships to study sculpture in the eighties. It was in Norway where he would have the significant encounter with Caroline Baardsen that brought Andrew into the world, but it’s also here where he expounded on his lifelong work; delving into the concepts of the African mask through a thoroughly western image.“He found the African mask at Sagene kirke”, explains Andrew, “where he saw the mask in the church door, and he saw the parallel between the African mask and western society.” He calls the concept Gla, shortened from Glalogy. “Gla is the manifestation of the African spirit tradition, African society”, explains Mr. Sompohi during an interlude on Oslo-Harlem, his voice a rich mixture of French accentuation and a booming African tenor. “Gla is the music, Gla is the fine art, Gla is the everything” and the artist focuses all these elements through the aesthetic of the African mask. Visually, the results are striking works of immense proportions with concepts that go deeper and deeper with each idea revealing the next in conceptually dense works of art with the mask as foreground. “There’s always something” says Andrew of his father’s work, work that’s consumed “45 years” of the artist’s life, which Andrew feels he has barely scratched the surface of.

A talented young artist from the Ivory Coast, Mr. Sompohi found himself in Rome and then Bergen on scholarships to study sculpture in the eighties. It was in Norway where he would have the significant encounter with Caroline Baardsen that brought Andrew into the world, but it’s also here where he expounded on his lifelong work; delving into the concepts of the African mask through a thoroughly western image.“He found the African mask at Sagene kirke”, explains Andrew, “where he saw the mask in the church door, and he saw the parallel between the African mask and western society.” He calls the concept Gla, shortened from Glalogy. “Gla is the manifestation of the African spirit tradition, African society”, explains Mr. Sompohi during an interlude on Oslo-Harlem, his voice a rich mixture of French accentuation and a booming African tenor. “Gla is the music, Gla is the fine art, Gla is the everything” and the artist focuses all these elements through the aesthetic of the African mask. Visually, the results are striking works of immense proportions with concepts that go deeper and deeper with each idea revealing the next in conceptually dense works of art with the mask as foreground. “There’s always something” says Andrew of his father’s work, work that’s consumed “45 years” of the artist’s life, which Andrew feels he has barely scratched the surface of.

Like Mr. Sompohi’s work that finds this parallel between western society and the African mask, Baya’s music draws parallels between various aspects of music and of course the theme of the mask through Oslo-Harlem. “I’m excited for this record to have this face” says Andrew of this visual element to the album. It will also be a theme running through the live shows I learn, as Andrew collaborated with his father and Red Bull to create masks that will form the backdrop to the stage, an experience Andrew quite “inspiring”. “It was like going to art school for a week.”

Like Mr. Sompohi’s work that finds this parallel between western society and the African mask, Baya’s music draws parallels between various aspects of music and of course the theme of the mask through Oslo-Harlem. “I’m excited for this record to have this face” says Andrew of this visual element to the album. It will also be a theme running through the live shows I learn, as Andrew collaborated with his father and Red Bull to create masks that will form the backdrop to the stage, an experience Andrew quite “inspiring”. “It was like going to art school for a week.”

Oath is a very inconspicuous hole in the wall for the business district just shy of the centre of Shibuya. Inconspicuous in aesthetic, its entrance lies in a back street, but where traffic noise and very little else persist, Oath can be heard, long before it can be seen. It dominates (both physically and sonically) Tunnel, the more commercially aligned, Disco-orientated sister club in the basement. Walking through the plastic curtain over its threshold, Oath perpetuates the idiom “big things come in small packages”. A clunky iron-red look commands the interior, conservatively perpetuating the intimacy of its physical dimensions, trying very hard to contain the larger than life sound radiating through the walls, while mirrors play visual tricks to enlarge the actual size of the space. It’s barely gone ten in the evening and already a small dance floor has formed, DJ U-T representing Seltica is presiding over a small audience made up of a mixture of expats and locals. The swell from the single Tannoy® sub at my feet is loud but warm, never consuming nor overwhelming and although it’s a PA system rather than a hi-fi system, the sound in the small venue is incredibly controlled. DJ U-T plays a selection of Deep cuts that border on the malignant and darker sound of Techno eluding to more than what House percussive arrangement might suggest. The DJ stands behind the bar, where the relationship between the DJ and his/her audience is very much one of facilitator and not their nucleus of focus. Assuming the same position as that of a barman, any notion of performance is acutely missing, a universal reality I have found throughout Tokyo.

Oath is a very inconspicuous hole in the wall for the business district just shy of the centre of Shibuya. Inconspicuous in aesthetic, its entrance lies in a back street, but where traffic noise and very little else persist, Oath can be heard, long before it can be seen. It dominates (both physically and sonically) Tunnel, the more commercially aligned, Disco-orientated sister club in the basement. Walking through the plastic curtain over its threshold, Oath perpetuates the idiom “big things come in small packages”. A clunky iron-red look commands the interior, conservatively perpetuating the intimacy of its physical dimensions, trying very hard to contain the larger than life sound radiating through the walls, while mirrors play visual tricks to enlarge the actual size of the space. It’s barely gone ten in the evening and already a small dance floor has formed, DJ U-T representing Seltica is presiding over a small audience made up of a mixture of expats and locals. The swell from the single Tannoy® sub at my feet is loud but warm, never consuming nor overwhelming and although it’s a PA system rather than a hi-fi system, the sound in the small venue is incredibly controlled. DJ U-T plays a selection of Deep cuts that border on the malignant and darker sound of Techno eluding to more than what House percussive arrangement might suggest. The DJ stands behind the bar, where the relationship between the DJ and his/her audience is very much one of facilitator and not their nucleus of focus. Assuming the same position as that of a barman, any notion of performance is acutely missing, a universal reality I have found throughout Tokyo.  Inspired by Nobu’s set and recent releases by a latent Japanese Techno talent ENA, I make my way to Technique a few days later looking for some new music records. Unlike SAYA and her peers, I am here solely for new Japanese artists, but a hearty Detroit section leaves me inclined to paw around in the compact space of the record store and stick a Rhythim is Rhythim release in my bag. Back on track however and with some help from the clerk, who hands me a formidable bundle of personal picks, I make my way to a listening station looking for something that jumps out at me and my personal tastes. The man next to me is bobbing his head to Robin C and Omar V’s Full Pupp split, but my bundle is solely made up of Japanese artists and labels. Immediately, titles from Britta, Gonno and Iori jump out at me, and I can’t help but fall for the latter’s second cut, “Ripple” on Less is Techno’s ( a new French label) second only release. I flip past some other familiar titles and what I come across for the most part is a sound that is reminiscent of U-T’s set from OATH. It’s a Deep House sound for the most part, extorted to its bare essentials, loitering in the melancholy fringes of Techno. A peculiar antithesis to the more upbeat, cut & paste sound of Deep House in Europe at the moment, the Japanese interpretation, seems more inclined to follow the production aesthetics of Techno, devoid of the sample-based formula distilled from producers coming from a Hip-Hop background, with machines creating new luscious landscapes from unidentified sources. I grab a melodious deep two-tracker from EFDRSD, an outlier example of this sound, featuring an Inner Science track on the B-side that entwines you in its sweet melodic prose like an artificial intelligence learning to communicate for the first time.

Inspired by Nobu’s set and recent releases by a latent Japanese Techno talent ENA, I make my way to Technique a few days later looking for some new music records. Unlike SAYA and her peers, I am here solely for new Japanese artists, but a hearty Detroit section leaves me inclined to paw around in the compact space of the record store and stick a Rhythim is Rhythim release in my bag. Back on track however and with some help from the clerk, who hands me a formidable bundle of personal picks, I make my way to a listening station looking for something that jumps out at me and my personal tastes. The man next to me is bobbing his head to Robin C and Omar V’s Full Pupp split, but my bundle is solely made up of Japanese artists and labels. Immediately, titles from Britta, Gonno and Iori jump out at me, and I can’t help but fall for the latter’s second cut, “Ripple” on Less is Techno’s ( a new French label) second only release. I flip past some other familiar titles and what I come across for the most part is a sound that is reminiscent of U-T’s set from OATH. It’s a Deep House sound for the most part, extorted to its bare essentials, loitering in the melancholy fringes of Techno. A peculiar antithesis to the more upbeat, cut & paste sound of Deep House in Europe at the moment, the Japanese interpretation, seems more inclined to follow the production aesthetics of Techno, devoid of the sample-based formula distilled from producers coming from a Hip-Hop background, with machines creating new luscious landscapes from unidentified sources. I grab a melodious deep two-tracker from EFDRSD, an outlier example of this sound, featuring an Inner Science track on the B-side that entwines you in its sweet melodic prose like an artificial intelligence learning to communicate for the first time.

Funny story: I once stayed at that Hilton when I missed a connecting flight, and with 5 hours to spare I thought it pertinent to go clubbing. With live at Robert Johnson still fairly unknown back then and cocoon on the other side of the country, I thought I’d ask the concierge for advice, which naturally led me to a vacuous Hard House club in the city centre, spitting me back into 1997. The lesson there is, never ask a concierge for clubbing tips. But I digress, back to Phillip Lauer and Frankfurt. Yes, Frankfurt is home to the Sven Väth-designed Coccon, and ATA’s Robert Johnson, two very significant players in club music today, albeit from very different perspectives.

Funny story: I once stayed at that Hilton when I missed a connecting flight, and with 5 hours to spare I thought it pertinent to go clubbing. With live at Robert Johnson still fairly unknown back then and cocoon on the other side of the country, I thought I’d ask the concierge for advice, which naturally led me to a vacuous Hard House club in the city centre, spitting me back into 1997. The lesson there is, never ask a concierge for clubbing tips. But I digress, back to Phillip Lauer and Frankfurt. Yes, Frankfurt is home to the Sven Väth-designed Coccon, and ATA’s Robert Johnson, two very significant players in club music today, albeit from very different perspectives.

JS:

JS: Amazing! I can picture just the two of you doing the vocalist headset nod producer thumbs up music video thing that I reckon everyone was doing back then. hehe.. Wish i was there!! And to be honest my biggest dream has always been to roll down the streets of Manhattan in 1981, wearing nothing but rollerskates and a ghettoblaster…. well well, i had my own style in Oslo back then.